When it comes to building more flood-proof U.S. cities, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is, there’s plenty of federal funding available to build new infrastructure like storm drains. The bad news is, cities say they can’t make these plans without accurate federal rainfall data – records which, in some cases, are half a century out of date.

Much of the urgency around flood resilience is based on climate change: One report from the Northeast Regional Climate Center found that “100-year” storm events could be as much as 50 percent rainier by the end of the century. Recent major rainfall events like Hurricane Ida, which killed 56 people and caused $95 billion in damages across the Northeast last year, are making it clear that 100-year and 500-year storm events are no longer taking centuries to happen.

In light of these changing rainfall dynamics, wastewater managers in many cities are struggling to figure out how to upgrade local infrastructure. In the U.S., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s, or NOAA’s precipitation frequency data is supposed to tell everyone from city managers to average people how often a certain amount of precipitation is likely to fall. This information is especially critical to municipalities as they design flood-resilient sewage systems, green spaces, and even roads. As Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, told NPR, this data is “core to probably hundreds or thousands of development decisions everyday.”

Unfortunately, NOAA’s precipitation frequency data is quite outdated – as much as 50 years in some states, according to NPR. That’s not all that surprising considering that regularly updating this information is something of a herculean task for the federal agency. The maps and figures produced by the precipitation frequency data are dependent on a series of precipitation reports, known as Atlas 14.

These reports intake data (often in inches of rainfall) from weather stations throughout a state or region. These weather stations, however, are not always owned or operated by NOAA. Many stations are operated by state, local, and other federal agencies. In order to generate one Atlas 14 report, NOAA has to go through the time-consuming — and costly — process of collecting data from all of these sources.

Additionally, not every weather station feeding into Atlas 14 records precipitation data the same way or over the same time period. Some stations record total precipitation daily. Other stations might take records every 15 minutes. Some stations may have been active for 75 years, while others have been active for 20 years. For example, an Atlas 14 report for Northeastern states was the product of 7,629 weather stations, managed by 23 different agencies. This standardization and analysis process produces reports that are hardly skimmable — each one can be over 250 pages long.

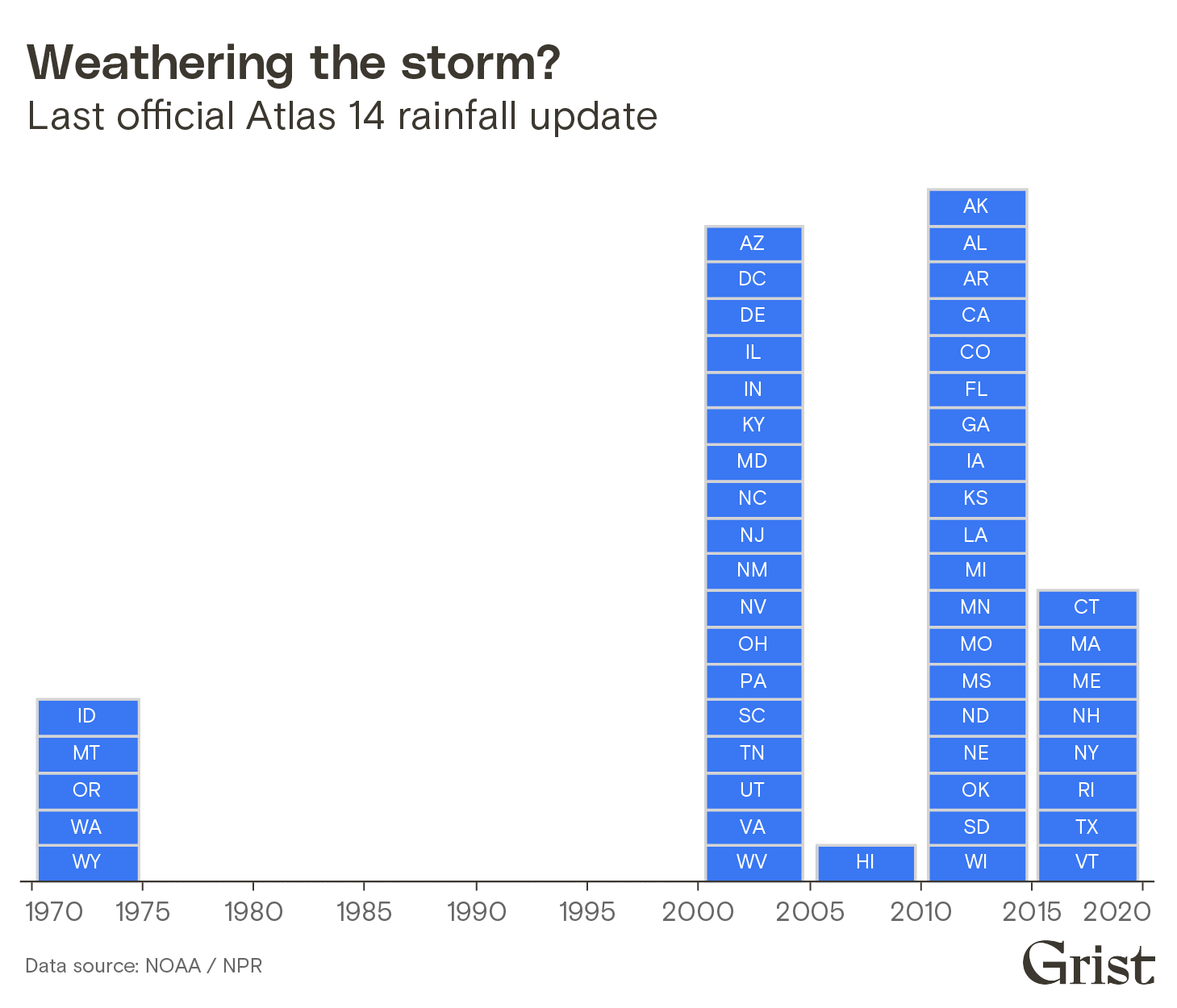

Due to these logistical hurdles, NOAA only updates Atlas 14 reports when states request and pay for them. As the chart below shows, data modernization is uneven. Northeastern states have precipitation frequency data updated within the last five years, while the Pacific Northwest is using data from the 1970s.

In response to NPR’s story about NOAA’s outdated rainfall data, the agency itself acknowledged that the staggered data update approach is far from ideal.

“It would be much more efficient to do the whole country all at once,” Mark Glaudemans, director of NOAA’s Geo-Intelligence Division, told NPR.

It’s possible that funding from last year’s $2 trillion infrastructure bill could go toward Atlas 14 modernization – and thus update rainfall projections. The bill calls for updates to precipitation data generally, but NOAA has yet to confirm whether Atlas 14 will be included.

In the absence of these updated reports, however, many cities have begun partnering with local universities to do precipitation modeling. The University of Washington’s Climate Impact Group developed an online resource that the cities of Portland and Seattle have used to upgrade their stormwater infrastructure for more extreme flooding. However, this model is only feasible in larger cities with connections to large university systems.

“Rural and smaller communities simply don’t have the resources and typically access to technology to make those estimates,” Berginnis told NPR.