Little Village, streets tightly clenched with two-flats and bodegas, is one of Chicago’s most densely populated neighborhoods. Residents call it the “Mexico of the Midwest,” as it serves as an entry port for Mexican immigrants. While there are large parks on the fringes of Little Village, there are few within the community. It is one of the city’s many “park deserts.” Streets, alleys, and parking lots have long served as makeshift playgrounds, the only green being weeds springing from cracks, or the rare lawn.

For three decades, residents begged for a verdant space where their children might play or where they could sit for a brief reprieve. Finally, weary of waiting for the Chicago Park District to cobble together such a site, they chose to do it themselves.

At month’s end, ground will be broken for Jardincito (Little Garden), a nature park for children on what was once a derelict lot. Owned and protected by the nonprofit land trust NeighborSpace, the 75-by-125-foot park will echo the design and philosophy of early 20th century landscape designer Jens Jensen, who tried to recreate the disappearing Illinois prairie inside the city, by planting native flowers, trees, and shrubs, creating ponds and rivers as well as council rings and natural performance spaces.

“This is for the 8-year-and-under-crowd and is the way of the future,” says Ben Helphand, executive director of NeighborSpace. We will, he’s certain, see more parks akin to Jardincito, designed to reunite children with nature, with hills to roll down and leafy tunnels to explore — “where they can learn to walk on a path and not asphalt.”

Rendering of Jardincito in Little VillageNeighborSpace

Jardincito is just one small piece of a massive regreening underway in Chicago that’s being driven by both community groups and government leaders. City officials want Chicago, already celebrated for its architecture, to be recognized as a city of world-class landscape architecture as well. Chicago is home to 570 parks, of which a quarter are historic landmarks, designed by the likes of Jensen, Frederick Law Olmsted, and William LeBaron Jenney.

“We are the richest city in the world in terms of park facilities, amenities, and resources,” says Julia Bachrach, historian for the Chicago Park District. “It’s an embarrassment of riches. Living near Jensen’s Columbus or Humbolt parks is like having a Mona Lisa in your back yard.”

But as the story in Little Village shows, not all neighborhoods have benefited from those riches. Now, though, the parks movement hopes to correct that, making up for the wrongs created by racism, rapid growth, and for negligence in the early 1980s. That’s when the U.S. Department of Justice sued the Chicago Park District for discrimination in its allocation of recreational and park services, neglecting parks in both Hispanic and black neighborhoods. Improving and creating parks, city officials say, will slash crime rates, offer youth recreational opportunities, and instill neighborhood pride.

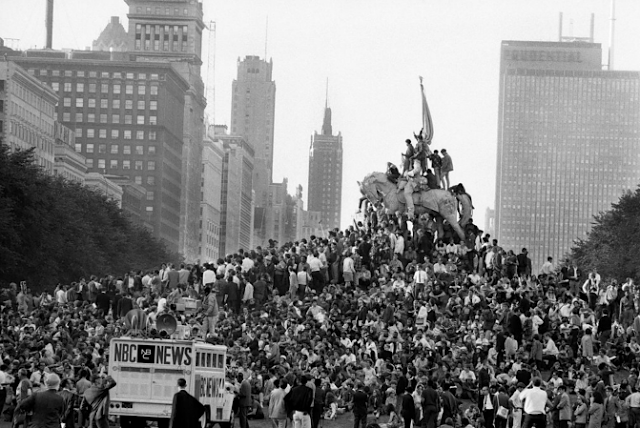

Demonstrators on the fringe of Grant Park during the ’68 Democratic National ConventionChicago Historical Society

Nationally, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, stories on the death of our parks were rampant. In Chicago, Lincoln and Grant parks conjured up images of demonstrations against the Vietnam War and the riots “The Whole World is Watching” during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

But Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring awakening the environmental movement and the emergence of Earth Day later led to a flurry of park advocacy groups such as Chicago’s Friends of the Parks. These groups shone a spotlight on years of park neglect, not only in upkeep, but in who had access to parks — and the poor black and Hispanic neighborhoods that had long been forgotten.

Resurrection of parks in the Windy City began with a force under former Mayor Richard M. Daley, who began to undo damage wrought by his father when he was mayor. After many visits to Europe, Daley sought to bring back the city’s boulevards, filling them with islands of blooming flowers and trees like those in Paris. Daley helped set plans in motion for improving lakefront greenspace, cleaning up the Chicago River, and building a riverwalk. His shining moments included seeing Millennium Park open to the public in 2004.

Early efforts at restoring parks were not always successful, however. Hasty upgrades blurred gang boundaries, especially along Chicago’s West Side, many of which divide land in a city park where the only mutual territory might be a bridge. In 2011, the situation was still bad enough that the Chicago Tribune ran an article headlined “Cramped Chicago: Half of the city’s 2.9 million residents live in park-poor areas.”

These days, before altering or creating a park, the city spends a significant amount of time gathering community input, says Rob Rejman, director of planning and construction for the park district. “Needs shift by block,” he says.

Aerial rendering of the 606, opening this springTrust for Public Land

The city’s park boom has escalated under Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who wants to have a park within 10 minutes walking distance of every resident’s home, and two acres of parkland per 1,000 residents. Under Emanuel’s Chicago Plays! Program, the city has set out to rejuvenate 500 neighborhood parks; so far, 300 have been completed.

Expansions and renovations are planned or underway at both large and small parks. Two new parks will be formally unveiled this spring: the 606 (formerly known as the Bloomingdale trail) that wends through several diverse neighborhoods, and the 20-acre Maggie Daley Park, located in the heart of the city near Millennium Park, and known for its ice skating ribbon. Daniel Burnham’s Northerly Island, a 91-acre peninsula jutting into Lake Michigan, is being turned into a multi-nature habitat.

Also in the works: The University of Chicago, on the city’s South Side, has made a bid to put the Obama Presidential Library in one of two Olmsted-designed parks: Jackson Park, festooned with lagoons and a wooded island, or Washington Park, with a large meadow and lake. A 140-acre parcel of Jackson park is already under renovation. Known as Project 120, it promotes Olmsted’s original vision for the park by adding 12 new ponds for dragonflies, amphibians, and mudpuppies, new islands, a million wildflowers, and 330,000 shrubs, plus a controversial art installation by Yoko Ono.

None, however, seem to match the beauty behind Little Village’s Jardincito. From this small, barren city lot, a host of trees and native flowers and shrubs will grow. Though miniscule compared to the lakefront giants, the park will have space for small children to run barefoot in the grass, to hear and see birds. As Jens Jensen’s designs demand, there will be wonder at every small turn.

The design was influenced by the philosophy of Roger Hart, environmental psychologist and co-director at the City University of New York’s Children’s Environments Research Group, who teaches that all children, especially the disadvantaged, must have access to nature. It will be built and planted by six local members of the nonprofit Student Conservation Association known as the “Jensen Crew” — the brainchild of Carey Lundin, who directed the film Jens Jensen The Living Green to connect his story to today’s issues — and stewarded by residents of Little Village.

NeighborSpace, along with The Student Conservation Association and the American Society of Landscape Architects, is hoping to replicate the park in other Chicago neighborhoods and expand nationally with Jensen crews who are introduced to careers in landscape architecture.

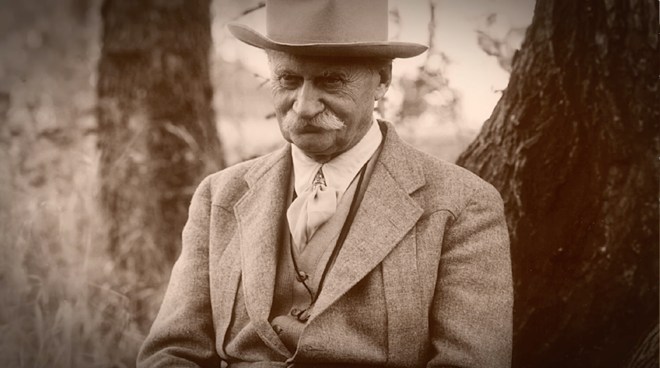

Urban parks pioneer and “poet of the prairie” Jens JensenChicago Park District

That the tiny park reflects Jensen’s vision is befitting. He, too, was an immigrant, Danish-born and working as a street sweeper and tending to the grounds of Humboldt Park before rising to be the dean of American landscape architecture in the 1930s. Like the social activist and reformer Jane Addams, Jensen was keenly aware that the city’s West Side, rife with laborers and industry, lacked the lush parks and green spaces of communities closer to Lake Michigan.

Jensen was way ahead of his time. He promoted urban farming as early as 1908, often growing large community vegetable gardens within his parks as a means to teach children about nature and feed people in the crowded tenement districts. He also proposed that vegetable and fruit gardens be grown on land surrounding factories. Considered a “poet of the prairie, maker of public parks, prophet of conservation,” he created parks and spaces as a rebuttal to the encroaching structures of industry.

Jensen understood that a neighborhood, no matter how dense or poor, needs a park filled with nature. “Trees,” he once said, “are much like human beings and enjoy each other’s company. Only a few love to be alone.”

Jens Jensen food garden in Garfield ParkChicago Park District

Want to learn more about Jensen? Early next year, PBS will air nationally the documentary Jens Jensen The Living Green by Chicago filmmakers Carey Lundin and Mark Frazel. It will be shown at the New York Botanical Garden on April 22, and the AMC Burbank Theater in L.A. on April 27. Here’s the trailer: