In 10 years, Los Angeles plans to reduce per capita water use by 22.5 percent. It will no longer get any of its electricity from coal-fired power plants. It will turn public library lawns into urban gardens and lay out rain barrels like a city full of survivalist homesteaders. In 20 years, at least half of all journeys in L.A. will be taken on foot, by bike, or by using public transit — which is another way of saying that in 20 years, Los Angeles will be San Francisco, circa right now. Though probably more glamorous.

Historically, Los Angeles has been the site of some of the U.S.’s most lavish dystopian futures (Exhibit: Blade Runner). So reading a speculative plan for the city — one which was created at the behest of Mayor Eric Garcetti, signed off on by every city manager, and released this week — makes for a surreal experience. All these years of being America’s fantasy dystopia, and Los Angeles turns out to have its own plans for the future.

Sustainability plans are something of the hot new dance craze in American cities — New York has one, Washington, D.C., has one, nearby Santa Monica has one. The terrible acronym for Los Angeles’s sustainability plan — pLAn — echoes the eccentric capitalization choices of New York’s plan (PlaNYC). But while many of these plans are superficially similar — more parks, more walking — there are huge regional differences.

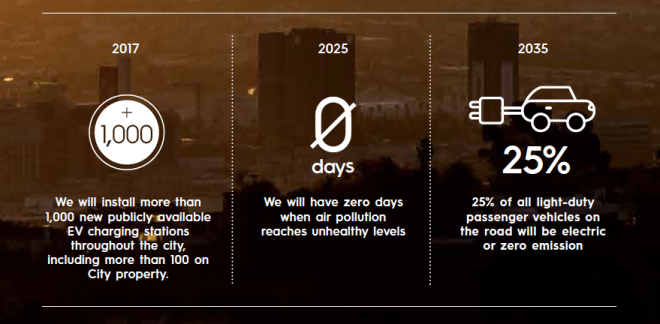

New York is an already dense urban landscape whose main priority is protecting itself from the property damage caused by storm surges. Los Angeles was a sprawling city even in the days before private cars (the L.A.’s streetcar lines actually enabled the city’s first suburbs), and it’s less at risk from storm surge than from drought. Rising temperatures from climate change will also make temperature inversion over the city, which traps air pollution near ground level, even worse.

A day before the sustainability plan was released, a group of researchers at the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA released another first: an Environmental Report Card for the County of Los Angeles, which gave the city a C+ for importing over half of its water from more than 200 miles away, for not keeping sufficient track of where its recycling and hazardous waste is going, for having groundwater tainted by aerospace-industry runoff, and for having air that is pretty hard to breathe, especially near the ports and freeways.

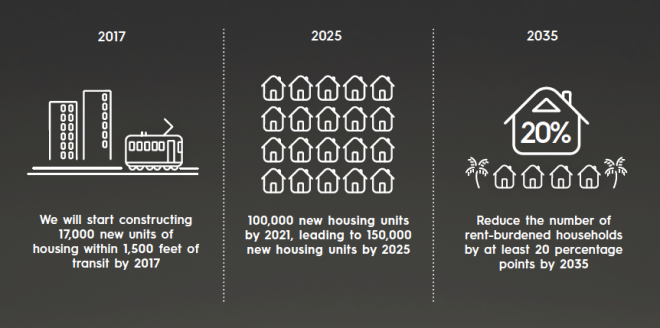

Mark Gold, the lead researcher on the report card, sees L.A.’s “pLAn” as a good sign — for one thing, it sets goals with hard numbers, percentages, dates, and timelines, instead of using vague language like “endeavor to.” Gold also approves of how the pLAn frames sustainability as a social justice issue rather than just an environmental one.

The pLAn, for example, sets out to reduce the number of annual childhood asthma-related emergency room visits to 14 per 1,000 visits in the next 10 years, and 8 per 1,000 by the next 20. Currently, in some neighborhoods the rate is more like 30 per 1,000. It also sets a goal that in the next 20 years, 75 percent of all Angelenos will live within half a mile of park or open space, and within half a mile of fresh food.

“We’re not going to be successful if there are communities that are left behind,” Gold said in a phone interview. “This is tailored to L.A. This is embracing the diversity that is L.A. -– not trying to change the character of the city. That’s the optimistic part about what the mayor is pitching. We can make a change in the environment and make it unique to Los Angeles.”

L.A.’s previous mayor, Antonio Villaraigosa, laid the framework for this idea of cutting pollution and putting in transit as the kind of economic and public health issue that cut across lines of class and race. Among other things, he passed a voter-approved sales tax that will fund much of the mass transit the plan needs to meet its goals — right now, construction of the city’s transit system is one of the largest public works programs in the United States.

The hardest part of the pLAn, according to Matt Petersen, chief sustainability officer for the City of Los Angeles, will be water. Los Angeles expects to add another 500,000 residents over the next 20 years, and it doesn’t even have enough water for the amount its current residents use.

The city has already changed its definition of “local water” so that water pulled in from the Owens Valley, 200 miles away, no longer counts. Instead, L.A. is trying to clean up the San Fernando Basin, which was polluted by the aerospace industry, so that water can be added to the city’s water supply. But, Petersen adds, dealing with water has an easy side, too — because it’s about changing people, instead of infrastructure or technology, and people are spooked by the drought.

“We use 50 percent of our water for outdoor landscaping,” Petersen said. “The green lawn, the car, and the swimming pool — that’s the dream out here. That’s going to change.”