It’s a balmy, mid-November morning in Miami Beach, Fla., and I’m sitting at one of the cafe tables in front of the local Whole Foods, sipping a cup of coffee, and watching the tide come up. Oh, you can’t see the ocean from here. The tide is gurgling up through the storm drains along the street.

It starts at about 8:00. A trickle of water from a nearby grate quickly becomes a stream which becomes a lake, spreading across the intersection of Alton Road and 10th Street. By 8:20, water pours off of the cars rolling into the parking lot. At 8:40, it reaches the axles of the Jeep parked on the corner. Pedestrians abandon the submerged sidewalks for high ground in the middle of the Alton Road, dodging rooster tails kicked up by passing vehicles. To get back across town, I’ll have to wade through murk that comes almost to my knees.

One of my sources here, a scientist studying the impacts of climate change and sea-level rise, tells me that if I stick my finger in that water and taste it, it will be salty. I look at the gunk burbling out of the gutters, swirling with oily rainbows and cigarette butts, and decide to take her word for it.

The water is coming from Biscayne Bay, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies between Miami Beach and the city of Miami. Steadily rising high tides in recent years have driven the stuff backwards through the storm drains, underneath protective seawalls, spilling into the streets and spawning a multimillion dollar retrofit to the city’s drainage system. In the process, Crockett and Tubbs’ seaside haunt has become a bellwether for coastal communities everywhere that are only just beginning to grok the implications of a problem that will dog us for generations.

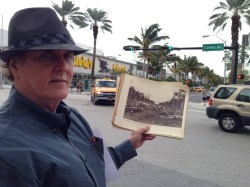

Greg HanscomBefore and after: Thorn Grafton with an archival photo of crews bulldozing Miami Beach. Click to embiggen.

To get a sense for what’s at stake in Miami Beach, I talked to Miami architect and preservationist Thorn Grafton. His great-great-grandfather came here to grow fruit, and helped build the first bridge between the island and the mainland, paving the way for the island’s transformation from a mangrove swamp into a gleaming partier’s paradise. Grafton has photographs of the barrier island before it was bulldozed: The dunes were spiked with sabal palms, and red mangroves rose 40 feet from the shallows.

Grafton’s grandfather, who did early work in Miami Beach, was influential in creating South Florida’s unique architectural style. His father was a well-known Miami architect as well, and his mother was a prominent advocate for preserving the city’s historic buildings. After his own architectural studies in New Orleans, Grafton himself took up the cause, joining local activist Barbara Capitman in her fight to save the iconic art deco buildings of South Beach by putting the area on the National Register of Historic Places.

Capitman and her allies ultimately succeeded, although many classic buildings were lost to mega-resorts and highrises along the way. Now, however, sea-level rise could doom all that was saved.

“My concern, short term, is that a storm surge is going to hit all the historic hotels on Ocean Drive,” Grafton says, “and some of the building owners are going to use that as an opportunity to [tear down the old structures and] rebuild.” Longer term, he worries that rising seas will cut off the two low-lying causeways that currently provide access to the island.

The access issue, at least, is taken into account by the city’s 20-year Storm Water Management Master Plan, published in 2012 with the goal of protecting buildings and keeping evacuation routes open during a once-in-five-years storm. Among the first of $196 million in suggested upgrades: Retool the storm drains along Alton Road, installing “backflow preventers” — a kind of one-way valve that stops seawater from running through the system backward — and pumps that can push water out of the streets and into the bay.

“The city has been worried about storm water and sea-level rise for years and years,” Jay Fink, assistant director of the Miami Beach Public Works Department, tells me during a meeting at city hall. “With the new administration” — of Mayor Philip Levine, who was elected last year — “it’s been elevated as a priority. They’ve said we need to look at this.”

City leaders have also signed on to the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Action Plan, a four-county roadmap for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change. And a delegation from Miami Beach went to the Netherlands this fall to look at how the Dutch are dealing with rising seas. (For those looking for upsides to climate change, look no further than Dutch engineering firms, which do booming business consulting with seaside cities around the globe.)

But there are some key differences between Southeast Florida and the Netherlands, chief among them that the bedrock here is limestone, which is highly porous. Geologists compare it to Swiss cheese. Build all the dikes and seawalls you like, they say: As the seas rise, the water will just seep in through the ground. Blocking the storm drains may slow it down some, but it’s going to come regardless.

Build the seawalls high enough and the pumps big enough, and you might be able to keep the water out of the streets. But while Miami Beach’s storm water plan puts the city ahead of the curve compared to other oceanfront communities, it also shows just how limited this sort of planning can be. The study recommends raising sea walls around the island to 3.2 feet above the baseline sea level (the North American Vertical Datum of 1988, for you geography geeks), and a foot above what the Federal Emergency Management Agency has deemed the maximum “tidal stillwater” elevation. That’s a normal high tide, sans waves. To put that into perspective, Hurricane Andrew, which narrowly missed Miami Beach in 1992, kicked up storm tides of almost 17 feet.

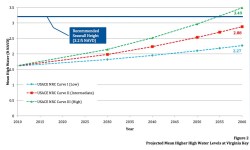

Set aside the possibility of a catastrophic storm for a minute, and consider that the plan is based on protecting the island against approximately eight inches of additional sea-level rise — the intermediate scenario envisioned for 2030 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Follow the Army Corps’s graphs out to 2060, and even the low scenario projects more than two feet of rise. The high scenario puts the seas three-and-a-half feet above the baseline, topping those newfangled seawalls and submerging most of the island.

City officials already realize that their initial calculations may have been too low. “I’m not naive enough to think we’re going to solve the greenhouse gas issue tomorrow,” says Miami Beach City Manager Jimmy Morales. “The reality is that we need to figure out how to deal with this water. Can you protect historic properties? Are there areas that need to be raised and fortified? Are there areas of this city that need to be abandoned because they’re too difficult to keep dry?”

Morales has ordered his staff to revisit the storm water plan, and start exploring these other questions as well. They have their work cut out for them: At present, local zoning and building codes don’t even take sea-level rise into account.

Some short- to medium-term fixes are emerging, however. The city is using natural defenses such as reinforced dunes to protect its oceanfront, for example, and there’s talk of replanting mangroves along the west side of the island. Taking a page from the Dutch playbook, Morales says the city may install underground retention tanks to store water during storms and unusually high tides, keeping at least some of the stuff out of the streets. A grant from the Rockefeller Foundation is helping explore new ways of funding projects like these.

Grafton and other architects, meantime, are already imagining how structures can be built and redesigned to survive amid the rising tides. He envisions houses built on stilts, moving social areas to the second stories of historic hotels, even reconstructing some iconic buildings by putting more resilient and storm-hardy structures inside the old facades. With the right planning, Miami Beach could become the new Venice, navigable by boat and accessed via elevated light rail.

But while these fixes may help address Miami Beach’s problems for the next 50, even 100 years, the seas are going to keep on rising unless the rest of us get with the program. “Long-term, this is an international issue,” Morales says. “If you get 20 feet of sea level rise, it’s not just Miami Beach. How much of the East Coast have you lost?

“If there was a silver lining to Hurricane Sandy,” Morales continues, “it’s that areas that did not think sea-level rise and resiliency were important — including Manhattan, the financial capital of the world — woke up one morning and said, ‘This is my problem too.’”

In my next installment, I’ll explore the science of sea-level rise in, um, greater depth.