Environmental activist Sue Nissen wears a teaspoon on a string around her neck, which she likes to hand out to lawmakers during hearings in the Minnesota state legislature. That’s because one teaspoon of salt is enough to pollute five gallons of water, making it inhospitable for life.

Road crews dump more than 20 million metric tons of salt on U.S. roads each winter to keep them free of ice and snow – an almost unfathomable number of teaspoons. Now, Nissen’s organization, Stop Over Salting, is pushing for Minnesota to pass a bill to reduce that figure by helping applicators learn how to use less of it — a technique called “smart salting.”

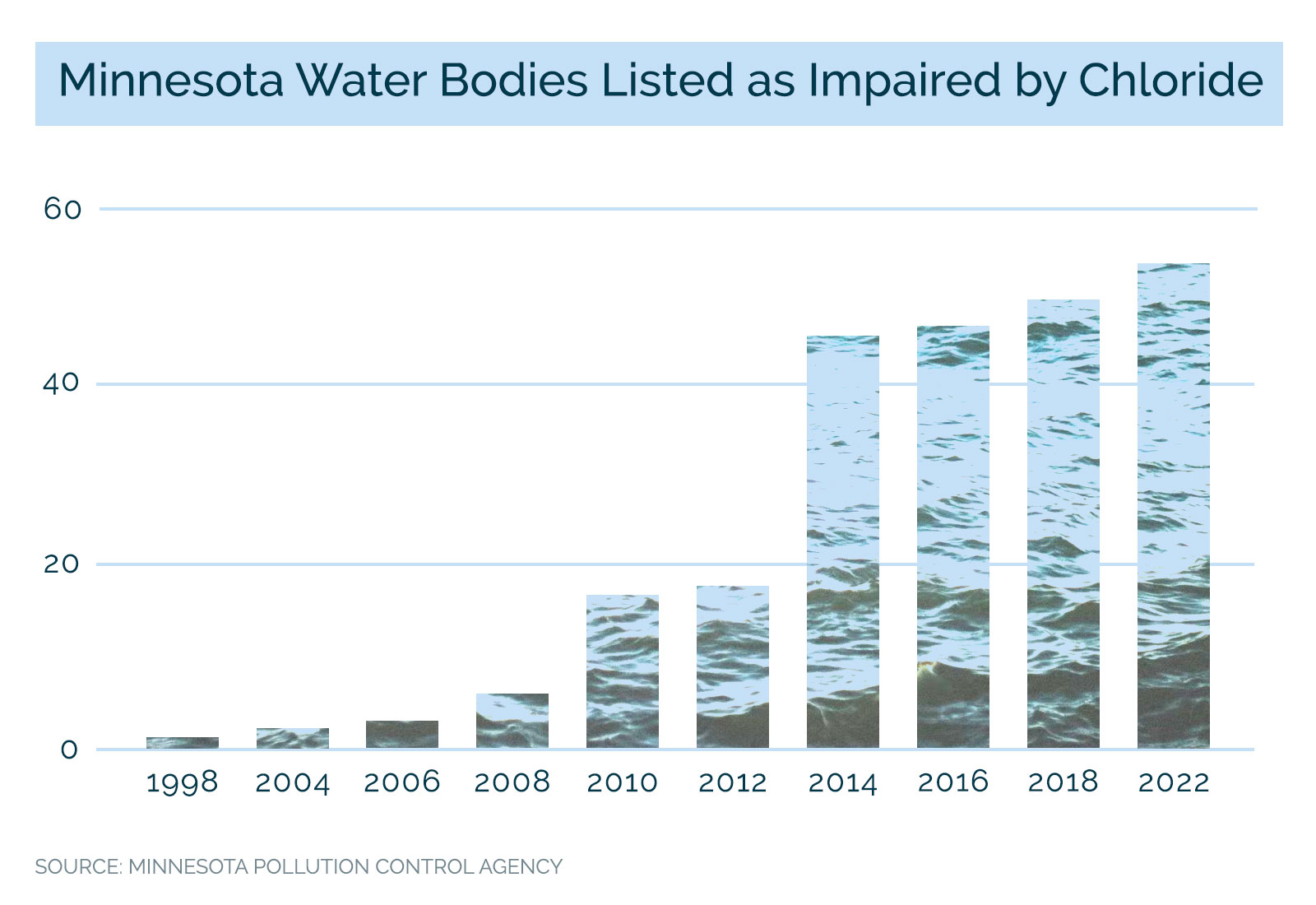

The reason, she said, is because the state’s freshwater bodies are in a crisis: 54 lakes and streams are “impaired” by high salt concentrations, meaning they fail to meet federal water quality standards, while dozens of others are drawing closer to that tipping point, according to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. But environmental activists and scientists argue that it’s possible to maintain winter safety while reducing the amount of salt spread on streets and highways.

“There are solutions,” Nissen told Grist. “We can still have our winter mobility and be safe … with less salt.”

Road salt, which works by lowering the melting point of ice, is cheap and effective, reducing car accidents by up to 85 percent. But aside from corroding metal and concrete — leading to an estimated $5 billion worth of damages each year — it also ends up in rivers and lakes, where it has toxic effects on aquatic life. In January, researchers from the United States and Canada found that even salt concentrations below the threshold considered “safe” by governments were causing severe damage to organisms.

Warnings about the effects of road salt on freshwater bodies and ecosystems first started in the 1970s, said Bill Hintz, the study’s lead author and an environmental scientist at the University of Toledo in Ohio. But salt use has tripled since then. Now, with climate change encouraging excessive salting by making winter storms more unpredictable, officials in states like Minnesota are starting to realize the magnitude of the problem.

The Minnesota bill, if it passes, would be one of the first state laws to encourage “smart salting,” a way to reduce road salt use while still maintaining winter safety. New Hampshire passed a similar law in 2013, while Wisconsin also has a “salt wise” training program. In New York, the Adirondack Road Salt Reduction Task Force launched a three-year pilot program this month to reduce freshwater salt contamination.

The concept of smart salting encompasses a range of technologies and techniques. Brining involves laying down a liquid mixture of salt before a storm, which prevents ice from sticking and reduces the need for repetitive salting. It also includes applicators learning how to calibrate their equipment to know how much salt they’re using in the first place, as well as when to stop salting (below 15 degrees Fahrenheit, for example, salt is much less effective). Minnesota has been training applicators in these techniques since 2005, but under the new bill, certified “smart salters” would be protected from liability, preventing them from being sued for slip-and-fall accidents.

Nissen hopes that this protection will encourage more private applicators to be certified in smart salting practices, which are not only better for the environment but help save money on salt. But convincing them is a challenge, she said, because people have come to associate the sight of salt with winter safety. “If anybody calls in and says, ‘I don’t see enough salt,’” she said, “they call the applicator and say ‘get out there and put more salt down.’”

This overreliance on road salt has severe environmental consequences. The most common kind used for de-icing is sodium chloride — rock salt — but calcium and magnesium chlorides are sometimes used for colder weather. Once it enters a body of water, salt is almost impossible to remove, requiring expensive and energy-intensive processes like reverse osmosis. Chloride, in particular, binds tightly to water molecules, and can be highly toxic to organisms like fish, amphibians, and microscopic zooplankton, which form the basis of the food chain in a lake or river.

If the zooplankton die off, Hintz said, it can trigger a chain reaction that allows algae to flourish, causing toxic blooms and affecting native fish species that can’t survive in murky waters. That should trouble recreational fishers everywhere, he said, but salt contamination has also made it into drinking water, particularly in areas where people rely on deep wells to reach groundwater. In the Adirondacks in upstate New York, a 2019 study found that 64 percent of wells tested for sodium exceeded federal limits — which can be particularly dangerous for people with high blood pressure or others on sodium-restricted diets.

This makes salt-reduction programs like Minnesota’s crucial, Hintz said, to “flatten the curve” of freshwater salt concentrations. “Best management practices are critically important right now,” Hintz said.

But reducing salt use will only slow down the crisis, not stop it, Hintz warned. Salt that’s already been deposited might take years to show up in groundwater, and how much can be “safely” added without permanently damaging an ecosystem is an “open question,” he said. And non-salt alternatives, like sand or even beet juice, can come with their own problems, silting up rivers or introducing nutrients into ecosystems that can lead to algal blooms.

Some cities have opted for proactive solutions — preventing snow and ice from building up in the first place, rather than melting it with salt once it’s already a problem. Since 1988, the town of Holland, Michigan, has invested in a “snowmelt” system, which uses pre-heated water from a nearby power plant to warm sidewalks and roads through a network of pipes underneath the surface, eliminating the need for salting. But solutions like this one are expensive and labor-intensive, said Amy Sasamoto, an official with the city’s downtown development district. The town spent over $1 million to install the first 250,000 square feet of underground tubing, and the system still only encompasses a few streets in Holland’s main downtown shopping area, although Sasamoto said it could expand along with future development.

These solutions may not be scalable to something like a four-lane highway, said Xianming Shi, an engineer and the director of the National Center for Transportation Infrastructure Durability & Life-Extension at Washington State University. Shi studies how “connected infrastructure,” such as cars tapped into an information-sharing network, can increase winter road safety. For example, sharing real-time information about road conditions can help road maintenance crews know how much salt to use, reducing oversalting.

But even improved technology and data-sharing won’t be enough, Shi said, to stop the flow of salt. Instead, it’s going to be crucial to encourage safer winter driving habits — like asking people to stay home during storms whenever possible, or to drive more slowly even on a highway.

“People’s mindset is more of this moment, like ‘I want to drive fast through the winter,’” Shi said. “They don’t realize that this has a hidden consequence.”