This post was originally published on Dec. 16, 2014, and is being republished now as part of our Seattle series. Unfortunately, the megaproject fustercluck hasn’t improved in the last six months — it’s only gotten worse.

—

Last week, I mentioned in passing that Seattle is in the midst of a full-spectrum transportation fustercluck. It has since come to my attention that some Grist readers are unfamiliar with the fustercluck in question, even though it recently made The New York Times and NPR.

This cries out for remedy. A tragicomic infrastructure own goal like this deserves wider exposure. Perhaps some lessons can be learned. Or you can just point and laugh.

“Ha ha, Seattle,” you can say. “What a fustercluck.”

—

We are currently at a crucial decision point in the story. There’s still time for Seattle leaders to change course, though it looks unlikely. But first, some history.

The epic tale begins with the Alaskan Way Viaduct, a two-tiered, elevated section of State Highway 99 that runs right through downtown along the city’s waterfront, providing a spectacular view of the skyline and Puget Sound.

The Alaskan Way Viaduct slices through Seattle.WSDOT

There are two problems with the viaduct.

One, it was a stupid idea in the first place, one of the many stupid decisions made during the highway-building frenzy of the ’50s. It went wildly over budget, didn’t solve any of the traffic problems it was supposed to solve, and worst of all, cut Seattle off from its gorgeous waterfront.

To get from the downtown core to the adjacent waterfront, pedestrians have to walk through a gloomy, shaded area beneath the highway, which, because it’s gloomy and shaded, has been given over to parking lots, a waste of precious urban land. This has left the waterfront isolated, a tourist destination rather than an integrated part of city life.

Second, the highway is on the verge of falling down. In 2001, the Nisqually earthquake damaged it, leading to $14.5 million in emergency repairs. Since then, the viaduct has been “settling,” i.e., sinking and cracking. In 2007, a group of researchers from the University of Washington concluded that, for safety reasons, the viaduct needed to be shut down within four years. “It’s coming down in 2012. I’m taking it down,” then-Gov. Christine Gregoire (D) said. “That’s the timeline. I’m not going to fudge on it.”

Spoiler alert: It’s still up.

—

What to do about the viaduct? There were three basic options:

- Replace it with a new elevated highway.

- Replace it — at least the part of it that goes through the downtown core — with a giant tunnel that would be covered over to allow downtown to connect with the waterfront.

Seattle’s tunnel plan.WSDOT

- Don’t replace it with a highway at all. In its place, create a walkable waterfront with a modest four-lane street. To accommodate traffic overflow, add transit upgrades and street improvements in the surrounding area.

A cross-section of the surface/transit option.People’s Waterfront Coalition

The third, “surface/transit” option was the cheapest and most in line with smart green urbanism. Naturally, Seattle VSPs ignored it entirely.

Reporter Dominic Holden — who has covered this story better than anyone, for Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger, but has now been lost to Buzzfeed — summarized the situation thusly in 2010:

Seattle didn’t want to replace the viaduct with a tunnel. Voters rejected both a tunnel and a new elevated highway by wide margins in March 2007. A stakeholders group—people representing business and waterfront interests—convened to discuss what they wanted. Representatives from the city, county, and state transportation departments ruled out a tunnel. They elected for a smaller viaduct or a surface/transit option. A deep-bore tunnel was out of the question, in part because the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) said it was too expensive. At a closing meeting of the stakeholders group, WSDOT’s David Dye made a speech, saying, “It is out of reach in the current state of affairs to make it happen.” He added, “It would be disingenuous of me to sit here representing the state to say, ‘Geez, you know, let’s go build a deep-bore tunnel.'”

The state is now on the verge of building a deep-bore tunnel.

Heh.

Turns out most people simply can’t fathom getting rid of an urban highway. No matter how many examples to the contrary accumulate, people instinctively think that tearing down a highway means that all the same traffic will just spill onto side streets.

So, an unholy alliance — downtown business groups, large companies like Boeing (whose interest in Seattle transportation begins and ends with getting commuters through it quickly), the antediluvian WSDOT, craven Seattle City Council members, craven state legislators like Ed Murray (who sponsored the tunnel bill and is now mayor), and head cheerleader Gregoire — bullied the tunnel back onto the agenda, and Seattle voters, sick to f’ing death of arguing about it, finally voted in 2011 to allow it to go forward.

A small bit of tunnel. WSDOT

Most charming is the financial setup. Originally the state and city were each financially responsible for their part of the project — the state for the tunnel, the city for surrounding infrastructure, like the new seawall, that would be needed to make the tunnel possible. Tunnel cost overruns would be covered by the state. Back to The Stranger:

But the state screwed Seattle at the last minute. One month after signing the agreement, the legislature passed the law capping spending and requiring Seattle to pay for all cost overruns—including all cost overruns on the state’s part of what is a state highway project.

This is an unprecedented funding arrangement: city taxpayers on the hook for a state highway project.

The 2009 tunnel law passed by the City Council specifically says Seattle taxpayers will only pay the $937 million that they have already offered up. But state law says Seattle taxpayers are on the hook for overruns. Surely this is the kind of high-stakes confusion that state and city leaders would clear up before the digging began, in case the unexpected happened?

Spoiler alert: They didn’t.

—

This grim prelude led many, many people to warn, repeatedly and at great volume, that Seattle was about to get fucked. Here’s how Holden started his story on it:

You’re about to get fucked, Seattle.

Read Holden’s story for details, or my long 2010 interview with local activist Cary Moon, which comprehensively covers the reasons this thing is a bad idea.

In short: There is no plan to resolve the dispute over cost overruns, which are ubiquitous on projects like this; at $4.2 billion, it’s the most expensive transportation project in state history. The tunnel will have no exits — no ingress or egress — throughout the entire downtown core (which makes the support of downtown businesses all the more mystifying). It won’t allow transit, only cars. It will be tolled, highly enough, by the state’s own estimates, to drive nearly half its traffic onto the aforementioned side streets. It will be a precarious engineering feat, the widest deep-bore tunnel in history, digging right between a) Puget Sound and b) the oldest part of Seattle, with vulnerable buildings and God-knows-what buried infrastructure. Also: Pollution. Climate change. It’s the 21st f’ing century. On and on. People said all this and more, in real time, to no avail.

One of the people fighting hardest against the tunnel? Visionary mayor Mike McGinn, who spent his term in office warning that exactly what is happening now was going to happen. For his efforts, Seattle voted him out of office. We prefer to hang on to our illusions.

Holden’s 2010 list of things that might go wrong with the project began with these:

1. The tunnel-boring machine gets stuck

2. Our plan to deal with a broken machine is inadequate

3. The ground caves in

Spoiler alert: the machine got stuck, our plan to deal with the machine is a slow-motion fiasco, and the ground is caving in.

—

Holy Bertha! WSDOT

OK, so, the project gets underway in 2011, scheduled to be done in late 2015.

In July 2013, they bring in Bertha, the largest tunnel-boring machine in the world, built specifically for the project by the Hitachi Zosen Corporation.

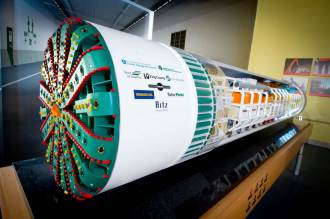

It’s an engineering marvel! There’s a small-scale replica on public view in the historic Pioneer Square neighborhood, the very neighborhood Bertha was to dig beneath.

The massive machine cranks up and jams its enormous snout into the earth, tearing fiercely through rock, soil, and seawater, leaving all the world in awestruck wonder. For a minute, anyway. Then, a thousand feet in — one-tenth of the way through its journey — it grinds to a halt.

No one knows why. For months. It eventually emerges that the machine itself is broken and no one is quite sure how to fix it, or how long it will take. What broke it? Turns out Bertha ran into a large steel pipe that was left there by a WSDOT employee in 2002. Yes, WSDOT killed its own machine. It’s almost poetic. [Correction, 12/16/14: The steel pipe casing was left in the ground not by a WSDOT employee, but by a WSDOT-hired contractor. Also, Seattle Tunnel Partners, which owns Bertha, says the machine broke down due to overheating; neither STP nor anyone is sure exactly why, or whether the pipe casing is to blame.]

Funny story: Bertha has no reverse gear. There’s no way to back it out. The repairs have to be done in situ, which means WSDOT Seattle Tunnel Partners has to dig a 120-foot hole to reach the machine. (It’s pure luck Bertha didn’t get stuck beneath a building, if “luck” is the right word here.)

So that’s what construction crews have been doing for the last few weeks, digging down to Bertha, pumping out salty groundwater as they proceed. It’s going really well!

Here’s the Bertha replica.WSDOT

Ha ha, no, of course it isn’t. Instead, as water is pumped out, the surrounding land has started settling, unevenly, cracking streets and threatening nearby buildings and the viaduct itself.

The viaduct has sunk about an inch in the last few weeks. Is it still safe? WSDOT says so, and I for one can’t think of a single reason to doubt what they say. Ahem.

—

Now, 84 feet down, crews have stopped digging. No one knows exactly how dangerous the settling is or how it will be solved. Meanwhile, they have to keep pumping saltwater out lest the big hole fill up.

Contractors are saying that tunneling will resume next April, pushing completion back into late 2016. But the fact is, that’s more hope and prayer than prediction. The aforementioned Cary Moon, in a new editorial, explains what has to go right for that to happen:

Currently, the rescue operation to remove, repair, and reassemble the TBM [tunnel-boring machine] is under way. This is a high-wire act in itself. If they succeed in digging the remaining 40 feet of the removal pit without causing Pioneer Square buildings to sink, if they can drive the TBM forward into the pit, if they succeed in removing the front end of the machine and lifting it out of the hole, if they can figure out why it failed, if they can install new seals and a new main bearing and add steel to—once again—strengthen the machine, and if they can do it all out there en plein air on the side of the road, then they can reassemble the machine and restart.

After that, another if: if Bertha can make it the rest of the way without stalling again, maybe under a building where there’s no way to reach her.

If all that comes together, the biggest if of all: if, after all the delays and repairs and extra work, the project can still be brought in on budget.

Spoiler alert: You’re more likely to see salmon sprout wings and fly.

—

Like most megaprojects, the tunnel was sold to voters and city leaders through a rose-tinted fantasy that is already in shambles. But no city or state leader seems willing to reverse course.

That is typical. One of the main reasons transportation megaprojects end up being such nightmares is that leaders are terrified of abandoning sunk costs. (Has the term “sunk costs” ever been more apropos?) They will keep throwing public money down holes even as disasters unfold. Anything is better than admitting a catastrophic mistake.

As Holden wrote in a story this July (after Bertha stopped, but before the sinking started), nobody but nobody is taking responsibility for this omni-mess — not City Council, not Murray, not Gregoire, not the contractors, nobody.

Meanwhile, a nasty legal battle with contractors is on the horizon and Seattle taxpayers are already on the hook for several blocks of new water mains around Pioneer Square. It may only be a taste of what’s to come.

People are beginning to speak the unspeakable:

Washington State transportation secretary Lynn Peterson recently acknowledged in a radio interview that there is now a “small possibility” the tunnel will never be finished. Prominent Seattle attorney John Ahlers, who specializes in construction disputes, agrees. “It is entirely likely that, at the end of the day, forces will align and the once touted project to improve Seattle’s waterfront never becomes a reality,” he wrote in a blog post last month.

Whee!

You put your money in it. WSDOT

Mayor Murray has not given up, though. Instead, his message is that the tunnel will go forward but, sorry, Seattle might have to cut back on those other waterfront improvements. This now sets lucky Seattleites up for the worst case scenario: a new tunnel with none of the urban upgrades that were supposed to attend it — a status quo that, many billions of dollars later, is little better for city residents than what preceded it.

But Seattle still has a chance to get out of this. Moon and other activists are now openly calling for the tunnel to be abandoned. There’s still time to let it go and revert to the surface/transit option, which has already been scoped out and would be about a billion dollars cheaper.

Seattle does not need an urban highway, any more than San Francisco, Milwaukee, Portland, Vancouver, Madrid, or Seoul needed theirs. They tore theirs down and the traffic jams did not materialize. Instead their urban cores became more walkable and pleasant, so they attracted more people, more businesses, and more tax revenue. Cities work best when designed for the people who live in them, not the people trying to get through them as quickly as possible.

Still, given the uniform incompetence, willful delusion, and bad faith that have characterized this fustercluck so far, such a positive outcome is unlikely. City leaders seem determined to keep digging.

—–

Next post: Three more reasons Seattle is stuck in a fustercluck