When Dorothy Walker was looking for a place to live in Berkeley, California, it didn’t take her very long to learn that half the city was off-limits to her family. It was 1950, and the rules were clear: “Because my husband was Japanese, we couldn’t live east of Grove Street, because no one not white was allowed to live there.”

Congress outlawed explicitly racist real estate covenants in 1968, and around a decade later, Berkeley changed the name of Grove Street, which divides the wealthier eastern half of the city from the west, to Martin Luther King Jr. Way. But some 70 years after she first went house hunting with her husband, Walker argues that, though the rules that kept the city divided by race and class have evolved, their effects remain.

If you want to know how century-old land-use laws could possibly be relevant today, you can find that lesson in Walker’s story.

Dorothy Alford (later Walker) and Joe Kamiya in 1950 Courtesy of Dorothy Walker

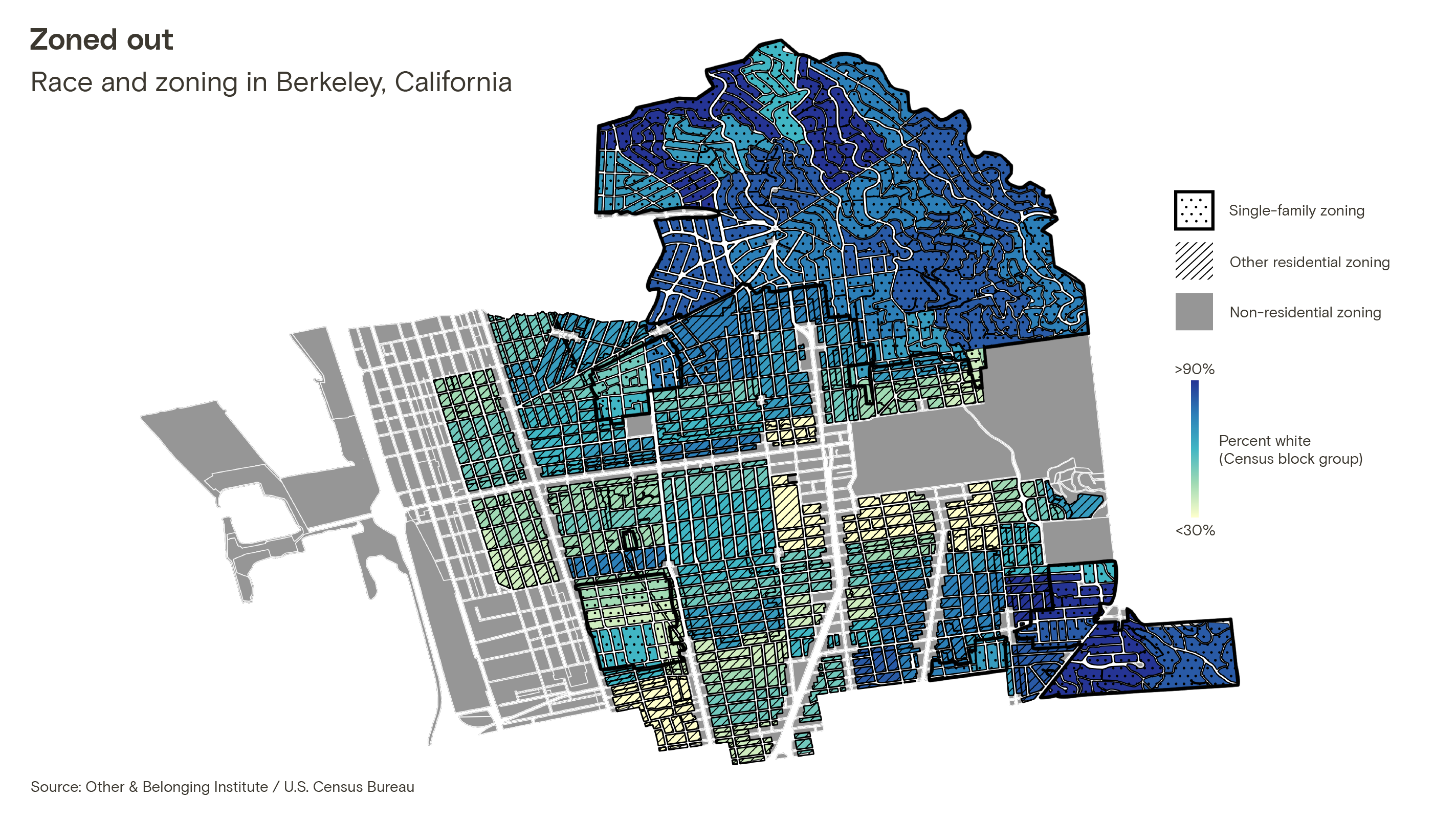

Each time judges or federal lawmakers tried to make racial segregation illegal, starting in 1917, Berkeley and other cities around the country replaced them with ordinances that entrenched segregation by income and wealth instead, reserving certain parts of town for people who could afford their own house and a roomy yard. By requiring only single-family homes set back from their property lines in the white parts of towns, “municipalities basically codified existing patterns of demographics,” said Stephen Menendian, who researches the way policies affect inequality at the University of California, Berkeley.

Walker spent the bulk of her life fighting to open up neighborhoods to more people. Now it’s finally happening: A wave of cities and states are eliminating single-family zoning to allow the development of denser housing stock in previously exclusive areas. Minneapolis legalized triplexes in 2018, and Oregon effectively eliminated single-family zoning the following year. Recently, California and Seattle partially followed Oregon’s lead, allowing people to build small backyard houses without a lengthy review process. In January, Massachusetts told 115 municipalities around Boston to legalize the construction of multi-family buildings, and Sacramento voted to legalize fourplexes. Berkeley’s City Council could join them this week, making Walker’s 50-year dream of a more urban and diverse Berkeley come true.

It’s a long-overdue trend, said Muhammad Alameldin, an economic equity fellow at the Greenlining Institute, an Oakland, California-based nonprofit founded to undo the legacy of race-based housing rules. “The general consensus is that exclusionary zoning raises housing costs, and that disproportionately hurts people of color,” he said. Greenlining and others have prioritized eliminating those practices for decades, Alameldin explained, “but it’s finally getting some momentum because housing costs are starting to hurt the wealthier, whiter residents, as well.”

When Walker and her husband, Joe Kamiya, went looking for a home, there were no scenes or confrontations; landlords simply told them that they’d have to find a place in the western half of the city, as if it were a fact of nature, a result of explicitly race-based neighborhood covenants. It made Walker, who is white, angry. She had already seen how such discrimination could grow into something much worse: Just a few years earlier, the United States had sent some 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent, including Kamiya and his family, to internment camps, and confiscated their homes, businesses, and other property.

In the Jim Crow South, paramilitary groups like the Red Shirts and the Ku Klux Klan enforced the color line. In the north, rules that maintained segregated cities were often unwritten and sometimes enforced by violence. In 1897, white residents of Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood “declared war,” threatening their Black neighbors until they moved out. People were driven from their homes by mobs hurling threats, rocks, and sometimes dynamite. San Francisco was one of the first cities to codify these rules, banning Chinese residents from portions of the city in 1890.

Berkeley’s housing discrimination was more subtle. In 1916, the city passed a zoning plan that permitted only single-family homes in the wealthiest parts of town, which had the effect of banning apartments and other cheaper forms of housing. A prominent realtor, Duncan McDuffie, championed the rules as a means to preserve neighborhood character, and avoid “the evils of uncontrolled development.”

Starting with New York in 1957, states began passing fair housing laws to make this kind of discrimination illegal, but they persisted in California. An assemblyman from Berkeley, William Byron Rumford, pushed through the state’s Fair Housing Act in 1963 only to see Californians vote to overturn the law through a ballot proposition. Finally, in 1968, the Supreme Court struck down the practice and reinstated Rumford’s law.

Around the same time, the country was in upheaval over integrating schools, more than a decade after the Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in 1954. Walker was working as part of a committee to oversee the integration of Berkeley’s schools. The system they devised was one of the most comprehensive in the country. The city bused white students down from the wealthy hills in the east, and up from the working-class flatlands in the west, until every school had a student population with an even spectrum of skin tones. It was the first city with a population of over 100,000 to institute two-way busing voluntarily in 1968. The next year, a little girl from the west side of the city named Kamala Harris would ride the bus east for her first day of kindergarten.

But Walker feels little pride for her contribution to the effort. “It failed almost immediately,” she said.

The schools were mixed, but the students still kept to their neighborhood friends while at lunch and on the playground. Part of the problem was that most of the city’s elementary schools were in the wealthier, eastern part of town. The more affluent parents raised money and volunteered their time to start clubs and enrichment programs for their local schools. “I’m sure the parents didn’t want to exclude anyone, but the buses left right when school was over, and most of the programs were after school, of course,” Walker said. The white kids hung out after school for the chess clubs and sports teams, goofed around, and formed friendships.

According to Walker, by the time the students reached middle school, they’d solidified their peer groups along mostly racial lines. “The Black children were always at a disadvantage because the youngest ones had to be bused,” she said. “What I learned was that the problem wasn’t the schools, it was the surrounding neighborhoods. To really desegregate the schools you need to desegregate the city.”

When the Berkeley City Council asked Walker, who had recently finished her stint on the schools committee, to serve on the planning and zoning commission, she leaped at the opportunity.

The formula seemed clear to her: Diverse neighborhoods need diverse housing options, rooms and apartments that the poor could afford among the big houses of the wealthy. After discussing her idea with a professor and lawyer who urged her on, she proposed eliminating single-family zoning to the rest of the planning commission. She doesn’t remember the year — 1971 or 1972 — but she does remember that her colleagues didn’t exactly embrace her proposal. “I was basically a voice in the wilderness crying out for density,” she said. “It was just so radical. It fell like a stone.”

Instead of loosening restrictions, citizens moved to clamp down. In 1973, Berkeley’s residents put what they called the “Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance” on the ballot to make it harder to demolish old buildings and build new ones. Preservationists who wanted to save historic architecture allied with wealthy hill dwellers who wanted to protect their neighborhoods from change, in tandem with left-wing activists who wanted to stop profit-driven developers. Meanwhile, Black voters were split between those who wanted to open up historically white neighborhoods to integration and supporters of the measure who wanted to hold on to the neighborhoods where many Black families had established a community.

Ben Bartlett, a current member of Berkeley’s City Council who is Black, has suggested that the measure was a means to stop the spread of the growing Black population. Sophie Hahn, another council member, said that many Black residents and their allies saw the ordinance as a way to avoid losing their communities to bulldozers. Over the previous decades, “urban renewal” efforts, most famously led by Robert Moses in New York City, had flattened working-class, Black, and brown neighborhoods to make way for highways and new buildings. In 1955, the city leaders of Roanoke, Virginia, condemned a Black community to make way for a post office and a Ford dealership. In 1962, a Chrystler factory and a new interstate pushed out 4,000 residents from Hamtramck, Michigan, uprooting half the city’s Black residents. Planners also chose Black neighborhoods as the ideal spots for pouring new concrete in Miami, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and across the country. As James Baldwin put it, “Urban renewal means negro removal.”

By 1973, when Berkeley voted on its Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance, the era of urban renewal was over and the pendulum had swung in the opposite direction. It was politically profitable to rail against bulldozers, developers, and new housing. Walker fought “tooth and nail” against the measure, warning it would further entrench the city’s segregated neighborhoods and drive up housing costs. But the ordinance passed by a solid margin.

The decades since have made Walker look like a Cassandra: Berkeley’s land-use restrictions kept developers from building new houses as the state’s population soared, driving up the cost of housing. In the last 70 years, California’s population has nearly quadrupled, while Berkeley’s population count has barely budged: from 114,000 in 1950 to 121,000 more recently. Berkeley’s median home price is now $1.4 million, roughly twice as expensive as the state’s. Meanwhile, the Black population dwindled from 23 percent of the city in 1970 to 8 percent today.

After conducting a granular analysis of the 100-odd municipalities in the San Francisco Bay Area, Stephen Menendian, the UC Berkeley inequality researcher, found that single-family zoning was still functioning “as a mechanism for racial exclusion.” Most of the land in the Bay Area surrounding Berkeley is zoned for single-family homes; just 17 percent is open to other types of housing. The net effect, Menendian said, is to concentrate affluence in some neighborhoods and poverty in others. “As you increase the level of single-family zoning, you have a clear decrease in Latino and African American people in a community,” he said.

Take the Bay Area city of Piedmont. Its population is 70 percent white, its median household income tops $130,000, and it’s entirely zoned for single-family housing. Children there have access to well-supported schools and generate some of the best test scores in California. Just across the border in Oakland, where the white population makes up 28 percent of the city, median household income hovers around $51,000, and 65 percent of the residential land is zoned for single-family housing. Oakland struggles to teach hundreds of homeless students while often overhauling foundering schools. The children lucky enough to grow up in Piedmont also breathe cleaner air and can expect to live 6 to 10 years longer. The zoning keeps most of the money on one side, and most of the problems on the other.

Some version of the same story has played out in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Seattle, St. Louis — where a couple of suburbanites last year brandished guns at Black Lives Matter protesters and warned that President Joe Biden might end single-family zoning — and seemingly everywhere that these zoning rules exist.

Walker takes no joy in her vindication. “We have tried to thwart the law of supply and demand for 50 years, and now we can’t fix it,” she said. “If you wonder why there are 1,200 homeless people living on Berkeley’s streets and why our children can’t afford to live in this town anymore, it’s because of that. We have killed our own future.”

At some point over the past 50 years, people started listening to Walker. Back in 1984, when current California State Senator Nancy Skinner won her first election and took a seat on the Berkeley City Council, she was predisposed to side with conventional wisdom in opposition to market-rate housing. But in 1990, Skinner, a longtime environmentalist, helped start an international association of cities working to fight climate change and, as she worked with these cities, she realized every one of them shared a fundamental problem: Their buildings were spread too far apart, encouraging residents to drive.

“In every one of those cities, except those in very cold climates dependent on coal, transportation was the leading source of greenhouse gas emissions,” Skinner said. “Then I looked at all these studies showing how the automobile dependence was based on land-use decisions and realized we were never going to be able to tackle city emissions unless we tackled land use.”

Skinner soon started turning up at zoning meetings to support new residential construction in Berkeley and found herself working hand-in-hand with Walker. They also teamed up with a young activist named Lori Droste, who would go on to become Berkeley’s vice-mayor. The trio would kick off the process of abolishing single-family zoning. Droste adopted Skinner as a mentor and considers herself one of Walker’s political descendants. “She’s so amazing, and she was so ahead of her time,” Droste said.

In February, Droste wrote an unusually detailed resolution to start the process of opening up the exclusive parts of Berkeley to multi-family homes, then sent it to Walker. As Walker read through the final pages of whereases and therefores, tears formed in her eyes. She is 90 years old. And even though she’d fought for it most of her life, Walker had not expected to live long enough to see Berkeley end single-family zoning.

Plenty of people are still opposed. In a recent council committee meeting, Berkeley residents logged into Zoom to voice their objections. Patrick Sheehan, an architect and former planning commissioner, warned that the proposal might prevent people from fighting efforts to put more homes in their neighborhoods. He claims Droste’s proposal does nothing to create more affordable housing. “It’s a gift to developers by deregulating developments of four units without restriction on the number of bedrooms,” he argued.

Becky O’Malley, the editor of a lefty anti-development newspaper, The Berkeley Daily Planet, fumed over the assertion in Droste’s resolution that the city’s housing restrictions had fueled racial inequality. “I am 81 years old, and I have devoted most of my life to achieve racial equity,” she said. “The idea that a twerp like Lori Droste offends the good Berkeley people of my generation leaves me unable to speak to the substance.”

In the past, the political group O’Malley calls “her age peers” — progressives who cut their teeth protesting against the Vietnam War — won the day with arguments like this. But the political landscape has shifted. Sophie Hahn, the Berkeley council member, has voted in the past to limit development, but now thinks the time is right to allow for more housing. “There’s a big new generation coming up, supplanting the political power of the older generation,” she said.

It makes sense that members of Berkeley’s old guard are getting frustrated with those who suggest that they are reinforcing segregation when they fight to preserve single-family zoning. The people who championed the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance back in 1973 believed zoning rules were a buffer against gentrification and would help Black neighborhoods control their own destiny. “They were good people, with good intentions,” Hahn said.

Perhaps these good-intentioned people couldn’t have anticipated the consequences. Carole Kennerly, who became the first Black woman elected to the Berkeley City Council in 1975, said the ordinance created a tangle of red tape and required homeowners to spend a lot of money preserving architectural details. She was once admiring a beautiful century-old house in a predominantly Black neighborhood when the owner walked up. “She got to describing all the intricacies that she had to go through, and it was off-putting for the family,” Kennerly recalled. “It made it hard for them to keep the house.”

Housing experts agree that loosening zoning won’t bring down Berkeley’s stratospheric housing prices. “There’s no hope; it will never be affordable again,” said Karen Chapple, a city planning professor at UC Berkeley. But making it possible for more people to live in the city, she said, would put less pressure on residents to flee to surrounding cities and tamp down the growth of sprawling exurbs.

There are also environmental benefits that come with greater density, like better bus lines, more walkable neighborhoods, and cleaner air. “People of color suffer disproportionately from emissions and pollution,” said Greenlining’s Alameldin. “Tearing up single-family zoning really does help with that.”

It was about 10:30 in the evening in February, and the Berkeley City Council was prepared to vote on Droste’s resolution. Around 200 residents were logged into the council’s Zoom call, some of them the same who had spoken at the previous meeting. A few described the resolution as an attempt to pick the pockets of the poor for the sake of greedy developers. One speaker after another described supporters of the resolution as either a shill for the real estate industry, racist, or stupid.

For decades, the City Council acceded to arguments like these, squashing efforts to build more housing. On this night, however, a younger voice piped up to support the measure, and another thanked the council. The meeting kept going into the depths of the night. There were so many enthusiastic voices queued up to support the proposal that, as midnight drew near, Mayor Jesse Arreguin asked them to simply say, “I support the resolution” rather than use their allotted minute. When the time came for the roll call at the break of a new day, every single member of the council voted in favor. The political alliances that Walker had spent half a century fighting had been supplanted by a new generation that shared her views.

“For a long time, the Berkeley City Council was dominated by people who were 65 and older,” Councilmember Terry Taplin said. “I’m 32, and I’ve completely given up on the idea that I’ll ever own a home. When we lost our crappy rent-controlled apartment my husband and I had to move into separate places. So those NIMBY arguments about protecting lot size and views aren’t meaningful to me.”

The February vote merely put the City Council on the record as supporting the reforms. To turn Droste’s resolution into reality, and end single-family zoning a century after Berkeley created it, council members must grapple with the details. On Thursday, the council will have a chance to back that resolution with action, as it is scheduled to vote on a proposal that would allow up to four units, then ask the planning and zoning commission to sort out the details. “Who knows how long they are going to be chewing on that,” Droste said. Even if everyone is working in harmony, checking the boxes of California’s environmental quality law generally takes a year and a half.

Walker hopes to live to see her efforts come to fruition. “Think what we could have achieved if we had been providing housing on a regular basis with supply meeting demand,” she said about the decades of time lost defending the zoning practice. “The price of housing would be totally moderate now for everyone.”

The Berkeley she envisioned would be truly urban — many more apartments, fewer front yards, less parking, more buses — and much more diverse, a place where the average elementary school teacher could buy a home.

But that opportunity has passed for good, regardless of whatever the city does with its zoning laws, Walker insisted. The wait has “been too damn long.”