This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

If you have ever been snorkeling in a tropical paradise and seen the psychedelic colors and teeming variety of otherworldly sea critters, you were gazing upon something increasingly rare: a healthy coral reef. That site also does a lot more than dazzle vacationers. Coral reefs occupy just 0.1 percent of the oceans’ bottom but provide habitat to a quarter of the world’s fish species. They also prevent erosion along coastlines and buffer the impact of storms, providing protection, food, and livelihoods for about 500 million people.

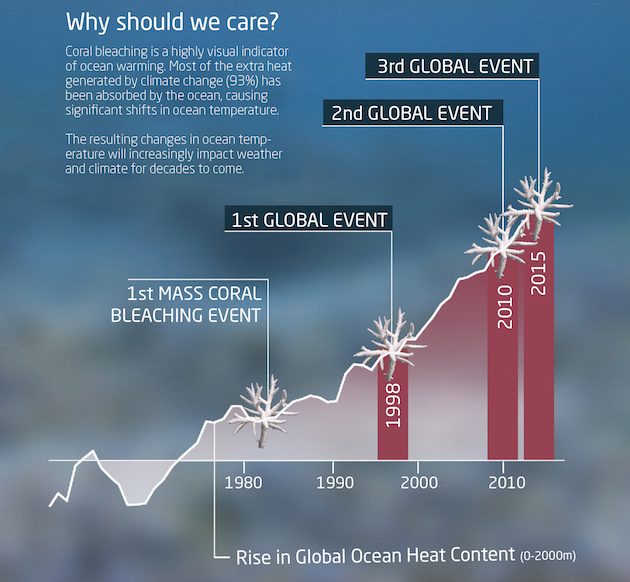

A year ago, I warned that something “really, really terrible” was about to happen to the globe’s corals. Since then, that thing has come to pass. The world over, from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to coastal western Africa, reefs are expelling zooxanthellae, the symbiotic algae that feed them and give them color. That’s because corals can only maintain contact with their algal lifeline under certain water temperatures, and climate change has triggered a decades-long warming of the oceans. Add a particularly powerful El Niño like we’re in now — essentially, cranking up the fire under a simmering pot — and you get what’s known as a “global bleaching event.” We are now experiencing only the third one in recorded history. Here’s a timeline, from the XL Catlin Seaview Survey:

XL Catlan Seaview Survey

There are two particularly disturbing things about this current bleaching event. The first is its duration: It started in 2014 and “could extend well into 2017,” Mark Eakin, who directs Coral Reef Watch for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told me. Already, this is the longest coral bleaching on record — the previous ones lasted less than a year, he says. And he expects that this year, bleaching will expand and “hit more reefs” and be “more extreme” than last year.

The second is how little time has passed since the previous global-scale bleaching, which took place in 2010. Once coral lose their zooxanthellae, they quickly begin to decline in health. But given time, they can recover — and many did between the last two coral bleaching events in 1998 and 2010. But this new one is only four years after the last. The shortened interval between bleachings means less recovery time and more losses, Eakin says.

Warming water isn’t the only way climate change damages corals. About a quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted by burning fossil fuels ends up in the oceans, where it drives down pH levels. As a result, the oceans are currently 30 percent more acidic than they were at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s. Heightened acidity impedes the growth of any species in the oceans that develop hard surfaces — everything from oysters and crabs to, yes, corals. A recent Nature study found that coral reefs grew 7 percent faster under pre-Industrial Revolution pH conditions than they do now. Slower growth makes it harder to recover from recurring insults like bleaching, Eakin says.

Since the 1970s, the Caribbean region has lost 80 percent of its corals and the Great Barrier Reef along the Australian coast has declined by half. Eakin says climate models suggest the Caribbean’s corals face the biggest threat going forward, and they portend a “fairly dire future” for reefs worldwide. If current greenhouse gas emissions hold, he says, by 2050 we could see global bleaching happen every year — in short, a seascape no longer capable of supporting its vital ecosystems, ones that are are richer in biodiversity than rainforests.

The only hope for averting such a fate, he says, is a global greenhouse gas emissions deal that holds global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius. Even then, we’ll also have to address what he calls the “local stressors that act in concert to damage corals,” including overfishing and industrial and agricultural pollution. There’s also a direct effect of all those beach holidays in coral-rich regions. A 2015 study by University of Florida researchers estimated that as much as 14,000 tons of sunscreen lotion enters the ocean in coral reef areas annually. Most of it contains a chemical that makes corals more prone to bleaching at extremely low water concentrations (more here).