Last year, a pair of anthropologists traveled to central Appalachia to talk to locals about the so-called “War on Coal.” They trekked across nine counties in West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, recorded hundreds of conversations, and published the results in a report for the Topos Partnership, a public interest communications firm.

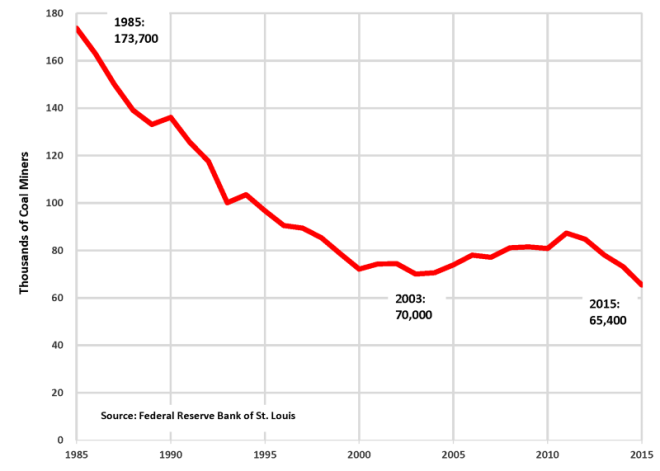

Appalachians told the researchers they want independence, and they believe independence comes from work. Work used to come from coal, but mining jobs are fleeing the region. In the last five years, Kentucky and West Virginia shed 15,000 coal jobs.

“When we have coal, then we have money put into our communities, but when you don’t have coal, your coal miners leave. They go places,” said a woman from Logan County, West Virginia. Coal miners could make upwards of $80,000 a year, and they spent their hard-earned dollars at the grocery down the block and the bar around the corner.

As coal departs, Appalachia is being forced to reinvent itself. Amid reports of economic decline are stories of rebirth, of communities reclaiming their independence.

Computer programming

Kentucky tech startup Bit Source is hiring out-of-work coal miners and teaching them to write code.

“The realization I had was that the coal miner, although we think of him as a person who gets dirty and works with his hands, really coal mines today are very sophisticated, and they use a lot of technology, a lot of robotics,” Rusty Justice, the firm’s cofounder, told NPR. State officials are working to extend high-speed internet access to the Eastern Kentucky to support more ventures like Bit Source that provide well-paid jobs to coal veterans.

Clean energy and energy efficiency

Analysts say the shift to clean power will create more jobs than it eliminates. Enterprising coal workers are trying to bring a few of those jobs to Appalachia.

Retired Kentucky coal miner Carl Shoupe and his colleagues on the Benham Power Board are spearheading a citywide energy efficiency program. Contractors will make homes more power-thrifty — installing insulation, sealing windows, etc. — and homeowners will pay for the upgrades through a charge on their monthly electric bill. The charge will be less than what customers save on energy.

Shoupe believes communities that once ran on coal can add jobs and save money by investing in energy efficiency. According to a report from Synapse, an energy consulting firm, Kentucky could create more than 28,000 jobs by embracing energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Wine growing

In a region wounded by strip mining and mountaintop removal, some families are trying to heal the earth, transforming depleted mining sites into vineyards.

Virginia’s David Lawson built Mountainrose Vineyard on fields that had been strip mined by his grandfathers, according to YES! Magazine. He named wines Jawbone and Pardee after coal seams.

Kentucky’s Jack Looney, the son of a coal worker, built Highland Winery on a strip mine. Looney told the Associated Press that grapes grow well on land cleared by mountaintop removal. His wines pay tribute to the region’s history with names like Blood, Sweat, and Tears and Coal Miner’s Blood.

A culture of pragmatism

Appalachia’s future remains tenuous. Coal is dying. Jobs are vanishing. Skilled workers are fleeing the region. But as the Topos report noted, Appalachians are pragmatic. Said a woman from Pike County, Kentucky, “Try something new — if it doesn’t work, do something else, you know? Just try till you find what works.”

The biggest challenge may be the loss of identity. Difficult, backbreaking, and dangerous though it was, mining gave Appalachians a sense of purpose. It defined a region as gritty and determined. How do you go from wresting energy from the bowels of the earth to writing code or growing wine?

“I wanted to be a coal miner so bad I could taste it … I wanted to have that pride,” said former Virginia coal miner Nick Mullins in an interview. Mullins came to change with his surroundings. When he was 18, a mining company blew the top off the mountain behind the house where he grew up. He never wanted to mine again.

“What is life unless you can live it?” asked Mullins. “What is a community if it’s not there anymore?”

This story was written and produced by Nexus Media.