I was on sabbatical last year when EPA released its draft rule to limit carbon emissions from existing power plants and never really dug into the details. Now I’ve done some digging and I want to do a couple of posts on key aspects of the rule, how it might be strengthened, and how it affects the politics of clean energy.

The rule, known as the Clean Power Plan (CPP), is likely to be the most significant element of Obama’s climate legacy, the policy that fulfills his promises to the international community (China particularly). Climate hawks should have a good grasp on what it does and where’s it’s vulnerable. With their, um, talons. So let’s get into it.

—

The CPP is complicated and involves lots of contentious issues, but one issue in particular looms larger than others. It is what makes the rule so powerful and also what makes it a target for lawsuits.

It is this: The CPP takes a systems-based rather than a source-based approach to emissions. In determining the potential for carbon reductions, it takes into account not just the power plants themselves, but the entire electricity system, all the way down to consumers. It would allow states to reduce emissions through a number of measures that take place outside the power plants, including building out renewable energy and boosting end-use efficiency.

Does EPA have the legal authority to do that? That question is soon to be at the center of a furious legal battle, likely to reach the Supreme Court. To understand the stakes of that battle and the arguments on both sides requires a little background.

—

As I’ve explained before at mind-numbing length, when the Supreme Court cleared the way for EPA to treat CO2 as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act in 2007, and then EPA issued its “endangerment finding” on carbon in 2009, several legal obligations kicked into gear:

- EPA had to regulate mobile sources of CO2, which it did via Obama’s boost in fuel economy standards.

- Then it had to regulate newly built stationary sources of CO2, mostly power plants but also a few big industrial facilities. The agency issued a draft rule in 2012 and then a better draft rule in 2013; it is set to issue a final rule in June.

- Then it had to regulate existing stationary sources, which is what it’s doing with the CPP, also scheduled for final release in June.

EPA is regulating existing power plants through Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act, a little-used provision (five times in the Act’s history) that is being retrofitted to have seismic effects on the power sector.

Under 111(d), EPA is allowed to develop “standards of performance for any existing source” of a regulated pollutant. The performance standard is supposed to reflect “the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction.”

The legal controversy turns on which bit of language you find most significant, “existing source” or “system of emission reduction.”

EPA and enviros argue that the term “system” implies a broad view, taking in not just the technological system of the power plant itself but the electricity system in which the power plant is embedded.

Their opponents argue that the performance standard is meant to apply only to equipment and activities “within the fenceline” of existing power plants; it’s not the power system that has to meet the standard, but each individual regulated source. This is important, because under a systems approach, some individual power plants may emit as much or more than before. (With lots of generation being shifted from coal plants to natural gas plants, many natgas plants will increase their emissions.)

Jeff Holmstead, dirty-energy lobbyist, lawyer, and former head of air quality in George W. Bush’s EPA, says:

EPA’s proposal stretches the term “standard of performance” far beyond the breaking point. Under the Clean Air Act, a “standard of performance” is a requirement (usually an allowable emission rate) that applies to an individual facility and is based on the “best system of emission reduction” that will ensure a “continuous emission reduction” from that type of facility. This is clear from the language of the act and almost 40 years of regulatory history. Even now, EPA agrees with this reading of the statute when it comes to new power plants. But when it comes to existing power plants, this term is somehow transformed into a requirement that applies to the state as a whole — a statewide allowable emission rate that varies dramatically from state to state based on EPA’s view of how the entire “electricity system” in each state, including both supply and demand, should be changed over the next 15 years. It is highly unlikely that EPA’s rather breathtaking new interpretation of a 40-year-old statutory provision will stand up in court.

(For another argument that EPA’s interpretation is likely to be struck down in court, see this paper from lawyers Brian Potts and David Zoppo.)

If Holmstead et al. get their way, the effect of the rule will be limited to technology upgrades on the power plants themselves. EPA would like to make a far deeper toolbox available to states to reduce emissions.

In the case of power plants, this is an enormous, crucial difference. Most of the biggest carbon polluters are coal power plants. When it comes to reducing carbon dioxide emissions from coal plants via technology upgrades, there are very few options. It’s either efficiency upgrades in heat conversion, a marginal, single-digit change, or carbon capture and sequestration, which can reduce coal plant emissions by over half but is extremely expensive and not very well demonstrated. (RIP, Futuregen.) It’s a pea-shooter or a bazooka.

The only way past this dilemma — a weak rule (which is what Holmstead wants) or a too-strong rule (and subsequent political backlash) — is to allow states to comply with the rule via emission reductions that take place “beyond the fenceline” of the individual power plants.

EPA and enviros argue that the law authorizes a systems approach. In this short Q&A, the Natural Resources Defense Council makes the case:

Some argue that the “best system of emission reduction” is limited to measures implemented by each source itself (i.e., measures that are “within-the-fenceline,” or “source-based”). … The term “best system of emission reduction” points toward a broader perspective.

To be sure, the EPA’s initial Section 111(d) standards, set during the 1970s, followed the source-based approach. Those standards typically covered a small number of isolated sources emitting pollutants of primarily local concern. An example is the standard for fluoride emissions from existing primary aluminum smelters.

In contrast, the EPA included system-based measures in its 1995 standard for existing municipal waste combustors (MWCs). That standard allows nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions credit trading between individual combustors.

When it came to MWCs, EPA established a systems-based approach (an emission credit trading system) rather than source-based approach. So moving beyond the fenceline is not entirely unprecedented.

But let’s be real, even credit trading between MWCs only involves MWCs. What EPA is proposing with the CPP is to involve not only coal power plants, but the system of coal power plants, natural gas power plants, renewable energy generators, and power consumers. It seems fair to me to say that it’s, if not entirely unprecedented, at least bold.

—

Side note: The systems approach was recommended by NRDC in its influential policy brief of 2012. EPA rightly bristles at the goofy GOP accusation that it simply lifted its plan from the brief — there are numerous, substantial differences — but at its core, the CPP carries NRDC’s imprint.

Which, good for EPA and good for NRDC! That’s what public agencies are supposed to do: Adopt the best, most cost-effective ideas available.

—

The right’s position is unstable in one important way. Conservatives argue that power producers should have a wide array of compliance options, so that there’s flexibility and lower costs, but that the full array of compliance options shouldn’t be taken into account when setting the performance standard, only within-the-fenceline stuff.

That position runs afoul of the “symmetry principle”: “Any adequately demonstrated system of emission reduction eligible for compliance with a performance standard must also drive the standard’s stringency.” (That’s from a Harvard paper that finds the principle “in the language of Section 111 and in the case law.”) If it is possible for a power producer to make use of, say, end-use energy efficiency to reduce emissions, then EPA must take that into account when setting the performance standard.

In fact, if EPA issues a performance standard that doesn’t take into account an adequately demonstrated, cost-effective compliance measure, it is legally vulnerable from that side. After all, a system of emission reductions that eschews practical compliance options is not the “best” system.

So it is either:

- illegal for EPA to take beyond-the-fenceline compliance measures into account when setting carbon performance standards, or

- illegal for it not to.

One way or the other, the courts will have to settle the question.

—

Which side has the better case? I think it’s EPA, not because beyond-the-fenceline is the right answer so as much as the practical structure of these regulations renders the fenceline controversy kind of moot.

To understand why, let’s recall the difference between two phases of the process, standard setting and compliance.

First, EPA sets a performance standard for each state. To do that, it has to determine what power-plant emission reductions are reasonable and cost-effective given the “best system of emission reduction” (BSER) for that state. This is where the systems approach comes in.

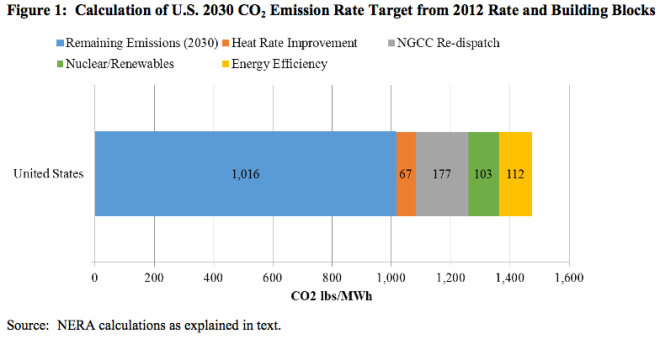

EPA has determined that the BSER will include four basic building blocks:

- Make existing power plants more efficient. (Assumes an average 6 percent improvement in heat-rate conversion.)

- “Load shift” more generation from coal plants to natural gas power plants, which have roughly half the CO2 emissions. (Assumes natgas plants run at average 70 percent capacity.)

- Use more renewable and nuclear energy.

- Increase end-use energy efficiency.

The relative contribution of the building blocks is shown in this graph from consulting firm NERA:

(The NERA report, commissioned by groups like the National Mining Association, is absurdly negative about the costs of EPA’s rule.)

EPA has set bespoke targets for each state and put about five kajillion pages of supporting material online if you want to get into the details. Though it’s been widely misreported otherwise, the CPP has no binding national target. The target of a 30 percent emissions cut by 2030 (from 2005 levels) that’s bandied about is simply the sum of the state targets.

What’s significant is that the systems approach comes into play only in the standard-setting phase, the determination of state-by-state performance standards. Everything from that point forward is about compliance.

EPA does not take a systems approach to compliance. It doesn’t take much of any approach. It leaves the question of how to comply with the performance standard almost entirely up to the states. (This is the flexibility states said they wanted; read more about it in this post from NextGen’s David Weiskopf.) It cannot mandate that states build more renewable energy or implement energy-efficiency programs — as opponents rightly say, that is outside its jurisdiction — and it does not attempt to. It only mandates that power plants meet the performance standard; it only measures CO2 emissions from power plants.

States are supposed to develop their own implementation plans, and EPA has signaled that it will allow just about any compliance regime. If states want to meet the standard entirely through technological upgrades to coal plants, they can. (It would be expensive as hell, but they can.) They can translate the standard into a “mass-based” standard, which tells utilities how many tons of emissions they are allowed. They can translate it into a “rate-based” standard, which establishes a permissible level of emissions-per-megawatt-hour. They can establish cap-and-trade systems, within states or among multiple states. States will no doubt propose other compliance mechanisms.

The point is, EPA is not imposing compliance measures “beyond the fenceline.” It’s not imposing any particular compliance measures. All it’s doing is establishing a performance standard; all it is measuring, or regulating, is CO2 from power plants.

Regardless, all these compliance measures are, in the end, things power generators do. They get more efficient, or they ramp down their output because other power plants are ramping up theirs, or they buy credits for renewables or efficiency. They can do all of that from inside the fenceline. Though some of these measures have effects beyond the fenceline, it is only the power plants themselves, the regulated entities, whose compliance is being measured and assessed. So the whole fenceline discussion is a bit of a red herring.

—

That doesn’t necessarily mean the judges will see it that way. When a case is inevitably filed against the CPP, the case will go before the D.C. Circuit Court at some point, probably a three-judge panel, and much depends on which three judges are chosen. As I wrote in this post, there are some antediluvian fruitcakes on the D.C. Circuit, including Janice Rogers Brown, who thinks most 20th century U.S. legislation (to say nothing of the 21st century) is unconstitutional. This matters, because even if the case goes to the Supreme Court, lots of smaller questions are likely to be decided in the lower court.

What about SCOTUS?

Everything turns on how to interpret the language of 111(d). There are two key issues before the court.

First, there is contradictory language in 111(d), from way back in 1990, when the Senate adopted one amendment (which would authorize what EPA is doing today) and the House adopted another (which wouldn’t). The two contradict one another. You can find the details in this post by Kate Konschnik, director of Harvard Law School’s Environmental Policy Initiative.

Typically, when statutory language is ambiguous, the court has given executive agencies wide latitude to interpret it, as long as the interpretation is “reasonable.” This is known as the Chevron doctrine, after the 1984 case Chevron vs. NRDC.

But is 111(d) language ambiguous or flatly contradictory? As Jack Lienke noted in a Grist post last year, the Supreme Court faced a similar dilemma in a case last session called Scialabba v. Cuellar de Osorio, which dealt with contradictory statutory language. Kagan, Ginsburg, and Kennedy invoked Chevron and deferred to the Board of Immigration Appeals, the executive agency charged with implementing the statute. But, writes Lienke:

Chief Justice Roberts, writing for himself and Justice Scalia, disagreed that the two clauses were truly in conflict but, even more importantly, rejected the idea that Chevron was “a license for an agency to repair a statute that does not make sense.” In Roberts’ view, “Direct conflict is not ambiguity, and the resolution of such a conflict is not statutory construction but legislative choice.”

Could Roberts take the same line on 111(d)? And could he bring a majority along with him? We’ll see. (As Lienke notes, if Roberts throws out both amendments, 111(d) will revert to its pre-1990 form, which would still authorize EPA’s rule.)

Second, there’s the beyond-the-fenceline issue, dealing with how “best system of emission reductions” should be interpreted. Again, the conventional thing would be to invoke Chevron and defer to EPA. Given that a great deal rests on this interpretation, however, the court’s conservatives are likely to be suspicious.

Nathan Richardson of Resources for the Future draws attention to a telling passage in Justice Antonin Scalia’s June ruling in the UARG v. EPA case, which also addressed EPA’s authority to regulate carbon:

When an agency claims to discover in a long-extant statute an unheralded power to regulate “a significant portion of the American economy” … we typically greet its announcement with a measure of skepticism. We expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign an agency decisions of vast “economic and political significance.”

In that opinion, Scalia not only weighed in on a statutory ambiguity, but his “plain meaning” interpretation was directly at odds with EPA’s, which risks “undermining Chevron,” says Richardson.

It may be that an ambitious and increasingly political conservative bloc on the Court will simply interpret 111(d) narrowly, as source-based rather than system-based, Chevron and other precedent be damned. Again, the question is whether they can eke out a 5 to 4 majority for it. For the record, I don’t think so, but no one knows for sure. When the case approaches, we’ll follow along as more knowledgeable SCOTUS observers weigh in.

(Also, check out our own Ben Adler’s great post on CPP’s legal vulnerabilities from last year.)

—

One twist: EPA rather cleverly constructed the CPP so that the building blocks are, in the jargon, “severable.” As lawyer Brian Potts writes:

The agency structured the rule so that if a court finds any of these four building blocks unlawful, the remaining blocks can remain.

So, for example, if a court found that EPA’s renewable or energy efficiency assumptions were unlawful, the rule would just unravel a bit; it wouldn’t come completely undone.

Severability means that an ambitious systems approach was not an all-or-nothing gamble.

—

The CPP will have significant and unanticipated effects not only on the electricity system but on the politics of clean energy. In some quarters it could serve as evidence that no further clean-energy policy is needed (after all, EPA has taken care of it); in others, it could revive the push for ambitious state renewable and efficiency standards (which could go beyond EPA standards). At the international level, it could serve as a clear signal that the U.S. is living up to its commitments.

But all its impact, all its power and ambition, depends on taking a system-level approach. Without that, it will be substantially hobbled. So when the Supreme Court takes up that question, it will represent the most important case for U.S. climate policy since Mass v. EPA.