This story was originally published by Huffington Post and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

It should come as no surprise that human activity is causing the world’s oceans to warm, rise, and acidify.

But an equally troubling impact of climate change is that it is beginning to rob the oceans of oxygen.

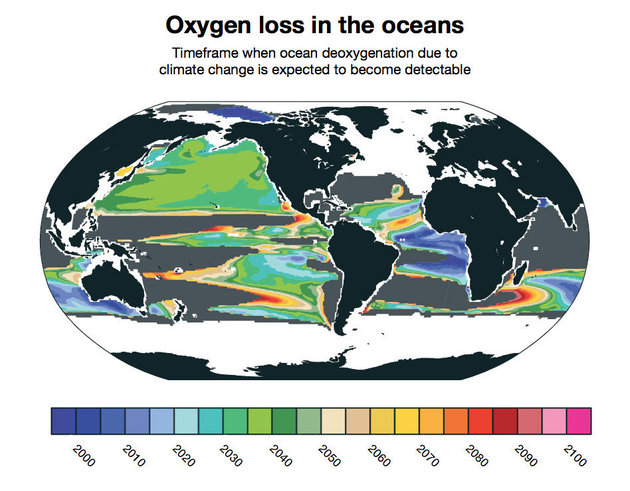

While ocean deoxygenation is well established, a new study led by Matthew Long, an oceanographer at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, finds that climate change-driven oxygen loss is already detectable in certain swaths of ocean and will likely be “widespread” by 2030 or 2040.

Ultimately, Long told The Huffington Post, oxygen-deprived oceans may have “significant impacts on marine ecosystems” and leave some areas of ocean all but uninhabitable for certain species.

While some ocean critters, like dolphins and whales, get their oxygen by surfacing, many, including fish and crabs, rely on oxygen that either enters the water from the atmosphere or is released by phytoplankton via photosynthesis.

But as the ocean surface warms, it absorbs less oxygen. And to make matters worse, oxygen in warmer water, which is less dense, has a tough time circulating to deeper waters.

For their study, published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, Long and his team used simulations to predict ocean deoxygenation through 2100.

“Since oxygen concentrations in the ocean naturally vary depending on variations in winds and temperature at the surface, it’s been challenging to attribute any deoxygenation to climate change,” Long said in a statement. “This new study tells us when we can expect the impact from climate change to overwhelm the natural variability.”

And we don’t have long.

Matthew Long/NCAR

By 2030 or 2040, according to the study, deoxygenation due to climate change will be detectable in large swaths of the Pacific Ocean, including the areas surrounding Hawaii and off the West Coast of the U.S. mainland. Other areas have more time. In the seas near the east coasts of Africa, Australia, and Southeast Asia, for example, deoxygenation caused by climate change still won’t be evident by 2100.

Long said the eventual suffocation may affect the ability of ocean ecosystems to sustain healthy fisheries. The concern among the scientific community, he said, is that “we’re conceivably pushing past tipping points” in being able to prevent the damage.

Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State University, shared these concerns, telling The Washington Post that the new study adds to the “list of insults we are inflicting on the ocean through our continued burning of fossil fuels.”

“Just a week after learning that 93 [percent] of the Great Barrier Reef has experienced bleaching in response to the unprecedented current warmth of the oceans, we have yet another reason to be gravely concerned about the health of our oceans, and yet another reason to prioritize the rapid decarbonization of our economy,” Mann said.

Unfortunately, this reason is unlikely to be the last.