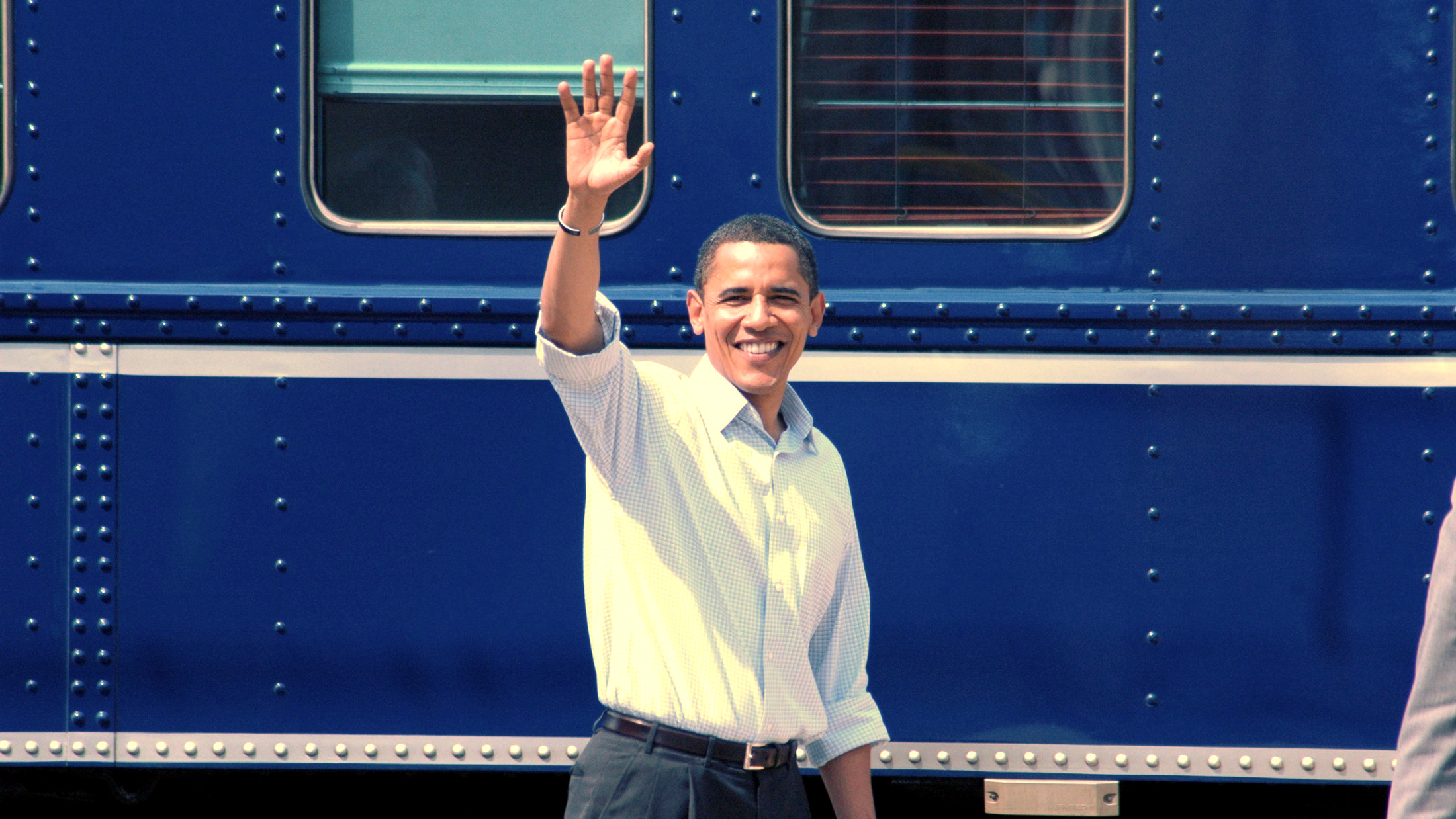

At times, I become really, really curious about the Barack Obama we’re going to see once he’s done being president. He has a gift for talking about complex and unpleasant issues — one that has, for the most part, been submerged by political expediency, but that still pokes through occasionally. This interview with The Economist, conducted on Air Force One by John Micklethwait and Edward Carr, is one such occasion — and offers some encouraging signals about his administration’s approach to climate change.

For instance, during a discussion about the relationship between the White House and the business community, Obama, unprompted, segues into a discussion of denialism and carbon pricing.

Mr Obama: Well, I think—here’s what’s interesting. There’s a huge gap between the professed values and visions of corporate CEOs and how their lobbyists operate in Washington. And I’ve said this to various CEOs. When they come and they have lunch with me—which they do more often than they probably care to admit (laughter)—and they’ll say, you know what, we really care about the environment, and we really care about education, and we really care about getting immigration reform done—then my challenge to them consistently is, is your lobbyist working as hard on those issues as he or she is on preserving that tax break that you’ve got? And if the answer is no, then you don’t care about it as much as you say.

Now, to their credit, I think on an issue like immigration reform, for example, companies did step up. And what they’re discovering is the problem is not the regulatory zealotry of the Obama administration; what they’re discovering is the dysfunction of a Republican Party that knows we need immigration reform, knows that it would actually be good for its long-term prospects, but is captive to the nativist elements in its party.

And the same I think goes for a whole range of other issues like climate change, for example. There aren’t any corporate CEOs that you talk to at least outside of maybe—no, I will include CEOs of the fossil-fuel industries—who are still denying that climate change is a factor. What they want is some certainty around the regulations so that they can start planning. Given the capital investments that they have to make, they’re looking at 20-, 30-year investments. They’ve got to know now are we pricing carbon? Are we serious about this? But none of them are engaging in some of the nonsense that you’re hearing out of the climate-change denialists. Denialists?

Eric Schultz (deputy press secretary): Deniers.

The Economist: Deniers.

Mr Obama: Deniers—thank you.

The Economist: Denialists sounds better. (laughter.)

Mr Obama: It does have more of a ring to it.

So the point, though, is that I would take the complaints of the corporate community with a grain of salt. If you look at what our policies have been, they have generally been friendly towards business, while at the same time recognising there are certain core interests—fiscal interests, environmental interests, interests in maintaining stability of the financial system—where, yes, we’re placing constraints on them. It probably cuts into certain profit centres in their businesses. I understand why they would be frustrated by it, but the flip side of it is that they’d be even more unhappy if the global financial system unravels. Nobody has more of a stake in it than them.

Yup. The president is saying it — but it reads like something straight out of the Unburnable Carbon report, or this summer’s Risky Business project. Coming from a president whose approach to tackling climate change has been slower and more behind-the-scenes than activists would like, this is interesting, and might even bode well for the UN Climate Summit this September.

Not all of the Economist interview is this encouraging. For example, Obama says, as he’s said before, that he thinks the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership (TPP) will be a great idea.

This is not a view widely held by people who are concerned about the way that trade agreements like the TPP can be used to override local environmental laws. Specifically, alarms have been raised over the way that the agreement would allow any foreign-based company with investments here to sue America for damages via secret tribunal if they think our environmental or labor laws are affecting their ability to make money.

The agreement has also been criticized for failing to do anything to discourage trade partners from buying illegally logged or mined or fished or captured goods from one another — at a point in history where pretty much everyone is on the same page about there not being enough fish or trees to go around.

So the president isn’t going to please every green voter. But he’s definitely causing ears to perk up.