One of climate change’s most important biographers — a 2,700-pound satellite orbiting 450 miles above the surface of the Earth — just recorded its last data point.

Earlier this month, the National Snow and Ice Data Center announced that, after nine years and five months in orbit, the satellite known as F17 had stopped transmitting sea ice measurements. That’s not unusual — satellites in F17’s series, all named sequentially, are normally expected to last about five years, though some make it much longer. But F17’s failure could preempt the end of the series entirely. Walter Meier, a sea ice researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, called the satellite program “one of the longest, most iconic datasets” illustrating climate change, particularly in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Since 1978, the satellites, each equipped with a set of passive microwave sensors, have been recording conditions on Earth, day in and day out. By measuring the amount of radiation given off by the atomic composition and structure of different substances, like ice or seawater, microwave sensing is a useful tool for pilots and military officers tracking weather conditions. Over time, these measurements can also track cumulative changes in sea ice. As early as 1999, scientists saw that sea ice cover was decreasing more quickly than it had in previous decades — and they’ve been observing similar trends ever since.

Until now, there have always been three or four satellites in the series orbiting at a time, as part of one of the country’s oldest satellite programs, the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP). Over time, as new satellites were launched and older models went dark, overlapping data have kept the 40-year sea-ice dataset consistent.

With F17 floating in unresponsive silence, the bulk of the responsibility has been placed on F18, launched in 2009, as the newest of the series still in working condition (a newer satellite, F19, was launched in 2014 but failed last February). It’s not ideal to rely on a 7-year-old satellite, says Meier, but at least it is possible to keep the dataset continuous — for now. If this one were to conk out, too (knock on wood), there are some other options, including a Japanese research satellite launched in 2011. But, Meier says, the sensors vary slightly, and the data simply won’t be as consistent.

“The real problem is that there’s nothing on the horizon,” said Meier. “There’s nothing funded, or planned right now.”

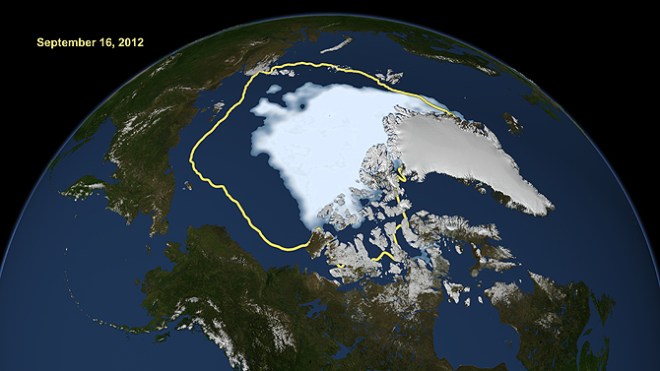

Arctic sea ice extent hit a new low in 2012, compared to the average minimum extent over the previous 30 years.

There is one other option — but it’s sitting in a storage room somewhere on Earth. This satellite, F20, was the last of its series to be built, and was tentatively planned to launch in 2018. That plan fell through last June, when the Senate Appropriations Committee revoked funding for the DMSP, even rescinding $50 million that had been specifically designated for launching F20. Without Congressional approval, F20 is grounded.

“It’s sitting there, ready to be launched,” said Meier. He pointed out that the data from the satellite series is also used to study snow cover on land, ocean currents, temperature change, drought detection, and many other natural cycles. “The benefit is beyond my own work on sea ice.”

That research, he said, has led to critical discoveries. One of the most important was the observation of record-low sea-ice cover in 2007 and in 2012, findings that Meier says went even further than those reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“All of sudden, it was like, ‘Whoa! The ice cover is not as resilient as we thought, and things are moving a lot faster than we expected,’” he said, worrying that if another satellite were to fail, these kinds of observations would be jeopardized. “It would be a real shame if this data gets interrupted.”