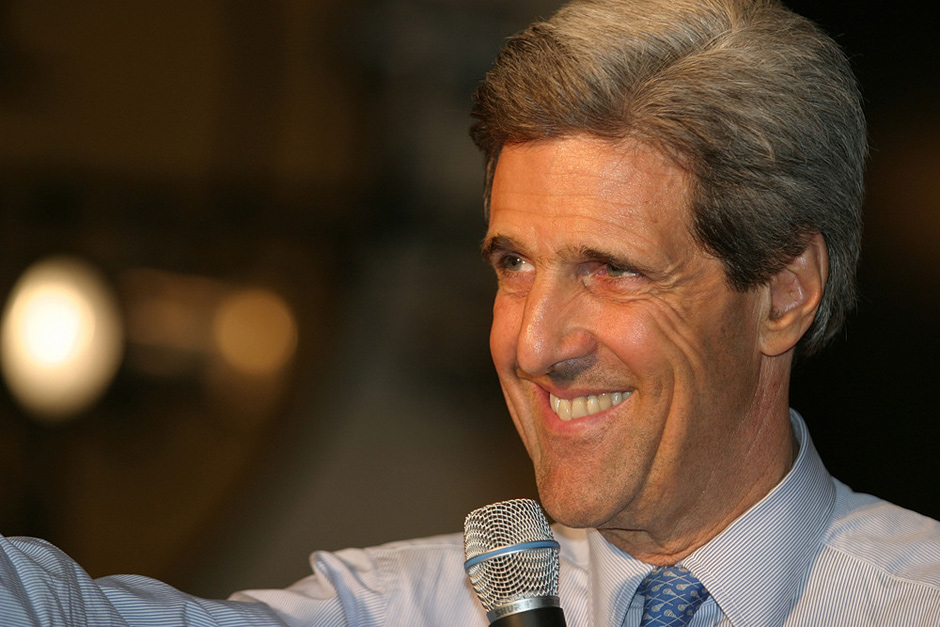

John Kerry, likely future secretary of state.

If Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) becomes secretary of state, as is expected, he’ll be the most ardent climate hawk ever to hold the office. But how much will that matter?

Kerry has been pushing for national and international solutions to climate change for two decades, and he understands that it’s a geopolitical problem, not just an environmental one. “Global climate change is a security issue on a planetary scale,” Kerry told Grist in 2007. In a speech on the Senate floor this past June, he said, “Climate change is one of two or three of the most serious threats our country now faces, if not the most serious, and the silence that has enveloped a once robust debate is staggering for its irresponsibility.” Just this week, Kerry introduced a bill that would help communities become more resilient so they can better withstand the weather disasters brought about by climate change.

“For climate hawks, having Kerry at the helm at State would be very good news,” writes Kate Sheppard at Mother Jones. Climate Progress blogger Joe Romm argues that Kerry’s nomination would be “the first serious indication Obama will focus on climate change in his second term.” And Coral Davenport at National Journal writes that Kerry would “likely raise climate change to a top-tier priority”:

“No senator since Al Gore knows as much about the science and diplomacy of climate change as Kerry,” said David Goldwyn, an international energy consultant who served as Clinton’s special envoy and coordinator for international energy affairs. “He would not only put climate change in the top five issues he raises with every country, but he would probably rethink our entire diplomatic approach to the issue.”

Kerry has been engaged with climate policy since he attended the first major U.N. climate summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. He was coauthor, along with Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Joe Lieberman, ID-Conn., of sweeping legislation that would have capped U.S. emissions of greenhouse gases, although the bill fell apart before making it to the Senate floor. In 2007 he and his wife, Teresa Heinz Kerry, coauthored a book, This Moment on Earth: Today’s New Environmentalists and Their Vision for the Future. …

While many lawmakers speak passionately about climate change, Kerry has also logged years doing the thankless behind-the-scenes work of climate diplomacy and in the process has earned the respect of the rest of the world on the issue.

He was the only U.S. senator to attend key U.N. climate-change negotiations in Bali, Indonesia, in 2007, and Poznan, Poland, in 2008. At a major climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 2009, Kerry arrived before President Obama and Secretary Clinton and spent time in back-room meetings with ministers from China, India, and several European countries to help pave the way for final negotiations.

Still, Kerry takes a realpolitik approach to fossil fuels. Here’s what he told Grist in September when asked about the “all-of-the-above” energy strategy being promoted by Obama and the Democratic establishment:

Look, I’m the most ardent advocate up here for doing something about climate change, but you’re nevertheless gonna have to use fossil fuels. The question is, can you use them in clean and manageable ways? The answer is, Yes, you can, if you make the right sort of requirements. …

If you’re going to use X amount of fuel and you’re using it in a clean way, it’s better to have it produced from the United States than to be dependent on other countries. So, do you want to expand it overall? No. Overall you want to find alternatives in renewables and other things. But you have to do what you have to do to meet our energy demand. You have to have scrubbers, you have to have standards, you have to take old power plants out of service and put in new power plants with higher standards. There are ways to do fossil fuels responsibly. And if we don’t do that, it’s gonna be catastrophic.

What would that sort of thinking mean when it comes to the proposed Keystone XL pipeline? Climate activists are anxious to find out. The State Department will decide in 2013 whether to approve the northern half of the pipeline, which would carry tar-sands crude from Alberta across the U.S-Canada border and down toward the Gulf Coast. Enviros were pleased that U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice took her name out of the running for secretary of state; she has investments in pipeline builder TransCanada and other companies with a stake in Keystone.

Kerry has said very little on Keystone, and has been cautious in what he has said, perhaps not wanting to ruffle feathers while seeking the top job at State.

In 2011, in his role as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kerry promised a careful review of the pipeline proposal but didn’t say he was opposed: “There’s a lot at stake here and I’ll do my best to leave no question unanswered including every possible economic and environmental consideration before a final decision is made.” That statement came after Friends of the Earth accused him of failing to “lead in investigating the oily influence scandal surrounding the Keystone XL pipeline.”

Romm gives Kerry the benefit of the doubt on the Keystone question:

I’m not sure Kerry could become Secretary of State fast enough to influence the Keystone XL pipeline decision, but it is hard to believe he would not have raised this issue with the President, since a go-ahead decision would immediately undercut the Administration’s credibility on the climate issue both at home and abroad.

Still, whether the issue at hand is Keystone or international climate negotiations, how much power does a secretary of state in the Obama administration really have?

Hillary Clinton, though she disappointed greens with her inclination to approve Keystone, certainly understands the threat of climate change and the promise of clean energy — and that hasn’t made a whole lot of difference. She’s launched notable initiatives to fight climate pollutants other than CO2 and spread clean cookstoves to developing countries, but on the bigger issues, progress has been halting at best. The U.S. still gummed up the works at the recent U.N. climate conference in Qatar.

Ultimately, foreign policy is decided in the West Wing. “This is an administration where most of the policy-setting in international relations is done inside the White House,” as Karen Tumulty of The Washington Post recently put it.

Kerry could be a critical advocate for climate action within Obama’s Cabinet, but ultimately it’s the president who will make the big calls on climate deals, Keystone, and so much else.