Is fracking for natural gas good for the planet?

To understand the pitched fight over this question, you first need to realize that for many years, we’ve been burning huge volumes of coal to get electricity — and coal produces a ton of carbon dioxide, the chief gas behind global warming. Natural gas, by contrast, produces half as much carbon dioxide when it burns, and thus, the fracking boom has been credited with a decline in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. So far so good, right?

Umm, maybe. Recently on our Inquiring Minds podcast, we heard from Anthony Ingraffea, a professor of engineering at Cornell University, who contends that it just isn’t that simple. Methane (the main component of natural gas) is also a hard-hitting greenhouse gas, if it somehow finds its way into the atmosphere. And Ingraffea argued that because of high leakage rates of methane from shale gas development, that’s exactly what’s happening. The trouble is that methane has a much greater “global warming potential” than carbon dioxide, meaning that it has a greater “radiative forcing” effect on the climate over a given time period (and especially over shorter time periods). In other words, according to Ingraffea, the CO2 savings from burning natural gas instead of coal is being canceled out by all the methane that leaks into the atmosphere when we’re extracting and transporting that gas. (Escaped methane from natural gas drilling complements other preexisting sources, such as the belching of cows.)

But not every scientist agrees with Ingraffea’s methane-centered argument. In particular, Raymond Pierrehumbert, a geoscientist at the University of Chicago, has prominently argued that carbon dioxide “is in a class by itself” among greenhouse warming pollutants, because unlike methane, its impacts occur over such a dramatic timescale that they are “essentially irreversible.” That’s because of carbon dioxide’s incredibly long-term effect on the climate: Given a large pulse of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, much of it will still be there 10,000 years later. By contrast, even though methane is much more potent than carbon dioxide over a short timeframe, its atmospheric lifetime is only about 12 years.

Applied to the debate over natural gas, that could mean that seeing gas displace coal is a good thing in spite of any concerns about methane leaks.

To hear this counterpoint, we invited Pierrehumbert on Inquiring Minds as well. “You can afford to actually have a little bit of extra warming due to methane if you’re using its a bridge fuel, because the benefit you get from reducing the carbon dioxide emissions stays with you forever, whereas the harm done by methane goes away more or less as soon as you stop using it,” he explained on the show. You can listen to the interview — which is part of a larger show — below, beginning at about 4:40 (or you can leap to it by clicking here):

Pierrehumbert’s arguments are based on a recent paper that he published in the Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Sciences, extensively comparing carbon dioxide with more short-lived climate pollutants, like methane, black carbon, and ozone. The paper basically states that the metric everybody has been using to compare carbon dioxide with methane, the “global warming potential” described by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, is deeply misleading.

The IPCC, in its 2013 report, calls global warming potential the “default metric” for comparing the consequences, over a fixed period of time, of emitting the same volume of two different greenhouse gases. And according to the IPCC, using this approach, methane has 84 times the atmospheric effect that an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide does over a period of 20 years. But, it’s crucial to remember that that’s over 20 years; at the end of the period, the carbon dioxide will still be around and the methane won’t. The metric, writes Humbert, is “completely insensitive” to any damages due to global warming that occur beyond a particular time window, “no matter how catastrophic they may be.” Elsewhere, he calls the approach “crude.”

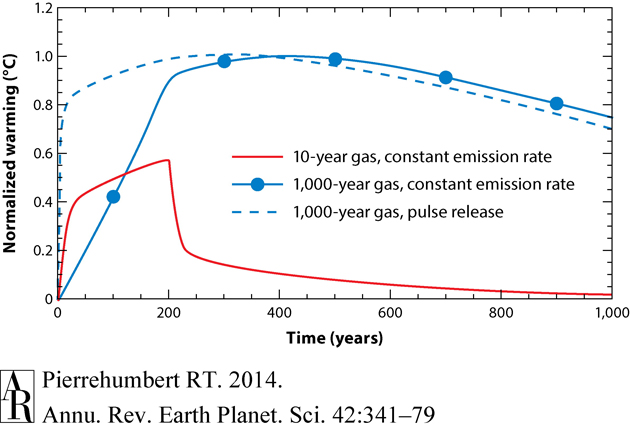

To see why, consider this figure from Pierrehumbert’s paper, comparing the steady emission, over 200 years, of two hypothetical greenhouse gases (the solid blue and red lines). One gas lasts in the atmosphere for 1,000 years, and one that lasts only 10 years. Each has the same “global warming potential” at 100 years, but notice how the short-lived gas’ warming effect vanishes almost as soon as the emissions of it end:

Comparison of two greenhouse gases that have the same “global warming potential” over 100 years but very different lifetimes.

The gases in the figure aren’t carbon dioxide and methane, but you get the point. The upshot, Pierrehumbert argues, is that it is almost always a good idea to cut CO2 emissions — even if doing so results in a temporary increase of methane emissions from leaky fracked wells. As he writes:

… there is little to be gained from early mitigation of the short-lived gas [methane]. In contrast, any delay in mitigation of the long-lived gas ratchets up the warming irreversibly … the situation is rather like saving money for one’s retirement — the earlier one begins saving, the more one’s savings grow by the time of retirement, so the earlier one starts, the easier it is to achieve the goal of a prosperous retirement. Methane mitigation is like trying to stockpile bananas to eat during retirement. Given the short lifetime of bananas, it makes little sense to begin saving them until your retirement date is quite near.

And that, in turn, implies that any displacing of coal with natural gas is a good thing for the climate. It’s just less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, plain and simple.

Ingraffea disagrees. By email, he commented that Pierrehumbert “is correct that the long-term risk to climate is from CO2, but he is willing to accept the almost certain short-term consequences which can only be ameliorated by reductions in methane and black carbon.”

But interestingly, there is one major commonality between Ingraffea’s point of view and that of Pierrehumbert. Namely, both emphasize the importance of getting beyond natural gas, and transitioning to 100 percent clean energy.

Here’s the logic: Because carbon dioxide is so bad for the climate, the fact that natural gas burning does produce some of it (even if not as much as coal) means that if cheap natural gas discourages the use of carbon-free sources like nuclear, solar, or wind energy, then that’s also a huge climate negative. So just as natural gas is not nearly as bad as coal from a carbon perspective, it is also not nearly as good as renewable energy. And that, in turn, means that while natural gas can play a transitional role toward a clean energy future, that role has to be relatively brief.

“It’s useful as a bridge fuel,” says Pierrehumbert, “but if using it as a bridge fuel just drives out renewables and other carbon-free sources of energy, it’s really a bridge to nowhere.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.