As Chilean President-elect Gabriel Boric prepares to assume office in March, environmental and social justice are top of mind. “To destroy the world is to destroy ourselves,” he told a crowd of supporters after clinching the presidency late in December. “We don’t want more sacrifice zones, we don’t want projects that destroy our country, destroy communities.”

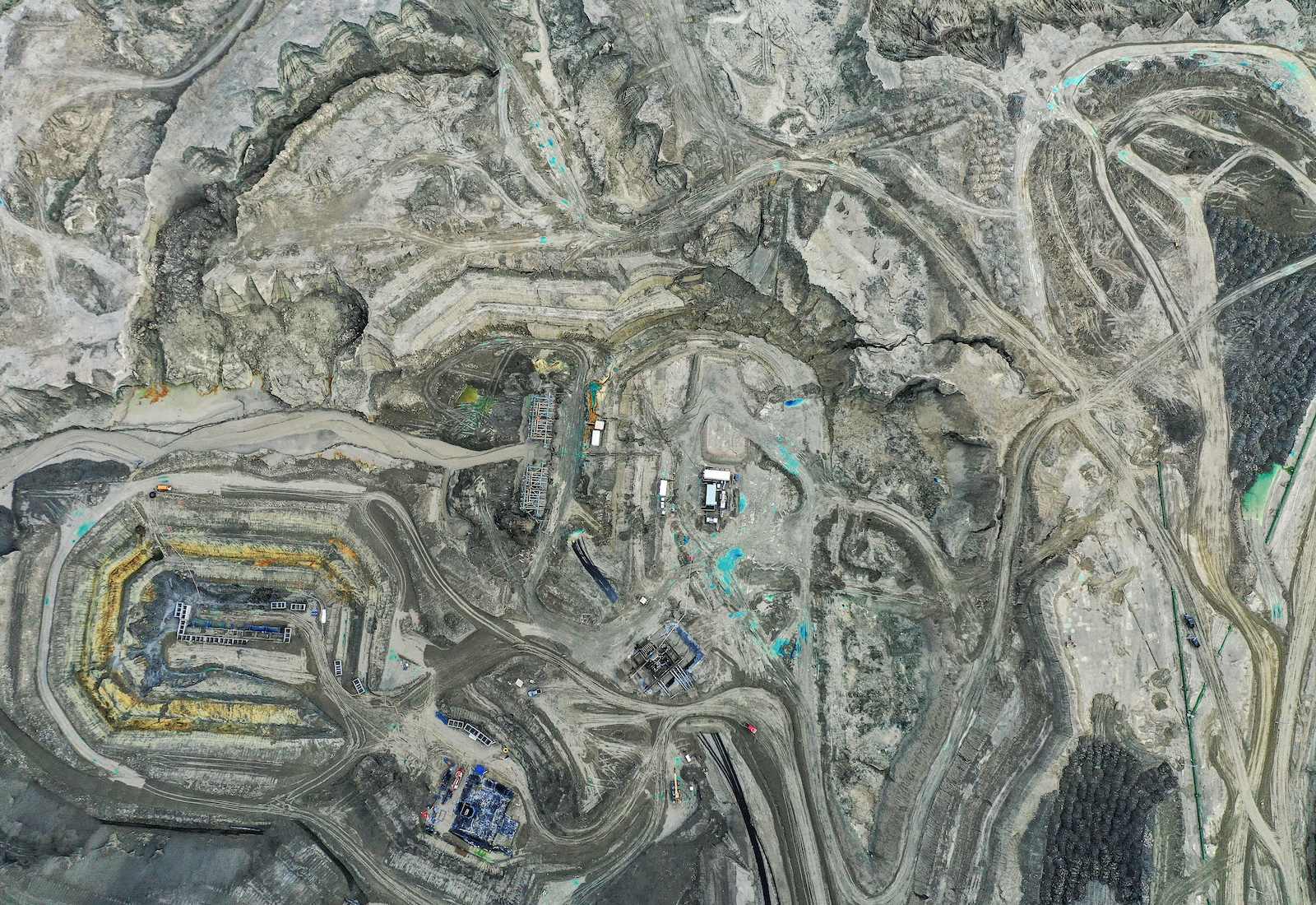

In that speech, Boric promised to oppose a controversial copper mining project called Dominga, which environmental advocates say could jeopardize a biodiverse coastal ecosystem. But his comments represent a growing desire among environmental advocates to rein in the mining industry’s abuses, from its Indigenous rights violations to environmental degradation, at a moment when demand for minerals is skyrocketing. Countries seeking to transition away from fossil fuels are clamoring for metals like lithium, copper, nickel, and cobalt — all of which are essential components of batteries, especially for electric vehicles.

Chile, already suffering from the effects of climate change, is rich in both lithium and copper; it stands to benefit from the energy transition in more than one way. But Chileans also intimately understand the costs of mining — and want to mitigate its social and environmental harms. As it waits for Boric to take office, Chile is in the process of rewriting its constitution. Since July of last year, 155 delegates have been drafting the country’s foundational laws, reimagining Chile’s identity, its form of government, and its relationship to nature. Experts say there are two major ways the delegates could protect people and the environment from the harms of mining — and set an example for other countries rich in clean energy minerals.

“I’m very excited to see what’s going to come out of this,” said Viviana Herrera, interim Latin America program coordinator for the nonprofit MiningWatch Canada, emphasizing the urgency with which change is needed.

First, many observers are hopeful that the 155 constituyentes, as Herrera called them in Spanish, will formally recognize the rights of nature, putting forests, rivers, and other natural entities on equal legal footing with humans. According to Herrera, such a recognition would make it easier for the Chilean government to protect the sanctity of the country’s wetlands and salt flats — where most of Chile’s lithium is extracted — either by banning mining in the most sensitive areas or by imposing much stricter environmental regulations.

Thea Riofrancos, an associate professor of political science* at Providence College who focuses on resource extraction in Latin America, gave the example of saltwater brine, from which lithium is extracted. Recognizing nature’s legal rights, she said, could spur changes to the way the government regulates brine — not purely as an economic asset, but as a life-giving ecological resource.

“We shouldn’t just think of the strategic value” of brine, Riofrancos said. Rather, “we should also think about what nature can bear … and the nonhuman species which depend on that brine,” which include shrimp and the flamingos that eat them. These considerations could empower government agencies to require more environmental consideration from mining companies.

There’s precedent for this kind of policy. In the 2008 Ecuadorian constitution, “Pachamama” — an Indigenous name for Mother Earth — was given the right to exist and to “maintain and regenerate its cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes.” And these rights have been effective. Last year, the country’s Constitutional court forced the Ecuadorian government to revoke mining permits for two companies after ruling that their operations in a protected part of the Amazon rainforest violated the rights of nature.

“[T]he risk in this case is not necessarily related to human beings … but to the extinction of species, the destruction of ecosystems, or the permanent alteration of natural cycles,” one of the court’s judges wrote in the majority opinion.

Chile would be the world’s second nation to enshrine the rights of nature into its constitution. But several other states and countries — in Bolivia, Mexico, Pakistan, and India, to name a few — have recognized them in national laws and judicial decisions.

Mining doesn’t only harm nature; it can also be catastrophic for people who live near mineral deposits. According to James Blair, an assistant professor of geography and anthropology at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, Chile urgently needs to adopt a regulatory framework capable of protecting Indigenous peoples from the multinational mining companies that so often exploit them. This could start by protecting Indigenous peoples’ right to “free, prior, and informed consent,” or FPIC, the right to be consulted on mining decisions that may impact their way of life.

This concept has already been laid out in international frameworks like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Labour Organization’s 1989 convention on Indigenous and tribal peoples — both of which Chile ratified more than a decade ago — but the agreements are hard to enforce, and violations have remained common. In a 2018 stakeholder report to the United Nations, the nonprofit Cultural Survival noted that Indigenous communities in Chile “continue to be excluded from decision-making processes for the use of their ancestral lands.” It specifically called out the Chilean government for failing to protect communities from extractive industries such as mining. Currently, the country’s laws only require mining companies to engage in “good faith” consultation with Indigenous peoples in some circumstances, and even then they are not required to reach an agreement.

According to Kate Finn, executive director of First Peoples Worldwide, this is a common problem. What mining companies call free, prior, and informed consent often amounts to little more than information sharing, with Indigenous peoples merely given warning that a project will be undertaken — whether they like it or not. “They do not leave room to integrate the actual perspectives and priorities of Indigenous peoples,” Finn said. “There must be an informed process … for Indigenous peoples to say yes or no to mining that impacts their territories.”

It’s unclear whether stronger FPIC protections will be on the table as Chile rewrites its constitution, but — as with the rights of nature — there’s precedent to do so. Recognition of Indigenous peoples’ right to FPIC has been constitutionally enshrined in the Philippines since 1997, when the state began requiring FPIC “prior to the grant of any license, lease, or permit for the exploitation of natural resources.” And in Peru, even though FPIC is not constitutionally recognized, it’s recognized by a landmark law from 2011.

Of course, laws and constitutional provisions aren’t bullet-proof; violations of FPIC requirements are common even in Peru and the Philippines. This is one reason why many environmental advocates stress that a holistic solution to the harms of resource extraction must involve efforts far beyond the borders of mineral-rich countries like Chile — global efforts to reduce the demand for metals in the first place.

These efforts could include scaling up recycling infrastructure for battery materials — a strategy that the government and private companies could jointly pursue, especially in wealthy Western countries like the United States. According to a report prepared last year for Earthworks by the University of Technology Sydney, better recycling could reduce demand for raw metals like copper by up to 55 percent by 2040. Better technologies could also extend batteries’ lifetimes so they don’t need to be replaced as often, and the increased development of “reuse markets” could do even more to extend their usefulness. For example, making spent car batteries available for grid storage could add another 12 years to their lives.

On a more systemic level, Payal Sampat, mining program director for the nonprofit Earthworks, called for global efforts to reduce demand for batteries — and the metals required to make them — by disincentivizing private car ownership. Housing reform and increased investment in public transportation, for instance, could make it easier to get by without a private vehicle, and could help blunt the international appetite for hard-to-get materials like lithium.

Herrera agreed. “This is something we need to be thinking about here in countries such as Canada or the U.S,” she said. While wealthy countries celebrate sales increases and enact tax incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles, the picture looks different to those affected by mining. “They see destruction, they see sadness in those electric cars,” Herrera said, even as she acknowledged the devastation that developing countries will suffer from climate change if the world fails to decarbonize quickly enough.

For now, Herrera’s eyes are trained on the Chilean constitutional convention and on President-elect Boric. There’s no guarantee that new FPIC and rights of nature provisions will be codified into the nation’s foundational laws, but the constituyentes have opened up an important dialogue that could begin to address mounting concerns from the country’s environmental groups and Indigenous peoples. “They have huge hopes that the system that created this inequality within Chile is going to change,” she said.

*Correction: This story originally misstated Thea Riofrancos’ position.