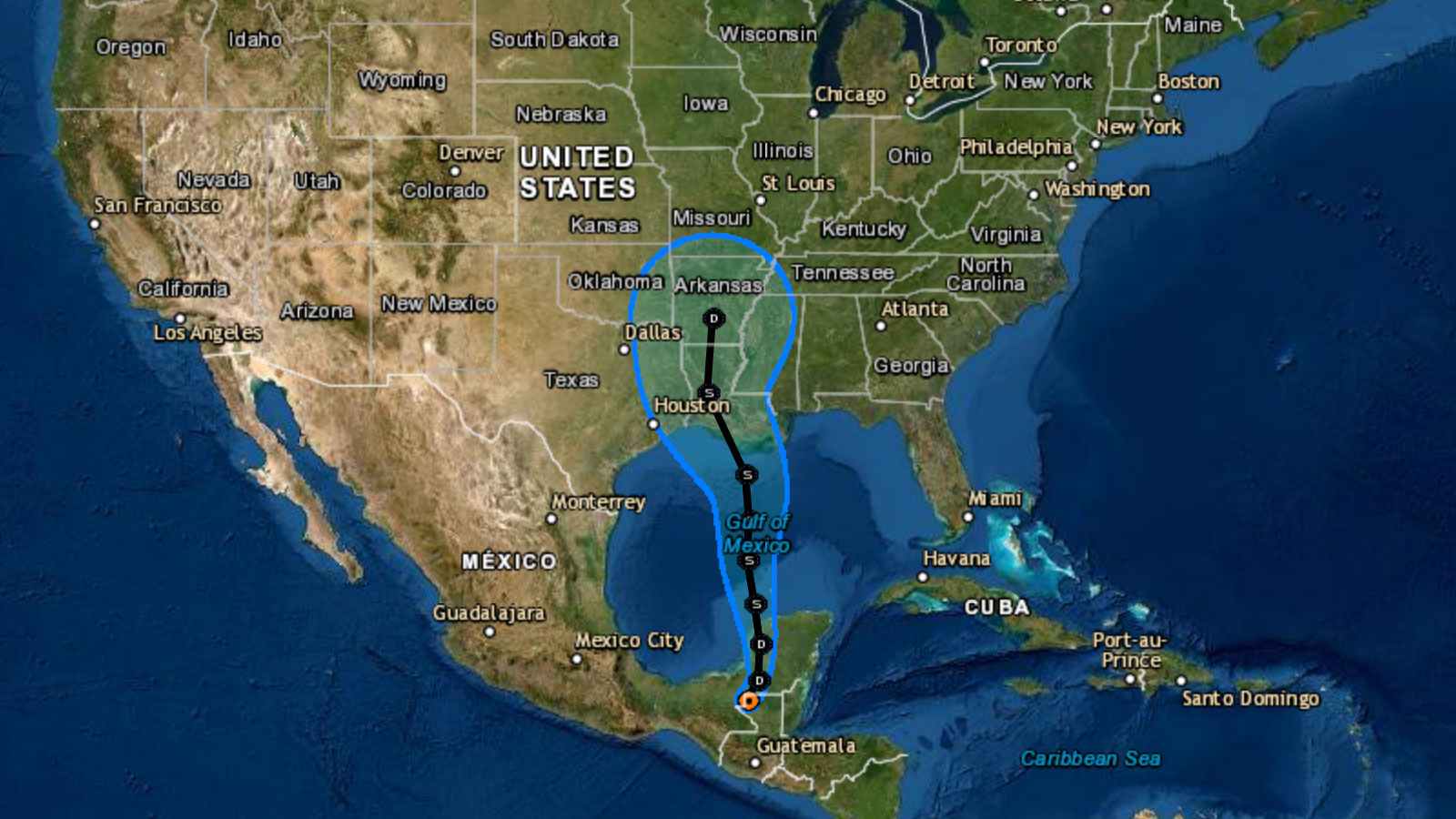

As you read this, the third named storm of the Atlantic hurricane season, which officially started on June 1, is churning its way across southern Mexico. Meteorologists expect it to soon head northward, where it could gather strength over the warm, open waters of the Gulf of Mexico. It’s unlikely that Cristobal will turn into a full-blown hurricane, but experts say it’s likely that the storm will slam into the Gulf Coast late this weekend or early next week.

Cristobal developed winds greater than 39miles per hour, the minimum for a named storm, on Tuesday — one day after the official start of the hurricane season. If that feels a bit early for the third named storm of the season to rear its head, that’s because it is. For the past six years straight, a named tropical storm has appeared in May, days or weeks ahead of the official start date. But the Atlantic doesn’t usually spawn so many powerful storms so fast: This is the first time the third named storm of the Atlantic season has arrived so early.

In 2019, the third named storm of the season arrived on August 20. That’s due in part to the fact that last year had an El Niño, a wind pattern that blows warm air into the Pacific Ocean and sucks cold water into the Atlantic, helping to suppress storms there. This year looks like it could develop into a La Niña year, when the opposite weather pattern occurs, creating conditions for more hurricanes to develop in the Atlantic Ocean. Ocean water warmed by rising global temperatures (read: climate change) in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea also contributes to the likelihood of an unusually active hurricane season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s annual hurricane forecast predicts between 13 and 19 named storms including six to 10 hurricanes (compared to the average six).

“In modern history, this is unusual from the standpoint that you typically see the third storm in August,” Dan Kottlowski, AccuWeather’s lead hurricane expert, told Grist. Warm water, he said, is the main culprit. “You only have to take the temperature up maybe a half a degree Celsius for it to be more optimal for storm development.” Kottlowski said ocean surface temperatures in the Atlantic have risen since 1995, something he attributes in part to the way the ocean naturally cycles water but is also tied to rising global temperatures in recent years.

Right now, Kottlowski expects Cristobal to move through the western portion of the Yucatán over the next day or so, move off the west coast of the Yucatán, and then track toward the center of the Gulf, making landfall somewhere along the Louisiana coast late Sunday. While it’s more likely that Cristobal will make landfall as a strong tropical storm than a hurricane, Kottlowski says flooding will be widespread. “It’s very possible storm surge values could be well above three feet, perhaps as high as six feet, from this storm,” he said. “That will be enough to inundate a good part of the coastal area of Louisiana.” Flooding could penetrate deep into the state, he said, hitting areas that were flooded last year during Hurricane Barry.

When hurricanes hit coastal states frequently affected by extreme weather, communities of color and low-income neighborhoods — often situated in low-lying areas with aging infrastructure — suffer most. Louisiana is no exception. After Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast in 2005, black residents of New Orleans and the surrounding areas were far more likely than whites to say they experienced 7 out of 10 hurricane-related hardships.

John Morales, a weather reporter and meteorologist for NBC6 in Miami who frequently highlights the connection between hurricanes and climate change for his viewers, says he is troubled by recent research that shows a statistically significant increase in the proportion of tropical storms that become major hurricanes globally. “We do know that out of the hurricanes that are forming, a greater percentage of these are becoming category 3, 4, and 5,” Morales said. He recalls the 28-storm 2005 hurricane season, when forecasters ran out of names for storms and had to start pulling letters from the Greek alphabet. “By the end of that hurricane season I was exhausted,” he said. “To think that, right now, we might be dealing with 20 storms, that is a significantly active hurricane season — it’s going to be really exhausting.”