The apple trees looked half-dead. They formed a neat line in a scrubby lot on a quiet neighborhood street. I felt compelled to pat their scrawny trunks and say, “It’s going to be OK.” The bare branches shook in the hard wind — a reminder that this bleak Sunday morning was one I’d have otherwise spent on the couch, rather than venture into the misery that is Milwaukee in late February. Yet, there I was in that frigid, dreary, windblown urban orchard because late winter is an excellent time to prune fruit trees.

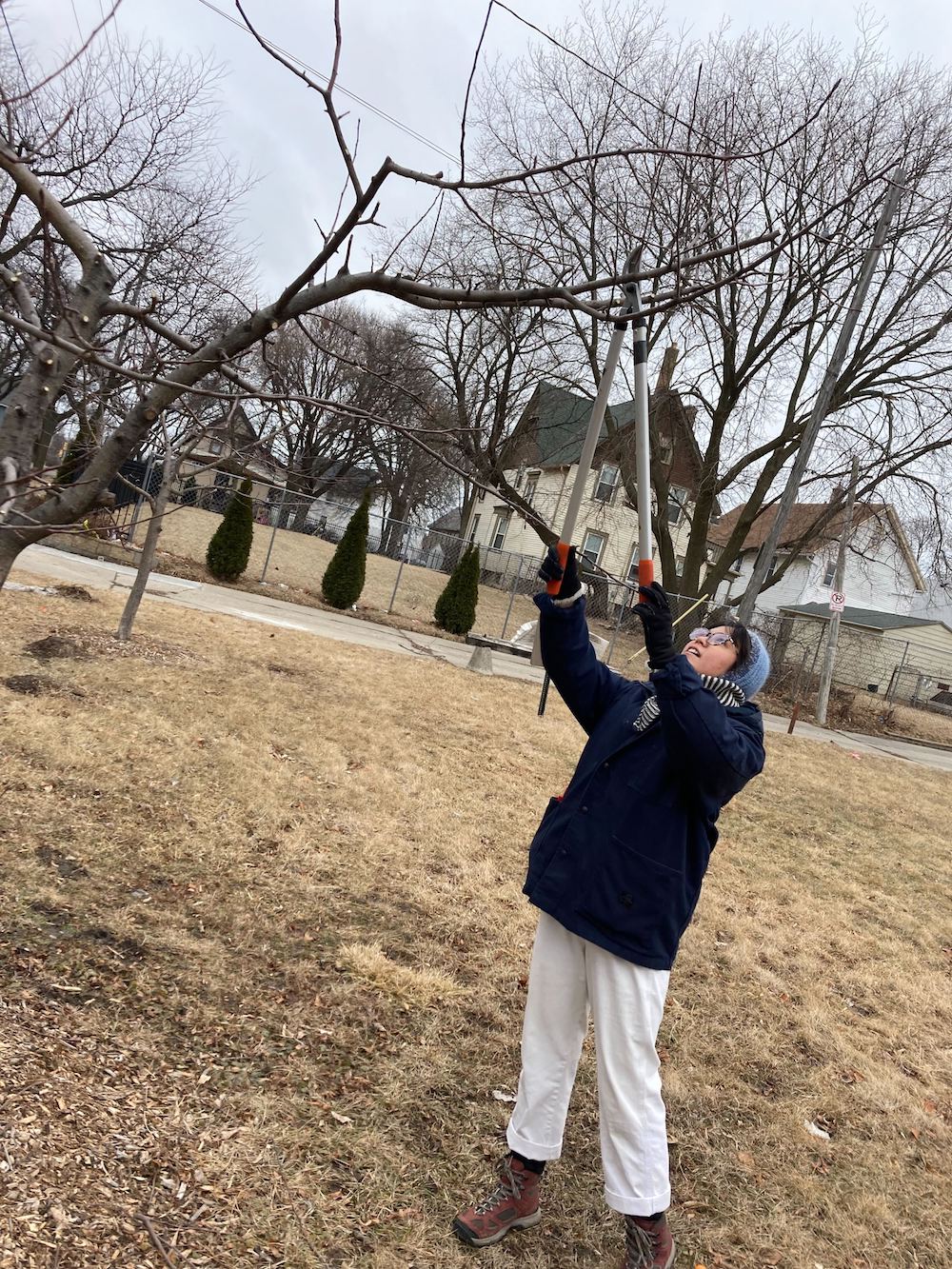

My instructions arrived the night before. “Wear plenty of clothes,” texted Jan Carroll, my pruning teacher, a retired-nurse-turned-arborist. I layered like my life depended on it: two pairs of socks and leggings, a t-shirt and flannel shirt, wool sweater, overalls, puffer coat, canvas jacket, and shearling gloves. Carroll eyed my uniform approvingly, although she kept a bag of mittens and hats in the trunk, just in case a volunteer arrived under-dressed.

Late winter is the best time to prune because trees are still dormant and won’t feel the cuts. By spring, they will have hopefully forgotten that you’ve lopped off their branches and won’t try to replace them, instead using their energy for things like growing flowers and fruit. So I sharpened my shears, and from February through April this year, met Carroll at orchards across the city to prune.

Milwaukee’s orchards began filling vacant lots around six or seven years ago in a burst of urban agricultural activity. There are orchards with as many as 30 trees, others as few as six. There’s an orchard where each tree is dedicated to a child lost to gun violence, each possessing a plaque bearing their name. The trees represent efforts from a mix of nonprofits and city and county programs to beautify green spaces and develop local food systems in neighborhoods with limited access to grocery stores.

The groups planted more than 1,500 apple, pear, plum, and cherry trees, with the understanding that community partners, schools, and churches would care for them. But many people lost interest or underestimated the work, said Carroll, an avid gardener who’d been involved as a volunteer with the prominent local nonprofit Growing Power. If not for her efforts, the trees I visited would have mostly been abandoned.

Despite growing evidence that tree-planting campaigns aren’t very effective, planting trees remains extremely popular. Take, for example, the tree pledges that inevitably crop up before Arbor Day — the last Friday of April — each year: Sony’s PlayStation recently promised to plant up to 288,000 trees. Soon after, Williams-Sonoma made a 6-million-tree pledge. From what I’ve seen, planting is the easy part. If we want to take advantage of all that trees have to offer, we’ll have to work for it.

After Growing Power shut down in 2017, Carroll, who would soon retire from a 30-year-long career as an OB/GYN nurse, identified the “orphaned” orchards and began caring for them herself, learning how to prune through YouTube, an extension class, and frequent calls to local fruit-farming gurus. She jokes that she’s a sheepdog: Whether helping deliver babies or tending trees, she loves to be of use. “It’s not like trees are namby pamby babies,” Carroll said. They can grow on their own. But if you want them to produce fruit — good fruit — they need attention. Pruning thins and shapes the canopy so that each blossom gets plenty of air and light. Without it, trees become damp and dark, leaving fruit vulnerable to pests.

The plight of Milwaukee’s fruit trees is a common story: Trees get planted, but few resources are dedicated to caring for them, so they’re often neglected. “When I met Jan and saw the work she was doing — before that, I had no idea that this was a need,” said Samson Srok, the green space coordinator at the environmental nonprofit Groundwork Milwaukee, which has begun partnering with Carroll on pruning workshops. “Tree care takes skill that takes time and effort to learn, and then years of practice until you really know what you’re doing. Folks don’t have that realization when they’re planting trees.”

City trees offer many benefits. They suck carbon dioxide from the air and lock it in their trunks and roots. They provide shade and moisture, keeping cities cool, and their roots capture runaway stormwater, which erodes and pollutes waterways. Trees boost air quality, and even foster people’s emotional health and well-being.

That’s a lot to ask of trees that don’t get much in return. Ryan Murphy, an urban forestry researcher at the University of Minnesota, said cash-strapped cities rarely have the budget to properly care for trees. With invasive pests like emerald ash borer decimating urban forests, “a lot of their resources are just going to maintaining or to removing trees in the mature canopy,” he said.

That leaves little attention for young trees, whose early years are critical. At that age, they can be coaxed into shapes that will sustain mature canopies later in life. The same thing plays out at a residential level, where trees are rarely watered after they’re planted. “It’s surprising how many people think that you can just plant a tree and walk away,” said Gillian Hodler, the community engagement coordinator at the Austin-based organization TreeFolks, which gives away trees and leads reforestation efforts. TreeFolks estimates survival rates for the trees they give away range from 40 to 60 percent.

The fact is, it’s not easy being a city tree. Many are grown in fields or nurseries before they’re uprooted for a move to the big city — a shocking experience. Dangers lurk at every street corner. There’s drought, debris, road salt, poor soil, and dirty air. There are errant lawnmowers, reckless drivers, hungry deer and mice.

So, how can you improve a tree’s odds of survival? It starts at planting. “They say you can take a $1 tree, and if you put it in a $5 hole, you will have a beautiful tree,” Carroll said at a pruning workshop I attended. On the other hand, plop a $5 tree in a $1 hole, and you will get a sad stick. Countless trees have been crippled by a bad hole. Maybe it was too shallow or skinny, or the tree was planted too deep, which cuts off its air supply. For container-grown trees, roots need to be spread out before they’re planted. Failing to do so with maple trees has led to an epidemic of stem-girdling roots, which encircle and strangle the trunk, forcing people to remove afflicted maples before they fall. “These corrections don’t take that much time,” Murphy said. “We’re talking about half the tree’s life that you could extend just by a couple minutes right at planting.”

Cities should also consider what kind of trees they’re planting. Certain species go in vogue for their canopies or fall colors. But diversity is crucial. Prized for its stately canopy, the American elm was overplanted, only to be wiped out by Dutch elm disease. Then ash trees got popular, and the same story is playing out with the emerald ash borer. “We’re learning that a diversified urban forest is critical not just for canopy coverage, but also the budgets and the finances inherent in an urban forest program,” Murphy said.

And, there’s the matter of where the trees go. Across the U.S., lack of tree cover often mirrors race and income. One recent survey found neighborhoods where residents are mostly people of color have, on average, 33 percent less tree canopy than mostly white neighborhoods. Neighborhoods where 90 percent or more residents live in poverty have 65 percent less tree cover than their wealthier counterparts. This has established a patchwork of urban heat islands, where residents experience extreme heat trapped by concrete and asphalt.

In Milwaukee, most of the trees that Carroll tends to are in the north side’s mostly Black and low-income neighborhoods, a five- or 10-minute drive away from her home in Riverwest. Carroll fastidiously maintains the orchards’ appearances. She piles mulch obtained from the city around each tree, removes the dead and dying trees, and swaddles the skinniest trunks with netting to shield them from weed whackers. “If it looks like a trashy, overgrown mess, that is how people will treat it,” she said. “Anytime you can show people that this dinky, scrawny tree is somebody’s pride and joy, you will come out better for it.”

Pruning makes the trees look more orderly, too. But really, the idea is to organize a tree, encouraging it to funnel its energy into the most productive branches. There are basic rules. Remove the broken, damaged branches. Snip the shoots going straight up — they can’t support the weight of fruit. Don’t let arms criss-cross because they’ll shade each other out. But plenty of limbs don’t fall into these neat categories.

Starting out, I hesitated before making cuts. I walked circles around each tree, sometimes carving a path through the snow, surveying a branch from all sides: What looks crooked from one angle seems straight from another. The stakes feel high when you’re cutting into a living thing. I frequently consulted Carroll, who would wander over in her bright blue coat and surprise me by taking off more than I’d dared. She taught me to consider the trajectory of each branch and picture how it might grow over the next year — a puzzle of both space and time. Each pruner has their own style; hers is aggressive. When you’re done, she told me, “you should be able to throw a cat through the branches.”

Everywhere we went, someone in the neighborhood stopped to say hi to Carroll. Others paused on their brisk morning walks to look curiously at our crew, which had grown to three volunteers. Pruning tends to look like something one shouldn’t be doing in public, whether you’re waving a branch-cutter overhead or wobbling on a step ladder, sawing off the top of a tree. After each session, we piled the shorn branches neatly by the sidewalk. (Carroll has a friend who would swing by later, picking them up to feed his goats.)

Pruning soon altered the way I saw trees in the city. I pitied the overgrown ones, so clearly in want of a good trim. Hodler, the TreeFolks coordinator, had told me there were volunteers who enjoyed the work so much they’d been coming for 30 years. “It’s really addictive to have the feeling that you did something tangible that you know has a real effect in the world,” she said. I could appreciate that, after knowing the satisfaction of an array of tidied trees.

Many cities have volunteers and nonprofits caring for their urban forests. Trees New York, which was founded in response to cutbacks in the city’s budget for tree care, has trained a legion of citizen pruners. Similar programs can be found in Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, and the Twin Cities. Samson Srok, from Groundwork Milwaukee, says the prevalence of abandoned trees makes sense, considering the heavy reliance on volunteers. “The biggest radical solution would be a reorganization of how we assign value to land and to green space work as a whole,” Srok said.

Even the best intentions sometimes fizzle out. That’s what I observed across Milwaukee’s orchards. We picked up trash everywhere we went. Orchard signs haven’t been maintained. Plastic spacers to keep branches apart indicated someone had taken the time to insert them at one point. But they neglected to remove them, so trees swelled around the plastic like a bruise.

As cities turn more and more to trees and green infrastructure to adapt to climate change, Diane Pataki, director of Arizona State University’s school of sustainability, agrees that we need new ways to manage these resources. Trees pose a challenge because they don’t fall neatly into bureaucracy’s compartments. They provide services, but unlike pipes and gutters, they’re alive. “It’s been hard for cities to figure out a way to take care of them because they’re dynamic and they need a lot of care,” Pataki said. “They do unexpected things.”

Watching things evolve is Carroll’s favorite part of her work with the trees. As a gardener, she’d loved seeing banana peels and apple cores melt into compost. Through the orchards, she got to witness trees mature and to meet the community members transforming empty lots into spaces of abundance.

By mid-April, trees across Milwaukee had budded. On the last day of pruning, we went to an apple orchard bordered by a busy street and quiet creek. Carroll told us to avoid bumping the buds, in order not to damage the flowers that would bloom into fruit. By then, pruning had begun to feel less like doing something to the trees and more like something I offered, in the hopes that they’d produce lots of fruit, that they’d stick around for years to come.

We’d take a break for a few weeks, then meet again. Carroll said spring and summer would bring new tasks: mulching, fending off bugs. I’ll go back in the summer when I hope the branches will be draped in leaves, heavy with apples and plums. I want to see where they grow.