This story is part of Grist’s Summer Dreams arts and culture series, a weeklong exploration of how popular fiction can influence our environmental reality.

If you have warm, fuzzy memories of reading Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree growing up, re-reading the book might be a shock.

The children’s tale begins with a happy friendship between a boy and a tree. But as the boy gets older, he outgrows climbing the tree, swinging on its branches, and munching on its apples, and the tree gets lonely in his absence. Eventually, the boy comes back wanting money, so the tree offers him its apples to sell. The tree gives away its branches so the boy, now an adult, can build a house; he later gets its permission to saw down the trunk and build a boat to sail far away. In the end, he returns as an old man and simply sits on the old stump, all that’s left of his childhood companion. “And the tree was happy,” the book concludes.

Since its publication in 1964, The Giving Tree has sold more than 10 million copies. More than half a century on, there’s a never-ending debate about the story’s meaning. Does the tale enshrine generosity, or does it warn readers about the dangers of self-sacrifice and dysfunctional relationships? Does it condone plundering the natural world, or does it offer a lesson about thoughtless extraction? In the face of warnings about climate catastrophe and the “sixth extinction,” it reads less like an innocent childhood favorite, and more like a cautionary tale.

But the book presents the story ambivalently, with no obvious moral takeaway, and that has been key to its divisiveness. Devoid of much context or setting, the book provides a “blank slate” onto which “we project what we know,” said Sarah Abbott, an associate professor of film and media at the University of Regina in Canada who has studied the book. Interpretations tend to say more about the ideas of the people who came up with them than they do about the book itself.

The Giving Tree, Abbott says, reflects a worldview that nature is here for the taking, and that it’s separate from humans, not deeply interconnected. “This point of view has gotten us to this present point in time when we’re having a climate disaster, which is only getting worse every day,” Abbott said. When people read the book, she said, their responses are split — the story either affirms the idea that nature is a means to an end, reinforcing what people have been taught, or “it repels us with disgust and horror” at the greed of modern society.

If taken at face value, The Giving Tree can reinforce a problematic mindset. But if considered critically, it provides a lens to question it. Some environmentalists may think nature is worth saving in its own right, but many are still guided by the philosophy that underlies The Giving Tree, thinking about trees mainly in terms of what services they offer. Climate advocates, for instance, have latched onto trees’ carbon-sequestering powers, hoping that planting billions and billions of them can help stabilize the climate. The idea has made its way to the international stage, with countries formally adopting tree-planting as a cornerstone of their climate policies.

There is, however, a limit to what trees can provide for us — especially if we don’t give anything in return.

There’s no question that trees have been giving and giving since long before Homo sapiens first emerged. “Humans have evolved to live with trees,” said Charles Watkins, a professor of geography at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. Around 4 million years ago, it’s believed, when changes in the climate opened stretches of grassland in formerly forested areas of Africa, early human ancestors swung down from the branches and started to travel on two feet. Trees provided more than a place to rest in the shade, or a snack in the form of fruit or nuts. They also brought technology. Their wood formed the handles of spears and bows, and roofs to keep out the rain. Our ancestors burned their branches to make fire, a pivotal part of human evolution. “It’s difficult, really, to think of something which they don’t provide,” Watkins said.

Throughout history, trees have also served as sacred cultural touchstones, and landmarks that oriented people to the landscape. In Japan, ancient folklore holds that spirits called kodama inhabit trees that grow to be a century old; in ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder wrote that “trees and forests were supposed to be the supreme gift bestowed” by nature on humankind. Trees capture our imagination mainly because of their age, Watkins said — old, gnarled ones are seen as witnesses to history.

Today, the way people think about the benefits of trees has changed. Sure, they still provide shelter, having been sawed and hammered into the boxy shapes of homes, furnished with wooden beds, desks, cabinets, and more. But their invisible advantages are starting to get more attention, from the health benefits of walking through the woods to their ability to absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas behind climate change. About 20 years ago or so, Watkins planted a small, three-acre woods. “Carbon sequestration was the last thing on my mind,” he said. “I wanted to grow trees for nature conservation, for beauty and whatever, but now 25 years on, I look at these trees and I think, ‘Wow, look at all that carbon that’s being sequestered!’”

It wasn’t a new discovery, exactly — tree-planting has long been seen as a way to address the climate crisis, playing a role as far back as the 1992 Kyoto Protocol, an international attempt to address global warming. But the scale of ambition has grown. The Billion Tree Campaign, started by the United Nations Environment Program in 2006, achieved its goal the following year. The objective then blossomed to planting 7 billion trees, accomplished in 2009. Five billion tree-plantings later, in 2011, the U.N. handed off its tree project to a nonprofit that raised the bar to a trillion.

In recent years, large-scale tree-planting has turned into the rare kind of climate solution that’s popular with almost everyone — it seemed to be the only thing that former President Donald Trump and Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg actually agreed on. And countries around the world have formally adopted the strategy, with global initiatives multiplying. The United States joined the One Trillion Trees Initiative by the World Economic Forum last year; India has pledged to cover a third of its land area in forest; the African-led Great Green Wall movement seeks to grow trees across the entire width of Africa on the Sahara’s southern edge. Even Saudi Arabia has an environmental initiative to plant 10 million trees by the end of this year. Businesses have gotten on board with tree-planting initiatives too, from the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to Salesforce and Mastercard.

But experts have urged caution about massive tree-planting as a climate solution, especially planting trees where they weren’t before. When a 2019 study suggested that a massive, global tree-planting effort could capture two-thirds of the atmospheric carbon dioxide humans have emitted since the Industrial Revolution, for example, the backlash was swift, with scientists calling the calculations “misleading” and “shockingly bad.”

“It’s a fantasy,” said Chris Still, a professor of forestry at Oregon State University, who helped write a critique of the study. “It’s a possible solution for part of the problem. I don’t want to pour water on the idea entirely, but it’s a small piece of what needs to be done.” There’s growing evidence that the effects of climate change are inhibiting forests’ potential to sequester carbon, with trees going up in flames, withering in drought, and succumbing to pests with expanding territories. Trees, it turns out, can’t solve all our problems; they’re more like a Band-Aid.

So why are people so captivated by the idea? For one, trees are charming — they’re sort of the polar bears and whales of the plant world. But more importantly, perhaps, is that planting trees seems relatively easy on the surface. Less hard, anyway, than going vegan, ditching cars for bikes, making and buying less stuff, transitioning every industry and power source to renewable energy, and all the other difficult things that would help stabilize the climate. “In some ways, it feels like it’s an easy solution to a really wicked hard problem,” Still said.

A new book similarly complicates the case for planting billions upon billions of trees. In A Trillion Trees: How We Can Reforest Our World, British journalist Fred Pearce argues that while a trillion more trees on the planet is a worthwhile goal, it should not be accomplished through a gigantic global effort specifically to plant them. “In most places, to restore the world’s forests we need to do just two things: to ensure that ownership of the world’s forests is vested in the people who live in them, and to give nature room,” Pearce writes.

Wait — give nature something? That part was not in The Giving Tree. The book depicted an imbalanced relationship: “one gives, and the other takes,” as Silverstein described it. One way to think about the book is to forgive the tree’s lack of boundaries, and to criticize the boy’s failure to provide anything in return.

“Indigenous story traditions are full of cautionary tales about the failure of gratitude,” Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, wrote in an essay about responding with reciprocity to the gifts nature provides for free — rain, honeybees, fields of flowers. “When people forget to honor the gift, the consequences are always material as well as spiritual. The spring dries up, the corn doesn’t grow, the animals do not return, and the legions of offended plants and animals and rivers rise up against the ones who neglected gratitude. The Western storytelling tradition is strangely silent on this matter, and so we find ourselves in an era when we are rightly afraid of the climate we have created.”

Kimmerer calls for healing the damage that humans have inflicted on the Earth: “We are not passive recipients of her gifts, but active participants in her well-being.” It sounds like the opposite of The Giving Tree, and it would probably make for a better ending.

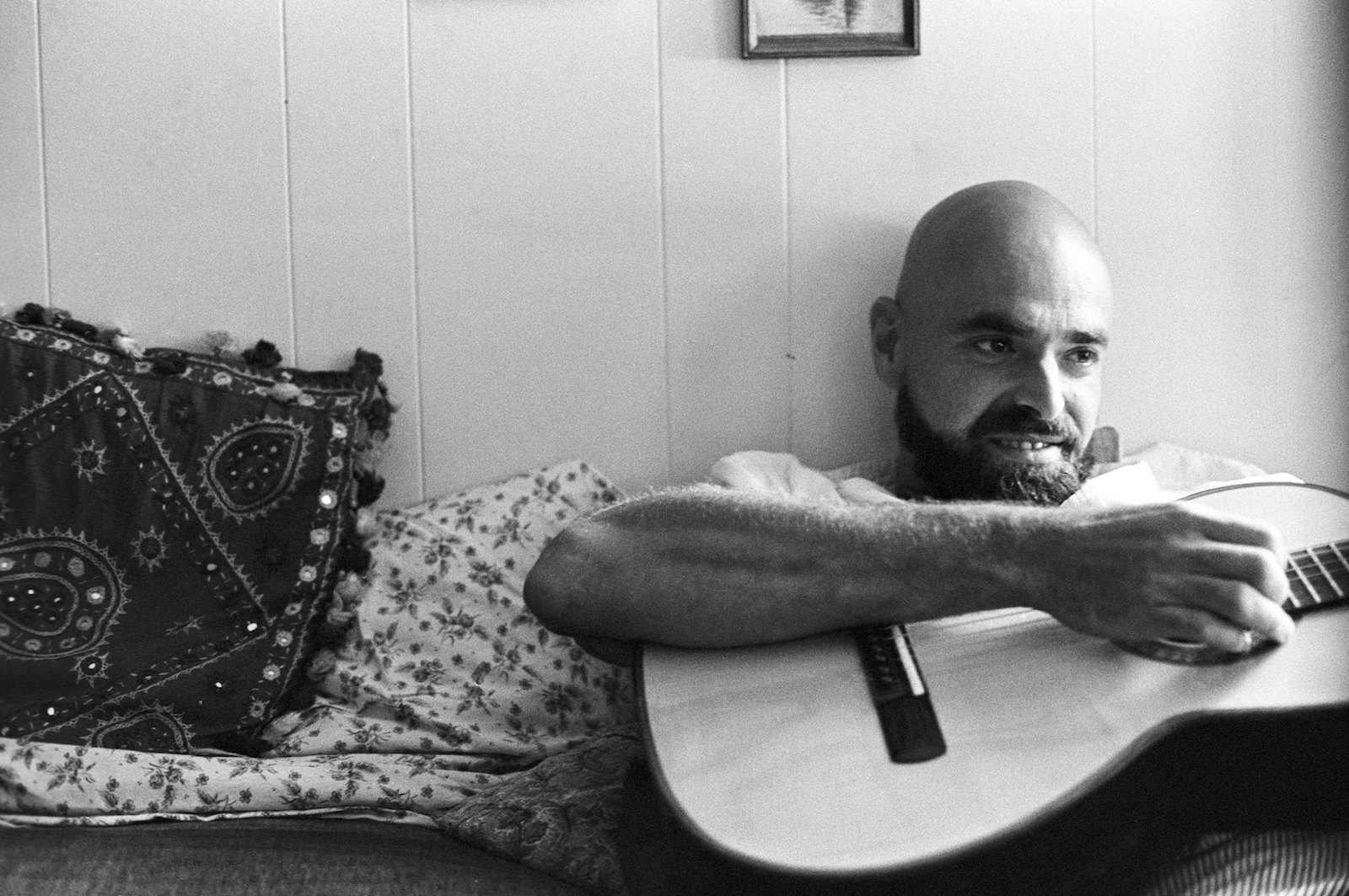

The obvious place to look for understanding The Giving Tree would be the author himself. But Silverstein was notoriously cryptic about the book’s meaning.

It’s clear that Silverstein, who grew up in Chicago in the 1930s, did not set out to write things for kids. In fact, he hated most children’s literature. To Silverstein, the classics and contemporary books alike were trash, though he had a soft spot for Dr. Suess. But as for old stand-bys like Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little — “Those damn books are so bad they’re beautiful,” he once said, according to A Boy Named Shel, a 2011 biography by Lisa Rogak. “The condescension is not only thick enough to walk on, but absolutely destructive.” So when a friend suggested he start penning picture books, he thought it was far-fetched; Silverstein was known mainly for drawing offbeat cartoons for Playboy magazine, and was a regular visitor of the Playboy Mansion.

The Giving Tree was among his earlier books for children, and it did not prove to be an easy sell. Silverstein got turned down by Simon & Schuster, where an editor told him the book was too sad for kids and too simple for adults. It found a home at Harper & Row, with a modest first printing of 7,000 copies. Sales virtually doubled every year in its first decade after publication. The book’s editor, Ursula Nordstrom, attributed this success to ministers and Sunday school teachers, who saw it as a parable about God’s unconditional love.

As the book got popular, it found many critics. Feminists hated it because the tree, painted as a “she” in the book, gets exploited and sacrifices everything; mothers hated it because they felt they were expected to be the tree. They and others viewed the book as glorifying unhealthy relationships in general. In “The Tree Who Set Healthy Boundaries,” a modern rewriting of the book by playwright Topher Payne, the tree draws the line at getting its branches cut off and confronts the boy, saying, “Okay, hold up. This is already getting out of hand.”

Silverstein wrote a book that could be about anything. The choice to depict the giver as a tree may be what left the possibilities for interpretation so wide open.

“Those of us who are shocked [when we read the book], we see the tree as the tree,” Abbott said. “Whereas people who aren’t shocked, they probably see the tree as a metaphor.”