It was late one night in January 2009, and Jonathan Epstein was standing on the roof of an abandoned storage depot near Khulna, Bangladesh, with the writer and journalist David Quammen along with a small team of veterinarians. The group was in Bangladesh on a strange errand: They were catching bats.

It had been more than a decade since the first outbreak of the Nipah virus in Malaysia. Nipah, named after the home village of one of its earliest victims, causes respiratory distress, inflammation of the brain, and seizures. Its mortality rate is staggeringly high — between 40 and 75 percent of those who contract the disease ultimately die. (The virus depicted in the now all-too-prescient 2011 film Contagion was based on Nipah.)

In Malaysia, the initial outbreak of Nipah in 1998 had infected 283 people and killed 109. Scientists eventually discovered that the virus had been passed from bats to local pig farms; the government slaughtered over 1 million pigs in an effort to stop the spread. But Nipah kept coming back, popping up in new places around the world, killing hundreds. Epstein and his colleagues were in that storage depot in Bangladesh trying to understand if the bats there were also carriers of the virus — and if they might pass it to humans again.

Epstein, a veterinarian and disease ecologist at the nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance in New York City, has been all over the world identifying and tracing viruses that could make a deadly jump from animals to humans, helped by sprawling cities, clear-cut forests, and other human encroachment into the natural world. He helped trace the first outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS, in 2003 to horseshoe bats in China; the outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS, in 2013 to camels and bats; and — when it’s safe to travel again — he will return to China to help pinpoint the source of the current coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Bats are, once again, the main suspects.

“There are always two pivotal questions,” Epstein said by phone from his home in Queens. “How did this happen? And could it happen again?”

Sixty percent of new infectious diseases — diseases that, like COVID-19, have never before reached humans — originate in domesticated animals and wildlife, often bats, rodents, or non-human primates. Scientists estimate that there are as many as 800,000 of these so-called zoonotic viruses lurking in the natural world that could infect humans. The animals carrying these viruses often don’t get sick; instead, they serve as “reservoirs,” amassing pathogens as they eat, sleep, and socialize. It’s a good deal for the viruses: They get a free ride, while they wait for a chance to make a cross-species leap.

The problem is that those deadly leaps are becoming more common. Population growth and environmental and habitat destruction are bringing humans into more frequent contact with certain species — and the viruses that they carry.

“Every future viral threat that people could get already exists and is circulating in those animals — always has been,” said Dennis Carroll, an expert on zoonotic infectious diseases and the former head of the emerging threats division of the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID. “It’s just that now we’re bumping into them with a frequency that enables spillover to occur.”

As COVID-19 spreads across the globe, infecting almost 3 million people worldwide and killing over 200,000, public health officials, policymakers, and journalists are analyzing what went wrong. Why was the world so unprepared? Should countries have higher national stockpiles of ventilators, masks, ICU beds? Should stay-at-home orders have been issued earlier?

These are all measures for after an epidemic has begun, after an enterprising virus has leapt from an animal to a human (a phenomenon scientists call “spillover”). But a small group of ecologists, epidemiologists, and veterinarians have spent the last decade attacking pandemics from another angle. Epstein and other researchers have been out in the field, testing bats in Bangladesh and pigs in West Africa, trying to catalog a huge number of viruses in the hopes of preventing a spillover into human populations. Because there’s no outbreak if the virus never makes the jump.

PREDICT team members sample wildlife in the field in Sierra Leone. Courtesy of Simon Townsley / PREDICT

In 2005, a strain of avian influenza called the H5N1 virus began spreading across Southeast Asia towards Eastern Europe. The disease was rare, but it could be fatal: Roughly 60 percent of those infected died. Experts were concerned that they could be looking at a “potentially historic event.”

At the time, Carroll was at USAID as a senior infectious disease specialist working on the organization’s response. His focus was on malaria and tuberculosis, diseases that are well-known — if not well-managed — everywhere in the world. Luckily, H5N1 did not turn into a global pandemic, but the experience changed Carroll’s perspective on the risks. In the 1960s, there were a few hundred million poultry produced in China; by the 2000s, when the country’s population had nearly doubled, China was producing billions of chickens, ducks, and turkeys every year. Carroll realized that as the human population grew, so would the odds of a deadly pandemic. “It was really a profound eye-opener for me,” he said.

Carroll suspected that there were many more viruses like the avian flu lying in wait, looking for a chance to make the jump to humans. But at the time, there was little understanding of how many dangerous viral illnesses existed. “It was an open question of what the ‘viral dark matter’ circulating in wildlife was,” he said. “Are we talking about a hundred viruses? Or something different?”

That question became the basis of PREDICT, a kind of catch-and-release project for viruses that Carroll championed from within USAID. The program, launched in 2009, included scientists and researchers from the University of California, Davis and EcoHealth Alliance — all with the singular goal of discovering new viruses before they spill over into people.

Global Health Program workers sample a bumble bee bat in Kjwe Min Gu Cave in Myanmar. Courtesy PREDICT

It was an enormous undertaking. With an annual budget of around $20 million, researchers identified potential viral “hotspots” around the world, contacted local governments, and surveyed key species that could be carrying novel diseases. They also began training locals in more than 30 countries around the world, including in Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Bangladesh. On-the-ground experts like Epstein, the wildlife veterinarian, taught locals to capture animals, take blood samples to test for novel viruses, and release them back into the wild.

“It’s really grunt work,” Carroll said. “This is not a technological challenge. You go out and capture bats, you go out and capture rodents.”

Based on PREDICT’s early work, Carroll and other researchers estimated that there are around 1.67 million yet-undiscovered viruses circulating in mammals and birds, the animals most likely to transmit disease to humans. Of those, between 631,000 and 827,000 have the potential to make the leap to humans.

The good news is that the proportion of those 600,000-plus viruses that could cause serious illness is very small. “Most microbial infections in people are inconsequential,” Carroll said. “They don’t have adverse effects.” So researchers don’t need to worry about all potentially zoonotic viruses — just the ones that could turn deadly.

Jonna Mazet, the organization’s global director from its inception until last year, said that PREDICT and its collaborators collected 168,000 samples from people and animals and identified more than 900 new viruses. Of those, 160 were coronaviruses — in the same family as SARS-CoV-2.

But sampling animals by climbing through trees, setting up nets on warehouse roofs, and crawling into bat-infested caves was only part of the challenge. There are about as many pathways for transmission as there are viruses. And so the group wasn’t only cataloging potential diseases. They were also searching for hidden patterns, looking for the unexpected risky behaviors that could allow a virus to spill over into humans.

The first case of the global Ebola outbreak in 2013 was traced to a toddler in the West African country of Guinea, who had been playing under a tree housing a family of bats, likely displaced by the destruction of surrounding forests by foreign mining and timber companies. (Scientists still aren’t sure exactly how close contact with those bats led to the child getting infected). In Malaysia, the first outbreak of Nipah was linked to pigs that had eaten pieces of fruit dropped by nearby bats and then spread the disease throughout industrial pig farms.

Red Cross workers in Guinea carry the body of an Ebola victim in a cemetery in 2014. Kristin Palitza / Getty Images)

But some types of spillover are known, common, and preventable. “Let’s take, for example, live animal markets,” Epstein said. “People are still bringing wild animals, particularly bats, rodents, and non-human primates, from their natural environment into urban settings. These species not only have contact with each other, under very stressful and unhygienic conditions where there’s opportunity to trade viruses, but they’re also being handled and butchered by people.”

That close contact provides an opportunity for people to become exposed. The SARS outbreak in 2003 likely originated from a wildlife market in the Chinese province of Guangdong. And the suspected source of the novel coronavirus currently gripping the planet is a market in Wuhan.

Epstein explained that certain interventions — making wildlife markets more hygienic, or preventing wild animals from being sold at all — could dramatically lower the possibility of spillover. But he emphasized that the work has to be done in a culturally sensitive way, by building local partnerships. “This isn’t about a group of Westerners imposing their idea of what’s safe on cultures that have been doing something for generations,” he said.

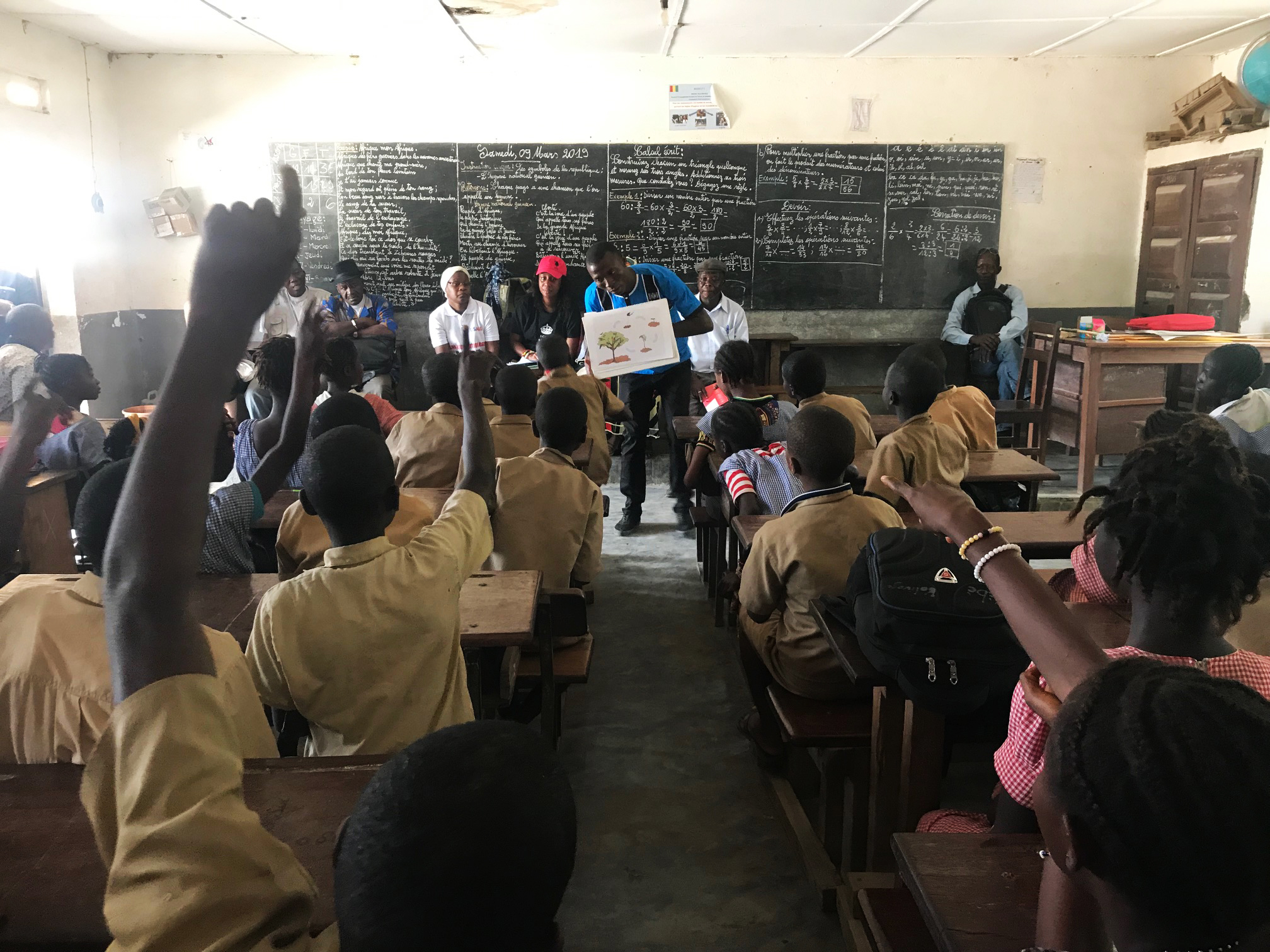

Students in Guinea listen to a school presentation on living safely with bats. Courtesy of PREDICT

Some have taken a harder line. The World Conservation Society has called for a global ban on the trade of wildlife, citing pandemic risks. Anthony Fauci, the United States’ top infectious disease specialist, told Fox News that the Chinese government should immediately ban so-called “wet markets.” “It boggles my mind how, when we have so many diseases that emanate out of that unusual human-animal interface, that we just don’t shut it down,” he said.

Trading wildlife is only one of many human behaviors that can set off a spillover. When Epstein and colleagues were on the roof of that storage depot in Bangladesh, they were studying another outbreak of Nipah, one that appeared to be passed to humans when they ate sap from date palm trees. Locals collected the sap in small clay pots, tapped to the palms and left open to the air — and to any fruit bats that might want to take a sip.

That was the immediate cause of the outbreak: sap contaminated by bat urine and feces. But for Epstein and other scientists, the lesson was much larger. Mowing down forests for large-scale agriculture, harvesting timber, and sprawling cities — all these activities were forcing bats into close quarters with people. “It’s not the animals’ fault for carrying these diseases,” he said. “These are things that we do to the environment around us.”

Over the past century, the human population has exploded. At the height of the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic, the global population was around 1.8 billion, less than a quarter of what it is today. In the past century, millions of humans have spent years slaughtering wildlife; cutting down trees; placing cows, chickens, and pigs in close contact with wild animals — providing ample opportunity for viruses to make a deadly leap.

Even in the face of enormous environmental changes, Epstein and other scientists are convinced that it wouldn’t take much to make a big difference, whether it’s shuttering wildlife markets or bat-proofing pots for date-palm sap with a small screen. “These are wholly human-made, human-driven events, and knowing that is hopeful, because we can actually focus on changing the way we do things,” Epstein said. “These pandemics are preventable.”

A red-tailed guenon in Uganda chews on an oral swab rope—a noninvasive sampling technique used by scientists studying zoonotic diseases. Tierra Smiley Evans / UC Davis

Last September, the PREDICT program ran out of money. It had passed through two five-year funding cycles but wasn’t renewed by USAID.

Some of those involved were deeply disappointed. “It was a genius, visionary program that USAID took a big risk to fund, and it’s a crying shame it was canceled,” Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, told the Guardian.

Contrary to reports from the Los Angeles Times and other outlets, however, there’s no evidence that the decision to end PREDICT was political. Though the White House has previously proposed decreasing funding for USAID and other global health programs, Carroll said that it’s unlikely anyone high up in the Trump administration even knew the program existed. (They might now. On April 1, PREDICT was granted a $2.6 million temporary funding extension, so the project and its partners can help identify the animal hosts of SARS-CoV-2.)

The scientists involved in PREDICT recently launched the Global Virome Project, which they hope will operate at a much larger scale. It aims to identify and assess all major viral threats within 10 years — at a cost of around $1.6 billion.

“It’s expensive,” said Mazet, the former director of PREDICT. “But it’s much less expensive than even 10 percent of big epidemics in the past, and it’s going to be minuscule compared to this one.”

For perspective, the U.S. government spent more than $2 billion trying to tamp down Ebola epidemics between 2014 and 2016 — and the CARES Act, passed last month to support an economy in freefall, costs around $2 trillion. In comparison, the cost of warding off viral outbreaks is “pennies on the dollar,” Epstein said.

PREDICT team members in Sierra Leone. Courtesy of Simon Townsley / PREDICT

It’s hard to say whether the project would have been able to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic. Although PREDICT identified 160 new coronaviruses in its decade of operations, none of them was SARS-CoV-2. Mazet said that PREDICT had partnered with a scientist at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, but the region just wasn’t a top priority for USAID, which was more focused on funding research into disease outbreaks in Southeast Asia. For her, this doesn’t suggest that the approach was wrong — just that any new effort needs to widen the area under surveillance.

Carroll thinks that the Global Virome Project and the foundation laid by PREDICT provide at least a place to start: a way to tackle the “viral dark matter” running through our planet, a potentially life-saving (and economy-saving) stopgap against future pandemics.

For now, those who have spent their careers warning of zoonotic diseases are sheltered in place like the rest of us. Many said that the pandemic should not be considered a “black swan event” — something random and unpredictable. The fact is, it was started by exactly the kind of spillover they had been warning about for decades. But that doesn’t make watching their fears play out any easier.

Before COVID-19, the team was struggling to get policymakers’ attention, fighting against competing funding priorities and short-term thinking. “We were raising the flag and waving it — to our own exhaustion,” Mazet said. “We hope the world is listening now.”