Schools are closed. Entire regions are on lockdown. President Trump has declared a national emergency and is weighing stimulus measures to help companies weather the storm.

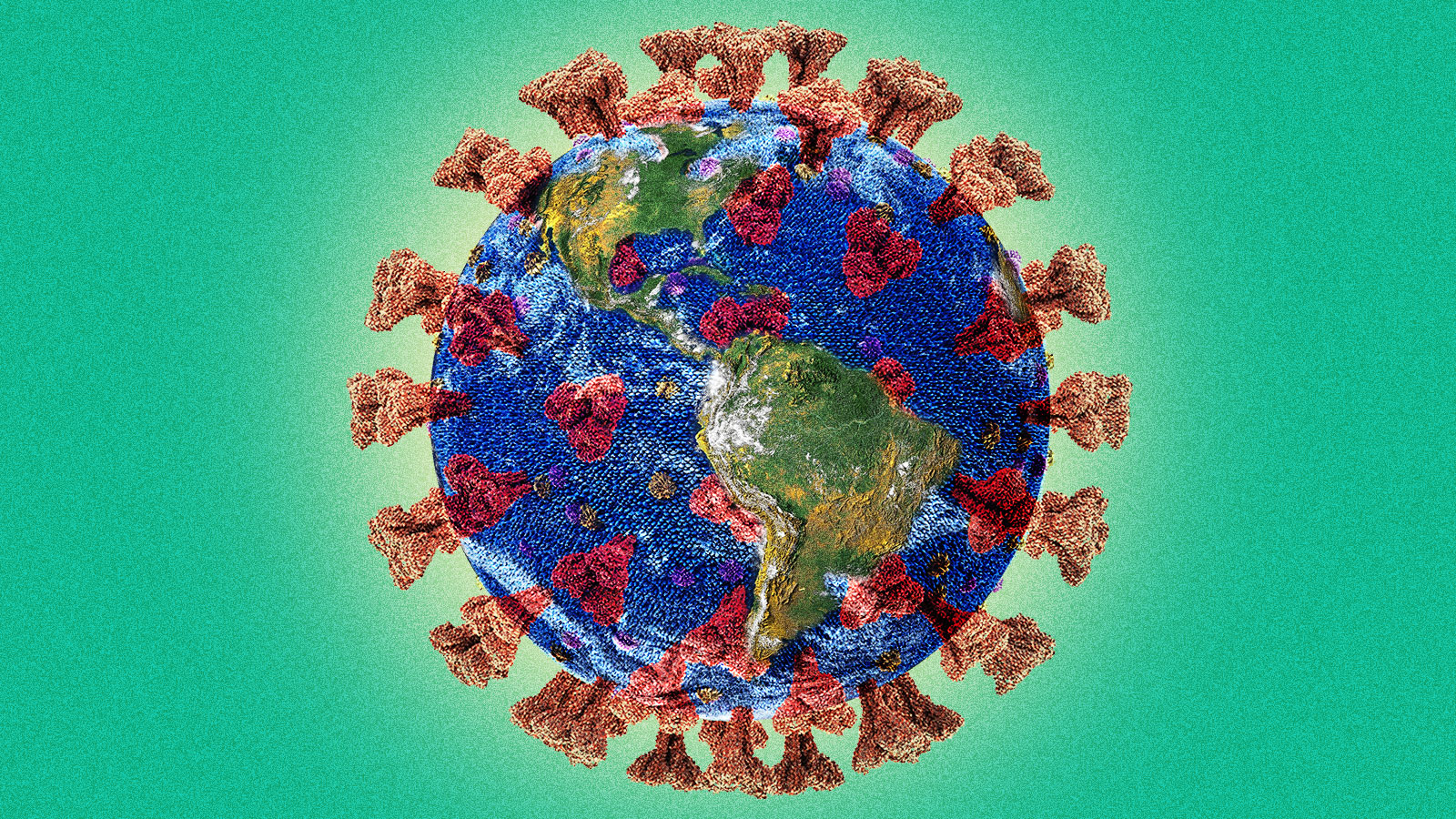

Countries around the world are beginning to react to the novel coronavirus with unprecedented speed in an attempt to curb its spread. There are already more than 135,000 cases worldwide and 5,000 deaths.

It’s a worldwide, planetary crisis. So why haven’t we seen this kind of sudden mobilization for human-caused climate change — another global catastrophe that has likely already claimed thousands of lives?

It’s common to bemoan a lack of action on curbing greenhouse gases, and wonder what the world would look like if governments treated the climate crisis like a pandemic, or even a war. But there are real reasons why climate change isn’t emblazoned on every newspaper headline and, like COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, discussed in sprawling emails at work and in seemingly every grocery store aisle.

“We are certainly under-reacting to climate change,” said Ed Maibach, a professor at George Mason University who studies climate change and public health, in an email. “Because it is a potentially catastrophic health threat that is likely to greatly harm human health and wellbeing for many generations to come.”

Part of the reason people recognize the threat posed by COVID-19 is its novelty. According to Maibach, people have a tendency to react strongly — or overreact — to risks that seem new, uncertain, uncontrollable, and life-threatening. COVID-19 displays all of these qualities.

Climate change, on the other hand, has long been seen as an approaching risk, one that will only affect people sometime in the future. A little less than half of Americans believe that climate change is harming U.S. residents “right now” (though that’s starting to change). Despite recent devastating wildfires in Australia and rapid ice melt at the poles, the framing of climate change as a long-term problem relegates it to back-of-mind for many. Sure, it’s a problem, the thinking goes, but one we can deal with later.

Familiar problems often get pushed to the side in favor of new ones, said Susan Clayton, a professor of psychology at Wooster College in Ohio. “Visually, if you stare at the same thing for a long time, you literally stop seeing it because your visual receptors adapt,” she said. That’s akin to how people respond to climate change. “We think, ‘Oh, climate change is bad. But I’ve been hearing about it for a long time. So I don’t necessarily need to pay attention to the stories coming out today.’”

It’s not just psychology preventing an all-hands-on-deck response. The climate crisis has been called a “super-wicked problem” — an issue that defies simple solutions or silver bullets. Wicked problems require large-scale, permanent changes to the way our societies run; they’re often exacerbated by other issues and sometimes require combatting powerful, entrenched interests. Poverty, for example, is a wicked problem: It has no simple fix.

As countries around the world take extreme measures to protect against COVID-19, there’s an assumption that such precautions will only be needed for months, maybe a year (get used to homeschooling, folks).

Climate change, on the other hand, requires decades of action — to 2050 and beyond. Though there would be an enormous benefit from an all-out mobilization in the short term, humans will be wrestling with a warming planet for at least the next century. There’s no vaccine for climate change, and, unlike the coronavirus, it won’t simply burn out over time.

There are still lessons to be learned from the current pandemic. “Many of the systems that we’re seeing are so crucial for addressing coronavirus are also greatly needed for addressing the health impacts of climate change,” said Mona Sarfaty, director of a program on climate change and health at George Mason University. Heat waves, extreme weather events, and rising air pollution from wildfires can put pressure on medical infrastructure; those support systems will need to be strengthened to prepare for a hotter climate.

Moreover, the sheer amount of action provoked by the COVID-19 outbreak shows what’s possible if governments and individuals could set aside short-term thinking. “There’s a sense that when people recognize that something is an emergency, pretty extreme measures can be taken,” Clayton said. Consider airplane flights, one of the most carbon-intensive actions an individual can take. “When it comes to something like this, people are not saying we can’t stop flying because it will hurt the economy. They’re just not flying.”