Photo: iLoveMountainsThe latest episode in the saga known as Big Coal’s Watergate began Tuesday when environmental and citizen groups filed a second notice of intent to sue the two largest mountaintop-removal mining companies in Kentucky. Appalachian Voices, Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, Kentucky Riverkeeper, and Waterkeeper Alliance notified ICG and Frasure Creek Mining of their intent to sue the companies for more than 4,000 violations of the Clean Water Act — these on top of more than 20,000 violations the groups already sued over back in October. As an editorial in the Lexington Herald-Leader wrote about the previous lawsuit against these same companies:

Photo: iLoveMountainsThe latest episode in the saga known as Big Coal’s Watergate began Tuesday when environmental and citizen groups filed a second notice of intent to sue the two largest mountaintop-removal mining companies in Kentucky. Appalachian Voices, Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, Kentucky Riverkeeper, and Waterkeeper Alliance notified ICG and Frasure Creek Mining of their intent to sue the companies for more than 4,000 violations of the Clean Water Act — these on top of more than 20,000 violations the groups already sued over back in October. As an editorial in the Lexington Herald-Leader wrote about the previous lawsuit against these same companies:

The environmental groups uncovered a massive failure by the industry to file accurate water discharge monitoring reports. They filed an intent to sue which triggered the investigation by the state’s Energy and Environment Cabinet. Also revealed was the cabinet’s failure to oversee a credible water monitoring program by the coal industry.

In some cases, state regulators allowed the companies to go for as long as three years without filing required quarterly water-monitoring reports. In other instances, the companies repeatedly filed the same highly detailed data, without even changing the dates. So complete was the lack of state oversight it’s impossible to say whether the mines were violating their water pollution permits or not.

This time around, none of the evidence that mines were violating pollution limits is in question. Moreover, the notice of intent to sue came at a particularly bad time for the coal industry and for Kentucky’s regulatory agencies, right when their momentum to hamstring the EPA’s authority was really starting to gather steam. Examples of recent anti-EPA efforts include:

- Passage of a bill by the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee designed to eviscerate EPA’s authority to enforce the Clean Water Act;

- Recent calls from at least three Republican presidential candidates to abolish the EPA altogether;

- A bill that was introduced in the Senate last February that really would abolish the EPA.

In the midst of Big Coal’s anti-regulatory crusade, however, Kentucky coal companies have given Americans another unmistakable reminder of exactly why it is that we really, really need an EPA — and why a poll for the Natural Resources Defense Council shows that the agency enjoys the overwhelming support of Americans [PDF] from across the political spectrum. The new evidence that was provided by environmental and community groups of fraudulent reporting of pollution discharges by companies — allegations that were written off by Kentucky regulators as “transcription errors” — is beyond embarrassing for a state that is complaining to Congress, judges, and anyone else who will listen about how the EPA is overstepping its authority to protect waterways. The premise of the most recent anti-EPA bill is that a bunch of jack-booted thugs from the EPA are coming in and mucking things up for the state agencies, who already have their regulatory houses well in order.

In testimony before the House committee that passed the bill last week, Len Peters, the secretary of the Kentucky Environment and Energy Cabinet (the agency that enforces environmental laws in Kentucky), told members of Congress:

Coal can be and is being mined in an environmentally responsible manner — we continue to make improvements, and the industry has been willing to do things better … We strongly believe the EPA’s objections to recent proposed draft permits for Clean Water Act 402 permits for surface mining operations in Kentucky were arbitrary.

Furthermore, it was Peters’ agency that refused to sanction one of these same companies for dumping waste into streams without even bothering to obtain a permit [PDF] and called allegations by environmental groups that the state did a poor job of investigating their complaints “bordering on specious.”

But the new analysis of reports submitted by coal companies over the last few years leaves the coal companies and state regulators with a lot of explaining to do.

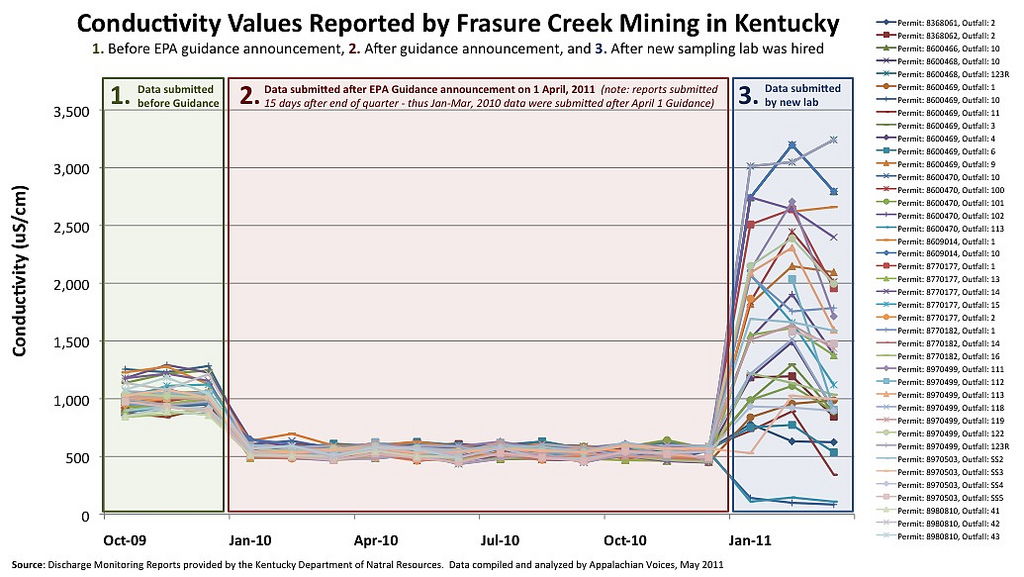

In a previous analysis, the water team at Appalachian Voices showed how monthly reports provided by coal companies of specific conductivity measurements in the discharge from mountaintop-removal mines were extremely suspicious (specific conductivity is a measure of salt in water and is an indicator of a host of pollutants such as toxic metals and other dissolved solids). In brief, reports submitted after the April 1 announcement by the EPA of a new guidance on conductivity levels in the discharge from coal mines (shaded red in the chart below) showed a remarkable drop from levels reported before the EPA announcement (shaded green). In fact, standard statistical tests showed that the chance that these trends could be explained by random transcription errors or natural variation was nearly one in a googol (that’s a 1 with a 100 zeros after it).

Appalachian VoicesAfter the previous lawsuit filed in October led the state to require companies to use new labs to monitor their mine discharge, the reports from these new labs (shown in blue), revealed even more stunning changes from the previous measurements. Moreover, conductivity was far from the only water quality measurement that showed jaw-dropping changes after the new water testing lab was hired — reported levels of manganese and total suspend solids showed similar trends. The previous reports were particularly hard to believe for anyone who has seen the water coming off of these mountaintop-removal sites (see vide

Appalachian VoicesAfter the previous lawsuit filed in October led the state to require companies to use new labs to monitor their mine discharge, the reports from these new labs (shown in blue), revealed even more stunning changes from the previous measurements. Moreover, conductivity was far from the only water quality measurement that showed jaw-dropping changes after the new water testing lab was hired — reported levels of manganese and total suspend solids showed similar trends. The previous reports were particularly hard to believe for anyone who has seen the water coming off of these mountaintop-removal sites (see vide

o from the Appalachian Water Watch team below).

Fortunately, this time the reported values pass the smell test, as they reflect the characteristics of independent measurements taken by scientists at universities and federal agencies. Unfortunately for the coal companies, these more realistic measurements reveal an enormous number of violations of all required monitoring parameters. Exceedances included everything from average monthly total suspended solids (TSS) levels up to 15 times higher than allowed by the permit, average monthly manganese and iron levels more than three times higher than allowed, as well as numerous pH, alkalinity, and acidity violations.

No laughing matter

By almost any standard, the actions of Kentucky politicians and agency officials since the EPA first began its more stringent reviews of mountaintop-removal permits have been absurd. For instance, the Lexington Herald-Leader reported this story on one Kentucky politician’s efforts to exempt the state from EPA enforcement:

“The EPA don’t understand mining,” House Natural Resources and Environment Chairman Jim Gooch, D-Providence, said at his committee’s hearing.

Gooch’s committee unanimously approved his House Bill 421, which would exempt coal mining from the federal Clean Water Act and other EPA regulation if the coal is used inside Kentucky and does not cross state lines. The lone critic at the hearing, environmental lawyer Tom FitzGerald, told lawmakers that about 20 percent of the sediment produced by coal mining goes into rivers that flow outside Kentucky’s borders.

David Gooch, president of Kentucky Coal Operators and Associates, provided his opinion of just who should be considered the real experts on water quality, which, of course, is not scientists at the EPA but politicians like himself:

“The EPA — these are not elected officials,” David Gooch said. “They are career bureaucrats who sit in their ivory tower in Washington, D.C., and decide what the science should be.”

Things got even wackier when another Kentucky politician introduced legislation to declare Kentucky a “sanctuary state” for coal mining after hearing about “sanctuary cities” declaring themselves exempt from federal immigration law.

These shenanigans from Kentucky politicians and regulators would be hilarious were the stakes not so high for the people who live in communities impacted by mountaintop-removal mines. But as more and more science comes out on the health impacts of living near mountaintop-removal mines, the picture for residents of Appalachian coal communities gets more and more bleak.

Just last week, researchers at Washington State University and West Virginia University published a peer-reviewed study entitled, “The Association between Mountaintop Mining and Birth Defects among Live Births in Central Appalachia, 1996-2003.” The study showed that six types of birth defects occurred more frequently in areas near mountaintop-removal mines, as compared to non-mining areas. The main types of birth defects included: circulatory/respiratory, central nervous system, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, urogenital and problems from “other” types of defects.

Melissa Ahern of Washington State University, one of the authors, explained:

[The study] shows that places where the environment — the earth, air and water — has undergone the greatest disturbance from mining are also the places where birth defect rates are the highest.

This study came on the heels of another study published last month in the American Journal of Public Health that concluded, “Residents of mountaintop mining counties reported significantly more days of poor physical, mental, and activity limitation and poorer self-rated health compared with the other county groupings.”

And just yesterday, a study was published in the journal Population Health Metrics that helps put these health impacts in perspective as they relate to the lawsuit filed Tuesday against ICG and Frasure Creek. An analysis of life expectancy data released with the study showed that:

- All of the eight counties in Kentucky where ICG and Frasure Creek operate mountaintop-removal mines are among the bottom 10 percent of U.S. counties in terms of life expectancy

- All but two have seen a decrease in life expectancy over the past 10 years

- Two of the counties, Perry and Pike, which happen to be the two biggest coal producing counties in Kentucky, were both among the bottom 10 (out of 3,147 counties) for trends in life expectancy between 1997 and 2007. While nationwide life expectancy increased by 1.5 years over the decade, average life expectancy in these two counties actually decreased by about a year.

- All eight of the counties have lost population over the 20 year period of the study

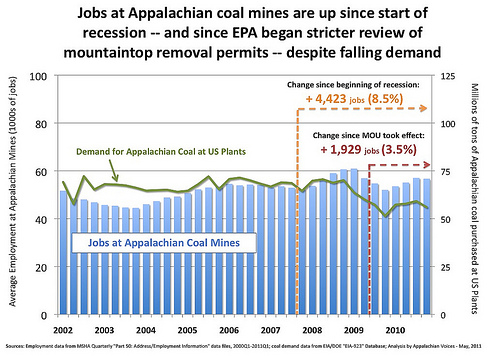

Finally, while coal companies and supporters in Congress argue that EPA regulations are destroying jobs, while mountaintop-removal mines create them, any objective analysis of actual data reveals that the opposite is true. Because underground mines employ more miners than mountaintop-removal mines for every ton they produce, it turns out that EPA’s stricter enforcement appears to be leading to an increase in mining jobs — far from the alleged “Assault on Appalachian Jobs” that the EPA is accused of by members of Congress. As shown in the chart below, the number of mining jobs in Appalachia has increased by 3.5 percent since the EPA first began its enhanced review of mountaintop-removal permits and that number is up by a whopping 8.5 percent since the start of the recession. By comparison, the overall U.S. economy shed 5 percent of its workforce over that same period.

Americans say: Let the EPA do its job!

The NRDC poll released earlier this year found that:

- Americans want the EPA to do more, not less. Almost two thirds of Americans (63 percent) say “the EPA needs to do more to hold polluters accountable and protect the air and water,” versus under a third (29 percent) who think the EPA already “does too much and places too many costly restrictions on businesses and individuals.”

- Americans do not want Congress to kill the EPA’s anti-pollution updates. More than three out of four Americans (77 percent) — including 61 percent of Republicans — say “Congress (should) let the EPA do its job.”

- The majority of Republicans — and all Americans — oppose the former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s plan to dismantle the EPA.

What Tuesday’s action by environmental and citizens groups shows is that the EPA needs to do a lot more to protect water quality of Appalachian streams and the health of Appalachian communities, not less. While some members of Congress and politicians in Kentucky and West Virginia will no doubt continue to make a fuss, the EPA would be neglecting its core responsibility if it backed off its recent enforcement actions one iota. The evidence tha

t the state of Kentucky is unwilling or unable to enforce the Clean Water Act is overwhelming and cannot be ignored.

Fortunately for the EPA, two thirds of Americans support them doing a better job of holding polluters accountable. The EPA should listen to Americans and to their own scientists, not coal companies or disgruntled politicians. And beyond the EPA’s enforcement of the Clean Water Act, it’s time for the Obama administration to strengthen its spine, stop playing politics, and put an end to mountaintop removal forever.

Click here to send a message to your member of Congress asking him or her to let EPA do its job and to oppose any efforts to roll back the agency’s authority.