After a yearlong delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic, world leaders finally began meeting in Glasgow, Scotland, yesterday for COP26, the most important climate conference in years. COP26 stands for the 26th session of the conference of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, a international treaty formed back in 1992 to curb global warming. Yes, our vaunted leaders have been doing this since the early 1990s. No, they haven’t yet significantly bent the curve. U.S. climate envoy John Kerry has called COP26 the world’s “last best hope for the world to get its act together.”

Below, you’ll find answers to everything you need to know about why COP26 matters and how to follow along over the next two weeks.

Who’s attending COP26?

The U.S.’ primary negotiator is Kerry, who has spent much of the last 10 months traveling the globe and trying to convince other countries’ leaders to increase their ambition to cut emissions ahead of the conference. President Joe Biden will make an appearance, along with at least 13 cabinet members and high-ranking officials. Republicans are also sending their own small delegation to make sure that “the international community has an opportunity to hear all perspectives from the United States,” Representative Garret Graves of Louisiana told E&E News.

Outside the U.S., 196 other countries are parties to the convention and will have delegates at the negotiating table. Notably absent from the conference will be the leaders of two countries that are among the biggest emitters in the world. Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia, will not be attending, and Chinese President Xi Jinping has said he most likely will not show up.

How long is COP26?

COP26 runs from Sunday, October 31 through Friday, November 12. While there’s sure to be an endless stream of news throughout that period, from speeches to protests to the unveiling of new global initiatives, the biggest announcements about the outcome of the negotiations are likely to come at the very end. Here’s the official COP26 schedule if you’re curious how it’s organized.

Can I stream it?

You can’t tune in to the actual negotiations, but key meetings and high-level events, like when Biden gives a speech, will be available to stream on the UNFCCC website. You can follow the UNFCCC on Twitter for updates. There’s also a packed program of affiliated events for the public being streamed live on the COP26 YouTube Channel. The full slate of programming, which includes panels, films, and poetry readings, is here.

What are the goals of COP26?

This year’s meeting has higher stakes than usual. When international negotiators finalized the Paris Agreement back in 2015, they determined that every five years, countries would be required to submit new plans for reducing their emissions, ratcheting up their ambitions over time. Since COVID-19 threw everything out of whack, the 2020 deadline was moved up to this year.

But how much each country promises to do to stabilize the climate isn’t the only item up for negotiation. Delegates will also be hashing it out over climate finance — the amount of money rich countries are giving to poorer ones to cut emissions and adapt to climate change. The past several conferences have also left leaders in a stalemate over developing the rules for an international carbon market, an unrealized provision of the Paris Agreement intended to help countries meet their targets more quickly and cheaply. (Scroll down for more on climate finance and the carbon market.)

How much more do countries need to do to prevent catastrophe?

In submitting their new climate plans ahead of the conference, parties to the Paris Agreement were supposed to increase their ambition. In April, Biden announced the U.S. would cut its emissions in half by 2030, which is roughly double what the U.S. has promised in the past. The E.U.’s new pledge is to cut emissions 55 percent by 2030, and the U.K. said it will slash emissions 78 percent by 2035.

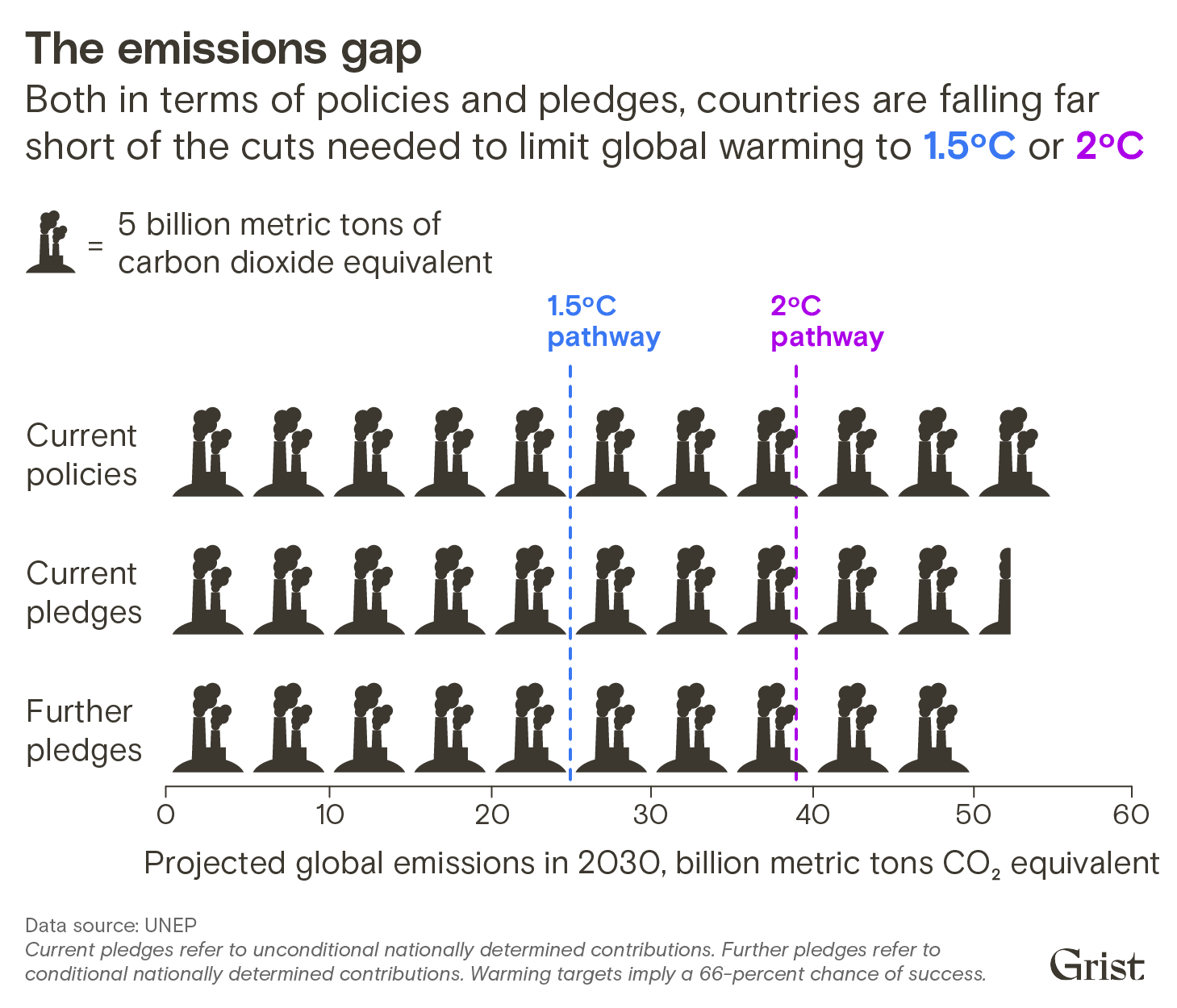

But while that all sounds positive, the latest pledges from around the world will only bring global emissions about 7.5 percent lower by 2030 than previous plans, according to the United Nations’ recent Emissions Gap Report. The report says further emissions cuts of at least 30 percent are needed to get on the lowest-cost track to prevent the most catastrophic version of climate change and comply with the Paris Agreement.

So what does this mean for the negotiations? One goal is to push countries to set stronger near-term targets, as cutting emissions over the next decade is essential, with some arguing for new plans to be submitted in 2023. Alok Sharma, a U.K. politician serving as the president of COP26, wants a deal to end the use of coal power worldwide, but it’s looking unlikely he’ll be able to get Australia or China on board. While China recently said it would end its financing of coal plants abroad, the country is still planning to build new coal plants within its borders.

Delegates will also seek an agreement to halt deforestation and strategize a global transition to zero-emission vehicles.

Why is climate finance so important?

Getting developing countries like India to agree to steeper emissions cuts may be impossible if the developed world does not commit more money to the cause.

At COP15 in 2009, rich nations agreed to provide funding to developing countries to help them adopt clean energy and adapt to climate change impacts like drought and flooding. They set a target of raising at least $100 billion in annual funds by 2020, and reaffirmed that goal six years ago when negotiating the Paris Agreement. One expert told Grist the $100 billion was the “glue that holds the Paris Agreement together,” since developing countries have done nothing to cause the climate crisis but suffer disproportionately from its impacts.

But while 2020 contributions are still being tallied, experts say the world likely missed the mark. In 2019, total funding amounted to $79 billion. In addition to the funding gap, the vast majority of the money has gone to climate mitigation projects, like renewable energy, when many countries desperately need more funding for adaptation. Since stepping into office, President Biden has vowed to increase the U.S.’ contribution twice — he pledged $5.7 billion annually in April, and then doubled it in September with a promise to send $11.4 billion a year by 2023 — but analysts say it still falls short of the country’s fair share.

Last month, a coalition of developing nations expressed frustration with calls that all countries pledge to reduce their emissions to net-zero, signaling that they would not increase their ambition without increased financial support.

What’s the deal with the global carbon market?

It’s been six years since the creation of the landmark Paris Agreement, but one key piece of it has yet to be worked out. It’s a section of the agreement called Article 6, which allows for the creation of an international carbon market. Countries can pay for emissions reduction projects beyond their borders, where they might be cheaper, and then count those reductions toward their own climate goals. For example, Germany could fund a renewable energy project in Bangladesh, or forest conservation in Brazil, and count the emissions benefits toward its own target.

This kind of emissions trading scheme is hugely controversial, with some experts saying it gives countries a flexible option that could speed up climate action, and others saying it could do the opposite. One of the risks is that the greenhouse gas reductions could end up being counted by both countries, which would ultimately dilute climate action. At every COP since 2015, negotiators have tried and failed to set up rules to ensure the market supports real progress. There is more optimism for COP26, as Brazil, which has stymied agreement on a carbon market in the past, has signaled an openness to compromise.