Amid sky-high energy prices, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and an ongoing global pandemic, the 27th United Nations climate change conference, or COP27, drew to a close with mixed results on Sunday.

The negotiations in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, ended with a historic agreement to set up a fund for “loss and damage,” a shorthand for the unavoidable effects of climate change that the developing world is disproportionately grappling with. But on a suite of other measures — such as phasing down the use of oil and gas and increasing funding for adaptation — COP27 delivered little progress, keeping the world on a path that will lead to warming of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), a critical threshold for avoiding catastrophic climate disruptions.

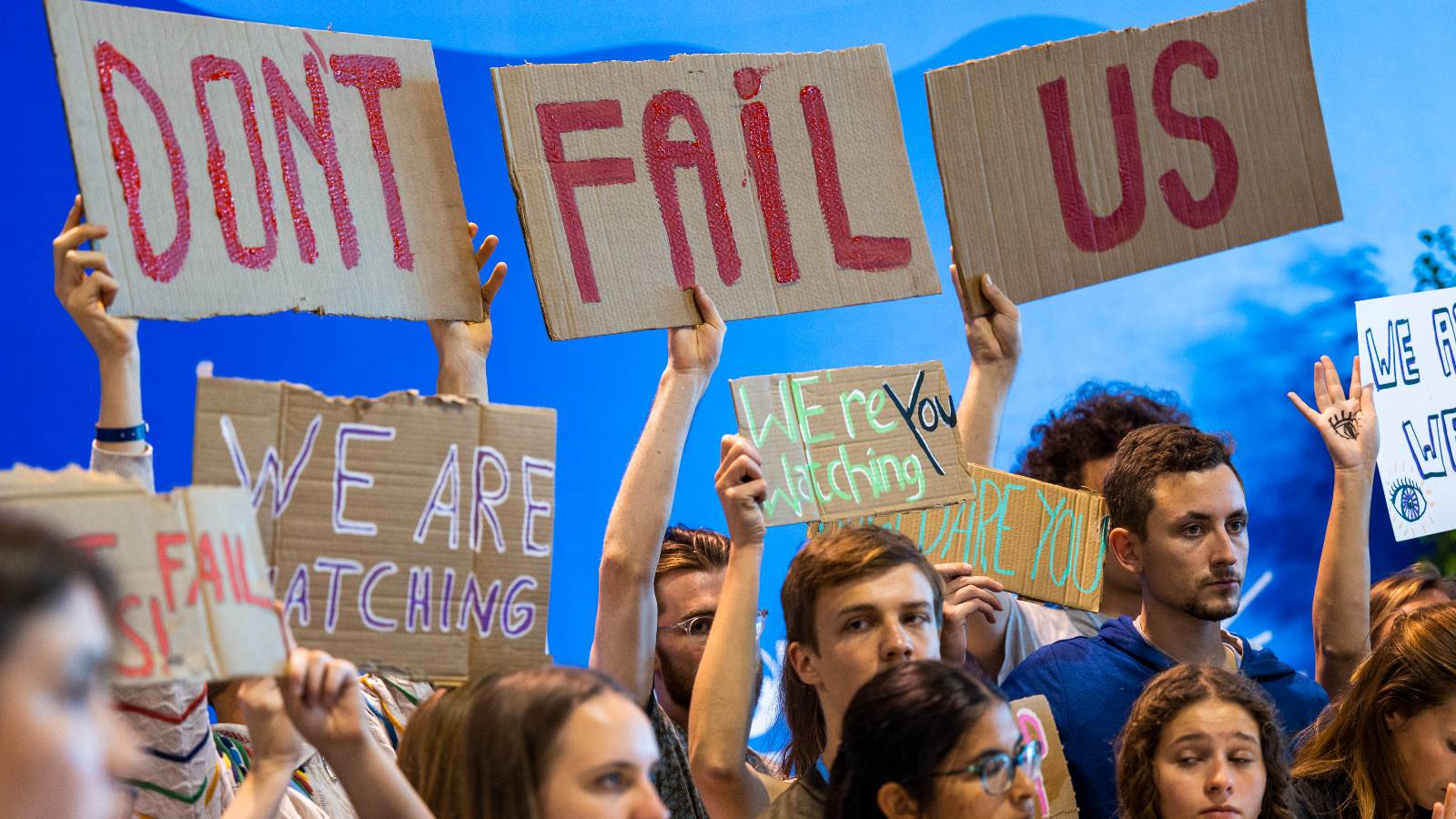

While many climate justice advocates praised the hard-won victory on loss and damage, celebrations were muted on Sunday.

“Without a phaseout of fossil fuels we are setting the world on a path for further losses and damages,” said May Boeve, executive director of the climate advocacy nonprofit 350.org, in a statement. “This is where the COP has failed.”

Negotiators overcame great odds to secure the landmark loss and damage deal. The conference was supposed to close on Friday but ran into early Sunday morning with bleary-eyed diplomats working through the night and into the early morning. Logistical challenges also pushed diplomats to the edge, with many blaming the COP27 presidency, headed by Egypt’s foreign minister Sameh Shoukry, for poor management. Food and water were limited at the venue, the Wi-Fi was spotty, and restrooms were at times out of toilet paper. At one point, a sewage line burst, flooding a street. And in the final hours of the conference, United States climate envoy John Kerry contracted COVID-19.

“But after the pain comes the progress,” said Molwyn Joseph, Antigua and Barbuda’s environment minister and the chair of an intergovernmental organization called the Alliance of Small Island States, reflecting on the late nights negotiators spent sparring to set up a loss and damage fund. “The agreements made at COP27 are a win for our entire world. We have shown those who have felt neglected that we hear you, we see you, and we are giving you the respect and care you deserve.”

Here’s a rundown of where the key issues from COP27 stand after the conference.

Phasing down fossil fuel use

Many countries arrived in Egypt eager to build on the progress made at last year’s conference in Glasgow, Scotland, which culminated in a landmark agreement to “phase down” the use of “unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.” While this was weaker than an earlier draft’s language to “phase out” all coal power and fossil fuel subsidies, it was the first mention of fossil fuels in a COP text.

But in the final hours of this year’s negotiations, those hopes were quashed by a coalition of mostly fossil fuel-producing countries led by China and Saudi Arabia. A proposal from India to agree to phase down all fossil fuels was thrown out. A push by the EU to reach peak greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 was also vetoed. Alok Sharma, a member of the British Parliament and president of COP26, lamented that it was a battle to even get countries to recommit to a key tenet of the Glasgow Climate Pact — a call on all parties to “revisit and strengthen” their plans to cut emissions. “I said in Glasgow that the pulse of 1.5 degrees was weak,” he said during the closing plenary session of COP27. “Unfortunately, it remains on life support.”

Climate advocates also criticized the final agreement for pushing for “low-emission and renewable energy.” While the reference to renewable energy was a welcome new development, the term “low-emission” could be used to justify the expansion of natural gas, which is technically lower emission than coal but is still a major contributor to climate change.

“We can’t afford any loopholes that leave room for the expansion of harmful fossil fuels and further destruction, like the dash for fossil gas on the [African] continent by European nations,” said Landry Ninteretse, regional director of the environmental group 350Africa.org, in a statement.

There were small marks of progress on climate mitigation over the last two weeks outside of the official negotiations. Fifty countries either unveiled national plans or regulations to cut their emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, or are in the process of creating such plans. Developed countries, including the U.S., also committed new funds to help Indonesia transition off of coal. And the keepers of the world’s three largest rainforests, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia, pledged to work together on forest preservation.

Loss and damage

The deal to set up funding for loss and damage is a major breakthrough in climate negotiations. Just two months ago, developing nations’ demand for a separate fund to address the toll of climate disasters appeared to be a far-fetched goal. Wealthy nations — led by the U.S., which is responsible for 20 percent of total historical emissions — opposed placing the issue on the official COP27 agenda, fearing that any agreement to fund loss and damage would open them up to unlimited liability. But escalating pressure from nonprofits, growing media attention, developing countries’ relentless and unified approach, and a last-minute reversal from the European Union brought the U.S. and other developed countries on board.

The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan calls for a new, direct fund for loss and damage, but many of the nitty-gritty details about the fund’s governance and structure will be decided by a transitional committee in the coming year. For now, the fund remains an empty bank account. Crucially, the committee will decide which countries will contribute to the fund and which ones will draw from it, major points of contention during negotiations. Developed countries want to expand the donor base to include wealthy developing countries and major polluters. China is a key target, and South Korea, Singapore, and some Gulf countries that have high standards of living are also on the list. The U.S. and other wealthy nations also want to restrict China from being able to receive money from the fund. For its part, China appears willing to contribute, but on a voluntary basis.

“Those details have to be worked out,” said Harjeet Singh, an advocate with Climate Action Network, an international coalition of more than 1,800 environmental groups. “A new journey begins to make sure it’s not an empty shell, and it helps the most vulnerable people access money. Now, it is all about making it happen.”

Adaptation funding

While countries may be lightyears away from reaching it, the 2015 Paris Agreement at least sets a target of limiting warming to 1.5 degree Celsius. This aim guides other mitigation goals, like the one most countries have adopted to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. But there is no specific global goal for adapting to a changing climate.

Adaptation projects in developing countries receive less than a third of all international climate funding committed by wealthy nations, and the gap between the cost of adaptation and the funding available continues to widen. Last year’s Glasgow pact “urged” rich countries to double their provision of international adaptation finance by 2025 and established a program to define and measure progress toward a global goal on adaptation. This year saw little movement toward that end.

Countries pledged an additional $230 million for adaptation this year, “but none of these announcements get really close to the $20 billion a year in additional finance that would be needed to meet the doubling goal by 2025,” said Joe Thwaites, an expert on international climate funding at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The COP27 pact only mentions the doubling goal in a request that the U.N. climate convention finance committee produce a report on doubling adaptation finance by COP28 next year, with little detail on what the report would contain. Countries agreed to come up with a framework to track adaptation progress but continue to disagree on what measuring, reporting, and review will look like. Because of COPs’ history of producing pledges that are never met, developing countries, like those in the Africa bloc, want more formal reassurance that new finance goals will be achieved.

Carbon markets

Last year at COP26, countries established rules for a new global carbon market that would for the first time permit carbon trading under the 2015 Paris Agreement. Carbon markets allow for countries and companies to buy credits in forest conservation or solar farms in other countries, for example, and count the emissions reductions towards their own targets.

These markets have been heavily criticized for not actually preventing or removing greenhouse gas emissions and for allowing ongoing pollution by wealthy nations. This year, countries were supposed to work out the details to avoid these types of outcomes, but they didn’t get very far.

Countries and advocates wary of the potential for greenwashing through carbon credits hoped to establish a centralized way to oversee trades, review their validity, and create transparency. The final text allows governments to keep information about trades confidential.

“This transparency loophole risks being exploited by countries seeking to shroud their emission trades in secrecy,” said Jonathan Crook, a global carbon market expert with Carbon Market Watch, in a press statement.

Another unresolved question from last year was the issue of double counting — a scenario in which both the buyer and seller of carbon credits put the emissions reduction on their books. Double counting is banned under the carbon market established in Glasgow, but it still occurs on the voluntary market when companies buy carbon credits from countries. The COP27 agreement creates a new, second-tier market where companies can buy credits as “mitigation contributions,” implying — but not requiring — that if they’re counted by the country where the project is located, they shouldn’t also be claimed by the corporate funder.

Another outstanding debate from COP26, the question of what can be considered carbon “removal” on the new market, has been pushed to next year. Vague, early recommendations from a technical supervisory body, which would have included controversial methods like carbon capture and storage, failed to establish human rights protections, and were released after no consultation with nonprofits or advocates, were sent back for revision.