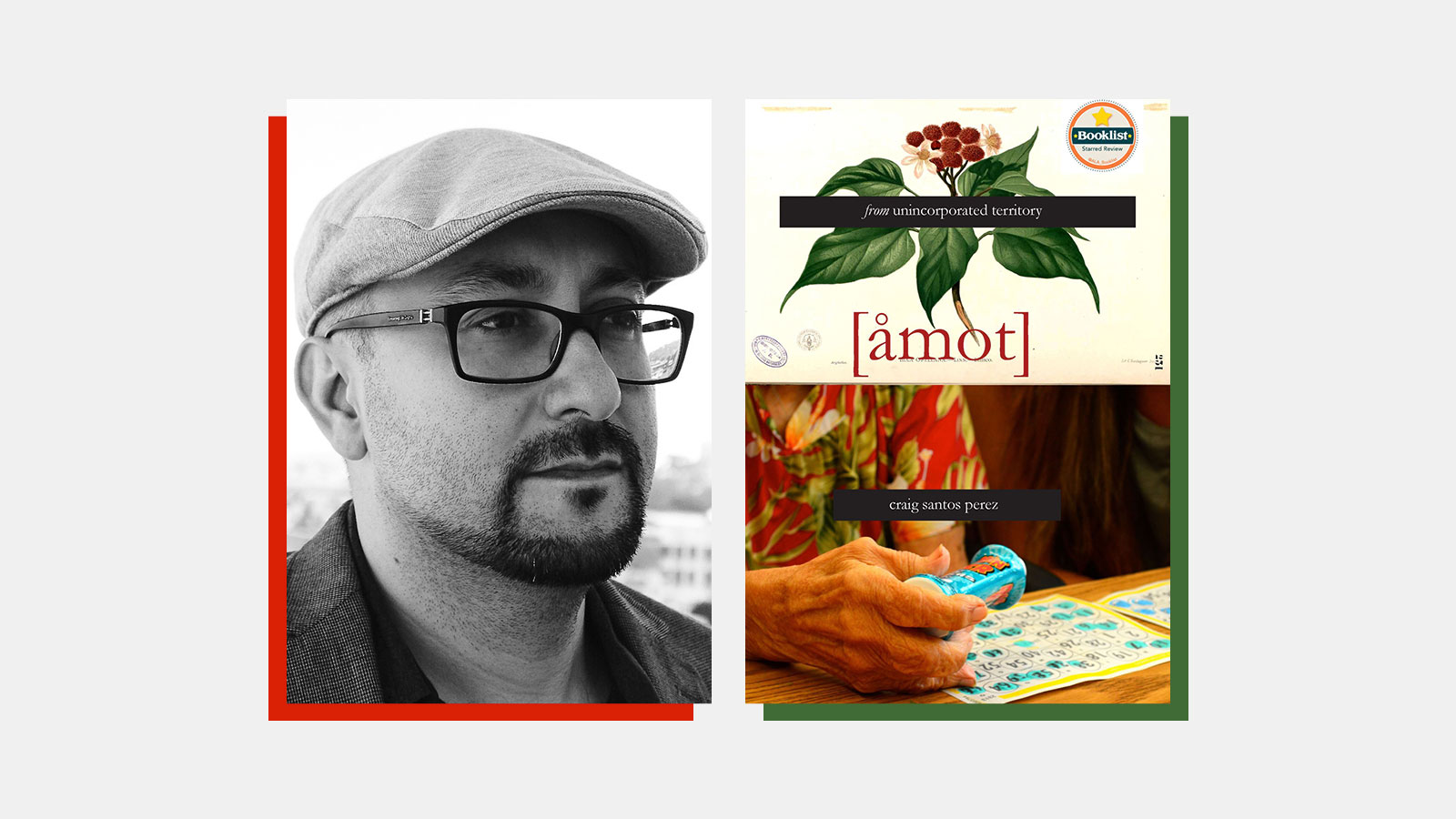

There’s a scene in Craig Santos Perez’s book of poems from an unincorporated territory [åmot] that feels eerily familiar. The author, an English professor at the University of Hawaiʻi, is walking through the San Diego Zoo when he sees a caged Guam sihek, an endangered native kingfisher bird of Guam.

Perez was born and raised on Guam, but this is the first time that he’s seeing the bird in real life, with its blue tail, green wings, and orange and white feathers. The creatures no longer live in Guam’s jungles, decimated by invasive brown tree snakes brought by U.S. military ships. Like many other CHamorus from Guam, Perez grew up accustomed to the silence of native birdsong.

Like Perez, I’m indigenous to the Marianas, and even though I grew up on a neighboring island, I spent a lot of time on Guam as a kid. Back then, snake-induced power outages felt normal, and so did the birds’ absence. It wasn’t until I was in college, walking through the Bronx Zoo, when I too saw the sihek, imprisoned for its own survival thousands of miles away from home. It felt jarring.

Even stranger is the feeling of seeing my language and experiences reflected in a book, especially one that’s highly acclaimed. Last month, Perez became the first Pacific Islander to win a National Book Award, standing in a suit at the New York City awards ceremony in front of a crowd that included Oprah. The next day, 8,000 miles away on Guam, WhatsApp threads lit up with the YouTube clip of his acceptance speech in which he thanked the crowd in CHamoru.

That distance is part of what made that award feel so momentous. In his poetry, Perez grapples with the invisibility of Guam (“Are you a citizen?”), the ongoing legacy of colonialism, the consequences of continuing militarization, and the ever-ascending threat of rising seas. “The rape of Oceania began with Guam,” he quotes at one point.

There’s a heavy grief in his exploration of what CHamorus have lost, and stand to lose with climate change, and a more personal grief embedded in his poetry about his grandparents, who passed away during the writing of the book. But there’s also a lightness to his work, especially in his lists of modern-day åmot, or medicine, for stateside CHamorus feeling mahålang for home.

I spoke with Perez last week to hear his reflections on the book and how his poetry relates to climate change, environmental justice, and the broader experiences of Indigenous peoples. This interview has been condensed and edited.

Q. You’ve mentioned that you’re writing for yourself and your family and our people, but you’re also writing for the broader global community in the U.S. and beyond. One of the challenges that Indigenous people face is the way our stories are often erased from history, or in the case of Indigenous Pacific peoples, we are literally relegated to the margins of maps or footnotes in textbooks. What do you see as your book’s role within that broader context?

A. So much of my work is about making the struggles of our people visible, and the history and politics of Guam, in particular, visible, on a national and international stage. That’s a way for me to write against the erasure of Pacific Islander histories specifically and Indigenous histories in general. I’ve been so inspired by Native American writers for decades writing against their own erasure and raising their voices to highlight issues facing their own communities, and so I wanted to do the same thing with my own work. And as you know, the connection to the environment, to lands and waters is a core component of Indigenous identity and culture, and so I wanted to always have that at the forefront.

When our homelands and our peoples are invisibilized it makes it easier for colonial nations or corporations to exploit us and to turn our homelands into sacrifice zones. But when we expose these issues, that creates a way for us to not only cultivate empathy for our struggles, but also to establish alliances and solidarity with other communities who have experienced similar kinds of environmental justice issues. And then I think it also empowers our own people to continue to keep fighting and struggling for justice. And so for me, poetry and storytelling play a pivotal role in the environmental justice movement.

Q. Your poem about the Guam sihek resonated with me because I had the same experience at the Bronx Zoo: encountering the bird in a cage thousands of miles away from home, that I had never seen or heard in the wild, and feeling struck by the irony and sadness of it. Can you share more about that experience and what you were hoping to convey with your writing?

A. Growing up on Guam when I did was the time when the birds were all disappearing, and zookeepers came in and “saved” the last remaining wild birds. I don’t have any memory of the native birds in Guam at all besides just studying them in school and looking at pictures in the classroom. And so when I did see that bird for the first time at the San Diego Zoo, it was similarly kind of an uncanny experience. I’m still kind of processing the depths of what I felt in that moment. Part of it was just feeling the deep loss of extinction, endangerment, extirpation, and so on, but at the same time feeling this deep sense of survival and resilience.

I wanted to also honor the birds in the same way I would honor my grandparents in the poems. I was thinking about extinction, not just a species loss, but also as a whole matrix of loss: the cascade that happens in the jungles, the rainforest, what happens when birds are disappeared from the landscape? What happens to the people who are close to these birds when they’re gone? The birds have deep meaning in our culture and still have meaning today. But obviously, these are different things when they’re no longer wild.

Q. One of your poems describes how “mapmakers named our part of the ocean ‘Micronesia’ because they viewed our islands and cultures as small and insignificant.” Then you list the empires that have taken over our islands, and their effects, a sort of progression of colonization, and at the very end you describe our islands slipping under rising seas. What were you thinking about when you started this poem about colonization and ended it with climate change?

A. Colonialism has led to the environmental destruction of our home islands: Our islands are often used for very extractive industries, whether it’s plantation agriculture in Hawaiʻi or on Guam, the military using our lands and waters for bases and military testing, and so on. All of these industries are fossil fuel-based, and they’ve all led directly to the rising sea levels and all the other climate change impacts that we see in the Pacific and globally. Things that we need to do to change this, they’re almost impossible to implement because, whether our islands are still colonized or in terms of the independent Pacific, they all exist within these neocolonial capitalist frameworks. And so in order to address climate change, we need to also reckon with the legacy and ongoing impacts of colonialism. And so for me, it’s always been important to be part of the decolonization movement alongside environmental justice and climate justice, because it’s all connected.

Q. Another poem you wrote that resonated with me was about how diasporic CHamorus become foreign in their own homelands after leaving, as their islands change and grow strange to them. I was wondering if you could talk about what an acceleration of outmigration due to worsening storms and other climate change impacts could mean for our people and our culture.

A. In the beginning of the highlighting of the Pacific in climate change discourse, there was a lot of rhetoric about, “If Pacific Islanders are forced to move from our homelands, we’re nothing, we’re nothing without our islands,” which was a rhetorically powerful rallying cry. But my critique of that is, that’s true, but at the same time, we have to look at our diasporic Pacific communities. Even when we leave our homelands, we’re not nothing. We don’t just become dead souls, but we still carry our culture with us, even if we’ve been forced to migrate. Obviously it’s tragic, when and if we have to migrate because of climate change and we have to do everything to, of course, prevent that, so that we can stay in our homelands. But at the same time, if that future does come, I think we know it’s important for us to highlight the strength of our diaspora communities and to have faith in our people that we will be able to maintain our cultures and languages even if we’re forced to leave home.

Q. Speaking of language, I noticed that throughout your book you deliberately included many CHamoru words and phrases. For Native peoples, the speaking of our languages is often in and of itself a political act because of how they’ve been suppressed. What went into your decision and what did you hope to accomplish?

A. Through poetry, I found the space where I could kind of reclaim the language even if it’s just single words or simple phrases or even quotes from the rosary in CHamoru, for example. For me, poetry, like a lot of Native poetry, became a space of language reclamation in the face of the long history of language colonialism and erasure.

I actually read a study that found that there’s a relationship between biodiversity loss and language loss. And part of the thesis was that because, letʻs say, a rainforest in the Amazon is being cut for timber or something and a lot of those tribes are being displaced, forced to move to the city, and in the city they have to speak Spanish or some other colonial language.

There are a lot of narratives of doom and extinction like that. But I think there are a lot of Indigenous people, despite displacement and colonialism, they’re still able to be resilient and maintain culture and language within diasporic spaces. Not ideal, but I think it speaks to the power of Indigenous peoples.

Q. Throughout your book, you write a lot about your grandmother: playing bingo with her, watching her rub achiote seeds to make red rice, listening to her speak CHamoru. Can you tell me more about her? When you think about the brutal Japanese occupation that her generation experienced during World War II and subsequent loss of land to the U.S. military, how do you see it relating to the challenges that our children’s generation will face?

A. She was 19, I think, at the beginning of the occupation. And during the march to Mañenggon, she was actually pregnant with what would have been her first child. But unfortunately, during the march, she had a miscarriage. I will always be struck by her resilience to wrap her fetus in banana leaves and carry her daughter the rest of the way on that march and go on and keep living life. She was a very soft-spoken woman and very devout, of course.

I canʻt even fathom what that generation went through during that time. Not only did they experience the war and the occupation and all of that sudden violence, but then also just the slow violence after that of the military taking over so much land, displacing so many families from their ranches and from their sources of sustenance, forcing them to speak English in school and just the whole violence of colonial education and acculturation. Just imagining the changes she saw in our island from the 1920s all the way up to just a few years ago across her 96 years of life. Even though we’re facing another slow violence with climate change, I do think at least my generation can learn from that generation how to endure, how to survive, but also how to be resilient and to keep fighting for what we believe in. My grandma wasnʻt some kind of radical activist or decolonial activist or anything like that. But she definitely loved our culture and instilled a love for everything CHamoru in us. We have different struggles to fight, but the similarity is to continually fight for what we love, and to do everything we can to protect our families and to give our kids the best life possible while still trying to maintain our cultures.