This story is part of the Grist series Coming to our Senses, a weeklong exploration of how climate change is reshaping the way we see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the world around us.

When I, a born-and-bred Pennsylvanian, first moved to Seattle, I found that people in the Pacific Northwest like to talk about the summers by way of explaining why they live there. “Wait until July,” they told me, smirking, as I shivered beneath a spitting late-May sky the exact same color as the sidewalk. Here is what happens in July: The clouds over coastal Washington dissipate, a brilliant sun bursts onto the scene with the carefree abandon of the girl at the Bat Mitzvah who just got her braces off, and the landscape becomes a kaleidoscope of sparkling topaz and emerald.

It is lovely. It is also not true summer, at least not for anyone who grew up east of the Mississippi.

Summer is walking outside of your house and instantly glistening. It is a dew point at 70 degrees, grass hot and lush, air so thick with humidity it almost quenches thirst. It is the sworn enemy of sleeves, bangs, and leather upholstery. In summer, one is constantly reminded, for better or for worse, that one inhabits a human body.

The longer I was deprived of that sticky experience, the more I craved it. Eventually, after seven summers in Seattle, deprived of true heat and humidity, I started to wonder if humans — like animals — require the conditions of their native habitats to thrive. Perhaps I needed, on a biological level, to return to western Pennsylvania. This was not the only reason I moved home, but it was something I relished when I stepped out of the airport in the middle of August, my skin instantly damp from the moisture steaming off the asphalt.

But within a week, I was in hell. Moments of domestic bliss spent tending my new garden turned to small nightmares when I looked down from my clippers to find a smattering of gray mosquitoes feasting on my calves. A night spent drinking under a pink sunset in a friend’s backyard would be followed up not with a hangover but with colonies of welts up and down my thighs and shoulders. (Remember that hot and humid weather is not conducive to wearing a lot of clothes.)

I would lie awake scratching my wounds until my sheets were speckled with my own blood, fantasizing about becoming a mad scientist type who devotes her life to destroying every mosquito on Earth. I began to carry at least one bottle of insect repellent everywhere I went, dousing myself so thoroughly that I left a cloud of DEET and citronella in my wake.

Even after years on the relatively bug-free Puget Sound, I had not forgotten that my body is superlatively adored by mosquitoes. But even so, I found this level of summer exsanguination shocking. I do not remember it being this bad, I repeated to myself, worrying that so much time away from home had made me remember Pittsburgh’s sweltering months in too flattering a light.

It turns out, both mosquitoes and I cherish the same thing when it comes to climate: mugginess. Mosquitoes need tepid, still water in which to lay eggs and develop, and such conditions go hand-in-hand with warm, wet air. Spring flooding is already a troublesome reality across Appalachia, where heavy rains and steep mountainsides conspire to overflow the creeks and rivers that run through narrow lowlands. The standing water that results from those overflows is prime spawning ground for mosquitoes, especially as the spring months get balmier.

“A bunch of things will influence mosquito populations, including human development patterns,” says Kaitlyn Trudeau, a data analyst with the nonprofit research organization Climate Central. “But the two things that are thought to be most influential are temperature and precipitation. And we know that climate change will make things get hotter, we know that it will contribute to heavy downpours and warmer winters. These conditions are prime examples of things that will increase mosquito populations.”

In 2020, Climate Central published an analysis projecting which regions of the United States would see the greatest increase in “mosquito days.” These are defined as days when the temperature falls between 50 and 95 degrees Fahrenheit and humidity is above 42 percent. The list included the Ohio Valley, a stretch of Appalachia that follows the Ohio River from its origin in Pittsburgh to its meeting point with the Mississippi River at the western tip of Kentucky.

A 2017 Army Corps of Engineers report on projected climate conditions warned that Pittsburgh’s annual mean temperature is predicted to increase from 50 degrees F at the turn of the century to 59 degrees by 2100. The average annual streamflow, the amount of water running through Appalachia’s many tributaries, could increase by 15 percent by 2040.

In other words, I had voluntarily moved back to prime mosquito country.

A mosquito’s worst offense, it must be said, is not violating a person’s enjoyment of a summer evening. It is most notorious as a vector of disease: malaria, dengue fever, Zika, West Nile virus. 2018 was Pennsylvania’s wettest year in history, with one and a half times the normal amount of precipitation inundating the state. Matt Helwig, a biologist with Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s West Nile program, recounts that 120 Pennsylvanians contracted West Nile that year. About three-quarters of those patients developed neuroencephalitis, a serious swelling of the brain caused by the virus.

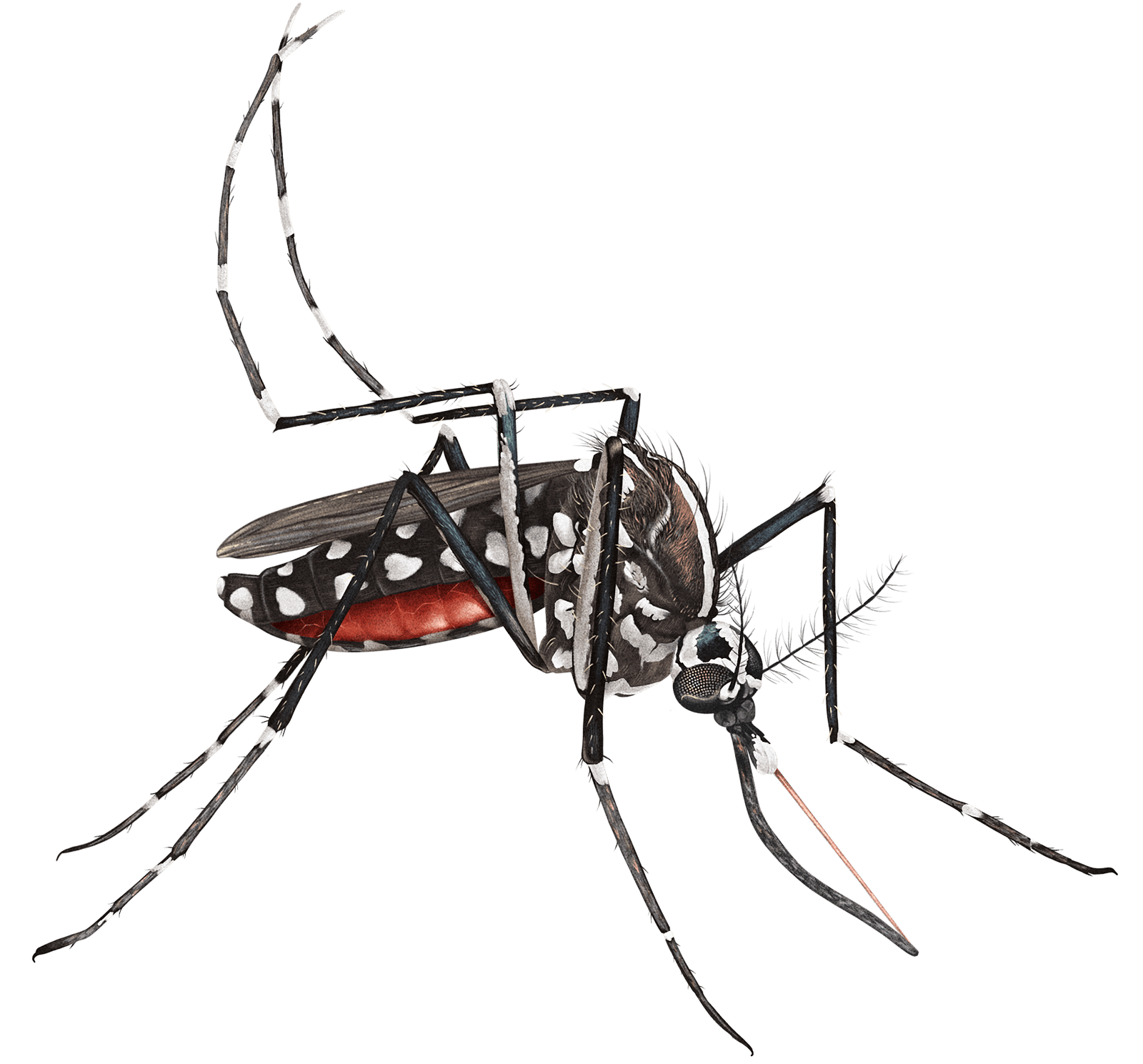

The increase in average temperatures is also shifting different species of mosquitoes northward, which has implications for both welt-ridden skin and the spread of disease. The Aedes albopictus, or Asian tiger mosquito, is a relative newcomer to Pennsylvania, having first been identified in the state in the late 1990s. It’s a particularly dangerous vector because it bites as much as nine times more than other mosquitoes. To make matters worse, mosquitoes actually bite more in hotter weather — they’re at their most voracious around 93 degrees, according to one study.

“The reason mosquitoes are biting you is to take a blood meal so they can lay eggs, and most will feed on you until their gut is full with blood and then they’ll fly away,” explains Helwig. “But the Asian tiger has to feed on multiple people or bite multiple times on the same person to get the same blood meal.”

“Blood meal” is a horrific enough concept to have to contemplate while melting into a towel poolside. But it’s more challenging to consider my own role — or at least, that of my species — in bringing the A. albopictus into my home.

A. albopictus has several common names including the Asian tiger mosquito and the (less racially charged) forest mosquito. The latter comes from the fact it is a woodland-dwelling insect that has traditionally made its home in organic shelters like “tree holes, bamboo stumps, coconut husks,” according to one primer from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But like most other species of mosquito, it has adapted to inhabit less enchanting features of the human-made environment: old tires, wheelbarrows, neglected trash cans.

A. albopictus is native to East Asia, but as the planet’s most invasive species of mosquito, it can now be found all over the world. Its first American colony was identified in Houston in 1985. The species is believed to have made its way across the globe via the international used tire trade. An old tire is a perfect vessel in which a mosquito colony can travel — a sort of RV for arthropods. The larvae can stow away in the tire’s grooves and wells as the colony makes its ways overseas, and then when the tire arrives at its resting place — usually in a pile outdoors at an auto shop or waste facility — the first rain transforms it into a thriving mosquito habitat.

My fellow humans did this. The mosquitoes have merely adapted to the new world we created. They have made a home of our refuse, finding opportunity in the most fetid and neglected corners of our domain. (We might call them true capitalists if they sought money instead of human blood.)

I cannot say this realization has helped me make peace with the mosquito. I still panic when I feel a tinny buzz in my ear, still eagerly attempt to squash every flitting gray speck I see. But there is something to be said about any exercise that pushes us to better understand the very flawed world we made, all while doing what we can to improve that world.

A. albopictus is part of my habitat, and I can protect myself from it as best I can, but I do not have to begrudge its existence here in the Ohio Valley. Who wouldn’t want to live here, after all — where you can feel summer right on your skin, all its sumptuousness and stupor and silky moisture. To me, for now, it is worth the itch.