On an overcast spring day in Washington, D.C., Georgetown University professor Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò paced the length of a triptych blackboard, telling his students a story: In the 18th century, European men published iconoclastic arguments declaring that all individuals were born free and equal.

“These are not merely abstract philosophical questions,” Táíwò lectured. “People are fighting wars over, among other things, different answers to these questions.”

Remarkably, many of these wars were won by those on the side of “free and equal,” Táíwò pointed out. Think of the American and French revolutions: Their ideas about inalienable rights and consent of the governed quickly transformed from heresy to common sense. This common sense, however, failed to provide the promised rights and freedom to most of the world. Women in the U.S. only won the right to vote more than a century after the American Revolution, and around 750 million people lived under some version of colonial rule by the middle of the 20th century. Even as they gained independence, redrawing the borders of the modern world, disparities endured. Black South Africans, for instance, didn’t secure voting rights until 1994.

“Just for reference,” Táíwò said, pausing for emphasis, a large beaded necklace with an Africa-shaped pendant hanging over his gray T-shirt, “I’m older than that. That happened in my lifetime.”

This tension between what philosophy says about the world and the ways the world actually works is what animates Táíwò’s teaching and writing. A 32-year-old assistant professor, he’s already one of the country’s most publicly prominent philosophers, and he’s certainly the most vocal philosopher working on issues related to climate change. Less than five years ago, he was toiling in relative obscurity on his PhD at UCLA; today he publishes regularly not only in professional philosophical journals, but also in publications like The New Yorker, The Guardian, Foreign Policy, and too many others to list. His first two books, Reconsidering Reparations and Elite Capture, have both been published within the last six months. He tweets to his 48,000 followers daily.

When I first called Táíwò on the phone in February, I told him that, if I had to gloss Reconsidering Reparations, I would call it “a theory of everything for the social justice left.” I didn’t mean this to sound flip. If anything I meant it as a compliment about the book’s deftness in connecting issues as seemingly disparate as disability rights, fossil fuel divestment, basic income proposals, and police reform.

“Just for the record,” he responded, laughing, “that doesn’t sound flip at all.”

That Reconsidering Reparations became a “theory of everything” with climate change at its center is something of an accident. When he sat down to write his first book, Táíwò was interested in staking a position in a far narrower debate: Under what conditions could a program of reparations for those disadvantaged by the legacy of colonialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade actually achieve justice?

Táíwò’s notion of justice is broad. While many philosophers have traditionally conceived of justice as concerned above all with the resources available to people, Táíwò thinks the concept must be expanded to consider their “capabilities” — what kind of lives they are empowered to lead, not just the money and goods they have. If you want to achieve justice in a sense this expansive, he argues, redistributing cash and other material resources will only get you so far.

Over and over again, the question of how to realize this justice led Táíwò to climate change. Given its disproportionate effects on populations for whom the legacies of colonialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade loom the largest — think the tens of millions of Bangladeshis who stand to be displaced by sea-level rise, or the unique vulnerability of the entire African continent to temperature rise and decreased rainfall — each additional degree of global warming seemed to undermine the good that any reparations project could do.

“Are any of these other measures that we take toward racial justice going to have staying power in a world that’s 3 degrees hotter?” he has said. “In a world where there is rampant instability in our energy and housing systems? In a world of mass human displacement? In a world where the elites of the world feel very threatened?”

Though Táíwò is loath to declare loyalty to a particular ideology, he readily identifies as a leftist, and his views on climate change perhaps sit most comfortably under the umbrella of eco-socialism. Still, he is willing to follow his philosophical arguments to positions that are controversial in some leftist quarters. He has argued, for example, that carbon removal is an essential tactic in the pursuit of environmental justice, and he has opposed calls for bans on solar geo-engineering research, calling such arguments “performatively colonial.” What he opposes most of all is moralizing: If political purity gets in the way of improving the actual life experience of people now and in the future, then it has no place in his account of justice.

“He’s not a doctrinaire anything, in the end. You really see this in his interest in climate politics. He’s like, ‘Let’s just do whatever works when it comes to this really urgent problem,’” said Daniela Dover, a philosophy professor at the University of Oxford who taught Táíwò when he was a graduate student. “I don’t feel like I can predict what he’s going to say.”

While Táíwò’s ultimate vision is of a world where economic and political power is massively redistributed, it’s clear that he thinks rapid decarbonization is the world’s most immediate priority. Every degree of warming puts his conception of a just world further out of reach.

“It’s very difficult to not treat climate change as one of the central questions confronting philosophers and people in general,” he told me.

What sets Táíwò’s work apart is that he thinks the English-speaking world’s traditional accounts of justice are increasingly useless — and that the challenges posed by climate change can demonstrate why.

Anglo-American political philosophy still operates in the shadow of John Rawls, whose 1971 doorstop A Theory of Justice single-handedly revived an academic field that many considered dead. Rawls argued that justice consists of whatever principles all of a society’s members would agree to if they were to assume what he called a “veil of ignorance” — in other words, if they did not know the exact circumstances under which they would live.

The idea is that a state could pursue justice by basing its laws and rules on principles that people would endorse if they knew nothing in advance of facts like their race or income. If every country operated on these grounds, then we would live in a just world. Whether or not you’ve heard of Rawls, if you have an idea that justice is more or less synonymous with something like fairness — and that the laws of states and governments should be set up in a way that advances this fairness — your thinking bears the mark of his influence.

Táíwò thinks this approach might make sense if we all lived in completely autonomous countries with representative and functional governments. But we don’t. Given this, Táíwò argues that we cannot pursue justice without recognizing that we live in an interconnected world that distributes risks and benefits in profoundly unequal ways, regardless of what any of the 193 members of the United Nations might want. This is largely, Táíwò argues, because we are still living out the consequences of the Industrial Revolution and European colonialism, which established global patterns of wealth and resource accumulation that push some countries toward failure and others toward success, decades after many colonized countries gained independence.

Indeed, the very fact that we live in a world composed of nation-states — and the shape and institutions of those states themselves — is the product of these worldwide historical developments. Africa’s present-day borders, for instance, are largely the work of colonial administrators. (In 1885, European leaders staged a now-infamous conference in Berlin to hammer out the details; no Africans were invited.)

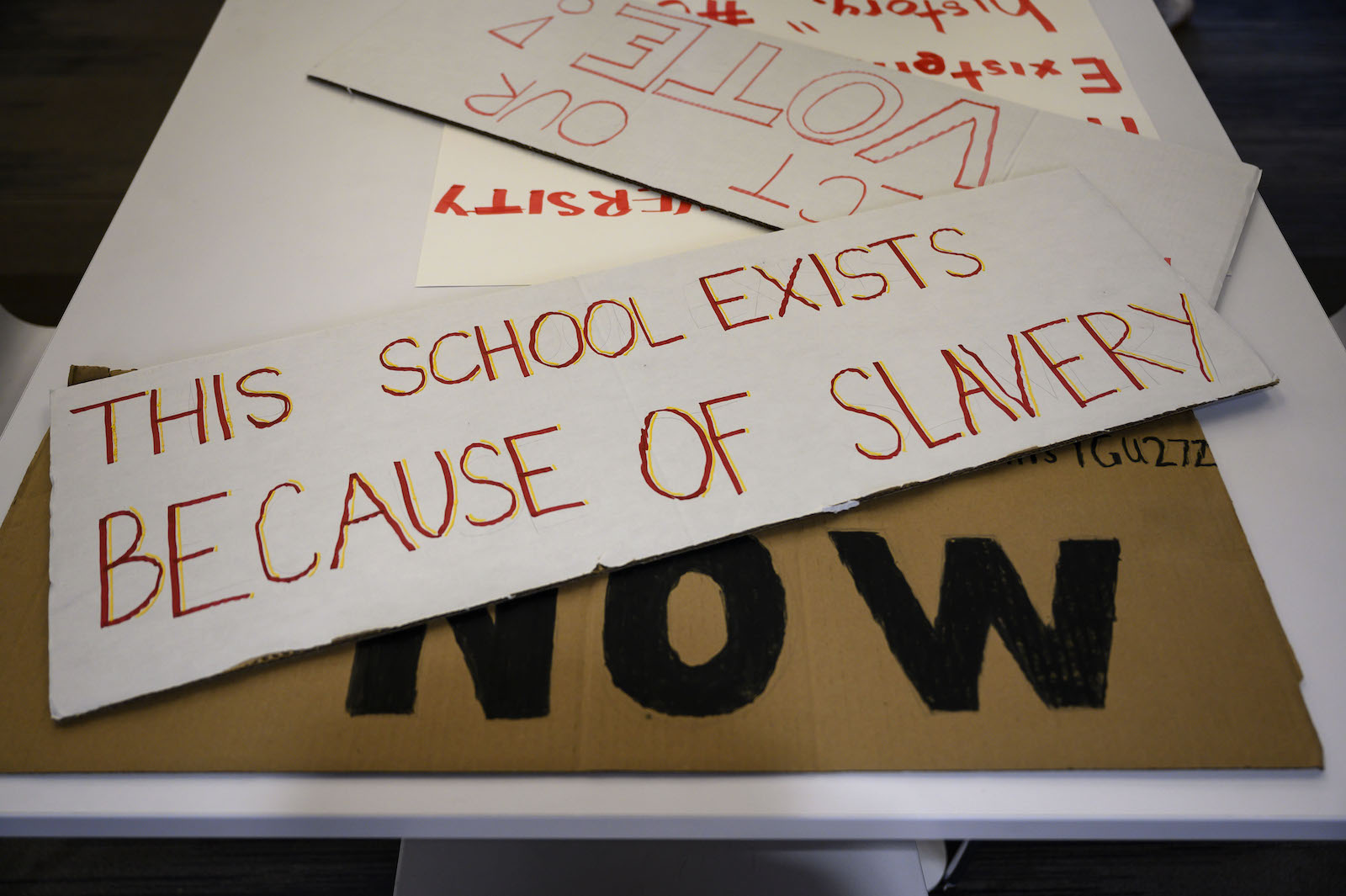

When looking at contemporary disparities, like the two-decade gap in life expectancy between an American and a Nigerian, Táíwò sees the winds of this history at work, delivering unearned benefits to some and unwarranted burdens to others. Sometimes, those currents scramble our moral expectations, our tidy accounts of heroes and villains. One chapter in Reconsidering Reparations notes that some early Georgetown students’ parents leased the labor of enslaved Africans to the university to cover their tuition, and that Georgetown itself sold hundreds of enslaved people to balance its books. Right after that, however, Táíwò observes that the benefits Georgetown accumulated in part through the slave trade now flow directly to him, a Black man, paying his salary and lending him the institutional prestige that helped him secure the contract to write this very book.

This paradox is at the core of Táíwò’s argument about the perils of a certain kind of identity politics, an argument he makes in a recent essay that became his latest book, Elite Capture, published in May: Identifying a single person who can accurately and fully represent the voices of a marginalized group is easier said than done.

“Treating group elites’ interests as necessarily or even presumptively aligned with full group interests involves a political naiveté we cannot afford,” he writes. In the worst cases, this well-meaning presumption can enable the “elite capture” of justice-oriented projects. That might look like the Black mayor of Washington, D.C., having “Black Lives Matter” painted onto city roads while sidestepping the demands of protests on those same streets. For Táíwò, the emerging norm in social justice organizations and universities of automatic deference to people like him risks uplifting an already-privileged few in place of actually improving the lives of the oppressed.

“Perhaps,” he writes, “after we in the chattering class get the clout we deserve and secure the bag, its contents will eventually trickle down to the workers who clean up after our conferences, to slums of the Global South’s megacities, to its countryside. But probably not.”

The story of Táíwò’s own ascent to the chattering class underscores not only the moral perils he sees in a certain brand of identity politics, but also the ways that history tees up life outcomes in ways that only become visible in retrospect — another major theme of his work.

President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 brought a sea change in U.S. immigration policy, making “skilled labor” the primary determinant of an individual’s ability to immigrate, rather than ethnicity and national origin. Large-scale immigration from countries in Asia and Africa became possible, and Táíwò’s parents left Nigeria in the early 1980s to pursue graduate school in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Táíwò was born. His childhood memories start in the suburban Midwest. His mother’s career as a pharmacologist took the family from the affluent suburbs of Cincinnati to the affluent suburbs of Indianapolis and then to nearby Muncie — “Parks and Rec Indiana,” as Táíwò calls it. As a kid, he was absorbed by Ender’s Game, the mythology of the Star Wars expanded universe, and Super Smash Brothers Melee.

The legacy of anti-colonial independence movements loomed large in the memories of Táíwò’s parents — they taught their children the pan-African anthem — but so too did the 1967 Nigerian Civil War, which saw the country fracture along ethnic and religious lines as the predominantly Igbo populations in the southern Biafra region seceded following ethnic cleansing in the Muslim-dominated north. Táíwò recalls that many of the other Nigerian-Americans he knew in the Midwest “had genocide in living memory.” As they struggled to convince him to practice the piano, Táíwò’s parents reminded him how lucky they were to own one: In Nigeria, they’d had to leave their piano behind after the war broke out.

This backdrop shaped how Táíwò experienced political events in the U.S. In April 2001, when Táíwò was 11 years old, an unarmed 19-year-old Black man named Timothy Thomas was shot by police officers in a Cincinnati neighborhood a few miles from Táíwò’s home. The community uprising that followed bore a striking resemblance to those that would follow Michael Brown’s death in Missouri in 2014, and George Floyd’s in Minnesota in 2020. It shook Táíwò’s inchoate sense that American life could be insulated from the kind of violence his parents had left behind in Nigeria. In neighborhoods not far from their quiet Ohio suburb, it often wasn’t.

An experience later that year, however, underscored the vast privilege that accompanied the family’s American citizenship. After finding out that hijackers had steered planes into the World Trade Center, Táíwò began stashing Pop-Tarts and other imperishables in his bedroom. His parents, mystified, asked him what he was doing. He explained that this is what he’d picked up from them about what war meant: needing to prepare for deprivation and insecurity. They laughed — such precautions were not necessary in a country like the U.S. They wouldn’t be leaving their piano behind.

“Part of the point of their immigrating here,” he reflected in an interview as an adult, “was to become the sort of people that war didn’t happen to.”

These experiences informed a principle at the core of Táíwò’s philosophical viewpoint: that justice is a question of how both resources and personal security are distributed between different countries and communities as well as within them.

A “directionless and unmotivated” student, in his own words, Táíwò aced standardized tests but got unremarkable grades — he didn’t like being told what to do, and even less being told what to think — dashing the Ivy League hopes of his parents. Still, he was able to get into Indiana University on a scholarship. He started out studying economics and political science, thinking those were the disciplines that could answer his nascent questions about why society was organized the way it was. He quickly became disillusioned, and that disillusionment crystallized one day while he was studying macroeconomics. The textbook offered as an example a man in Bangladesh who worked as a taxi driver, tailor, and an array of other odd jobs.

“The book was like: Why is this person poor?” Táíwò said to me. “I expected an answer that would have to do with anything about Bangladesh. And the answer was like: ‘This guy doesn’t understand the principles of specialization and trade.’”

“Their assumptions seemed to background stuff that I thought should be foregrounded,” he remembered of those courses. “I just figured philosophy was the place you went to think about background assumptions.”

With his first philosophy courses, Táíwò was hooked. Applying to graduate school to continue studying philosophy after he earned his bachelor’s degree in 2012 was a natural choice, given the ambient pressure he still felt from his parents to pursue higher education. But he had little investment in making a career as an academic. His stint as a saxophonist in his high school band led to him dabbling in a handful of other instruments, including guitar, and he was more interested in becoming a musician. (He’s described his musical sensibility as “somewhere between The Roots and Miles Davis.”) UCLA didn’t seem like a bad place to make that happen. He took a year off before grad school to try his hand at it.

“Failing to become a musician was a very good thing for me,” he admitted.

At UCLA, Táíwò studied under philosophers who encouraged him to pursue the broad, big-picture questions that animated him — questions about how contemporary society is structured, and how it could be restructured in a just way — rather than reorienting himself toward the arcana associated with academic philosophy. The wide scope of Táíwò’s inquiry led him to take much of his coursework outside his home department, in classes on history and cultural studies. Táíwò’s dissertation advisor, the philosopher AJ Julius, described their time together as the “uncommon experience of watching someone in permanent revolution.”

“He came into it knowing he was always going to be an outsider to the institutions of professional philosophy, but determined to use those institutions for his own purposes,” said Dover, who sat on Táíwò’s dissertation committee. “I didn’t feel I had anything to teach him at all.”

Though this approach may make Táíwò an outsider to contemporary philosophy, with its emphasis on ever-narrower definitional questions, it also makes him more like the classic conception of a philosopher — Táíwò’s ambition is no less than Aristotle’s when the latter sat down to spell out exactly how to live the good life. In asking questions about things as fundamental as the nature of justice, Táíwò found himself arguing with some of the philosophical tradition’s towering figures — an argument that plays out, among other places, in the pages of his first book, Reconsidering Reparations, where he takes on John Rawls.

Táíwò thinks Rawls’ famous theory of justice is wrong on multiple counts. The first is its focus on states. Táíwò argues that many governments are incapable of securing just or fair outcomes for their citizens, because many of the biggest disadvantages they experience are imposed externally: Think here of the tiny Pacific island nations that stand to disappear altogether due to sea-level rise caused largely by emissions from early-industrializing countries like the United Kingdom. History has set some states up to succeed, and others to fail.

Second, Táíwò argues that Rawls proposed a “snapshot view” of justice: It establishes what a just set of outcomes would be at a single point in time, failing to recognize that circumstances today were often created in the past — and that what looks like justice to people alive today may harm their grandchildren. Building out coal power, for example, might make sense to present-day residents of a country like India — it’s cheap electricity that can power air-conditioning on increasingly scorching summer days — but such decisions contribute to global warming that will bring suffering to future generations.

“The nature of the system is that it moves resources from yesterday to today to tomorrow,” Táíwò writes.

To answer skeptics of his account of the guiding role that historical forces play in the present, Táíwò asks simply that we take a look at the best available data about the world around us (which is helpfully laid out in Appendix B of Reconsidering Reparations): The vast majority of former colonial powers, like the U.K. and France, have average incomes well over twice that of many of their former colonies. Metrics on life expectancy, maternal mortality, dietary adequacy, literacy, sanitation access, civil liberties, and political rights follow similar patterns. Taken together, these disparities make formerly colonized countries most vulnerable to the ravages of climate change — an ironic outcome, given that their late industrialization makes them least responsible for climate change in the first place.

Environmental injustice and climate change, in other words, dole out damage in profoundly unequal ways. This is visible not just between countries, but also within them; the theft of land from Indigenous peoples in North America, for instance, has made their descendents more vulnerable to extreme heat and drought. Much of this sounds familiar, or at least intuitive, to those immersed in the rhetoric of the environmental justice movement. It’s all connected. But Táíwò provides a grand unified theory that explains why it’s all connected, and points to ways of remaking the world in accordance with philosophical principles of justice.

To some, a philosophy that accounts for the combined injustices of all of modern history might appear to put an ideal world out of actual reach. But although Táíwò is most thorough in his account of the way the world actually is, he doesn’t lose sight of the ideal. Instead, he ratchets his ambitions for the ideal higher. Because the colonial world order remains a force in people’s lives, a reparations project that achieves justice cannot simply compensate for past and present damages — it must be what Táíwò calls a “worldmaking project,” concerning itself not just with wealth and resource distribution but with building and maintaining environments that allow everybody to flourish within them. In this sense, he considers his project a “constructive” approach to reparations.

Táíwò thinks that this is best pursued by prioritizing the self-determination of individual communities, their ability to chart the course of their own destinies. On the local scale, he’s spoken approvingly of citizen assemblies in contrast to the mass electoral politics we normally associate with democracy. (Recent experiments in this form have contributed to securing abortion rights in Ireland and wind power in Texas.) On the global scale, he calls for reviving egalitarian visions of an alternate international system, such as the New International Economic Order that Ghana, Nigeria, and dozens of other decolonized countries demanded of the United Nations in the 1970s.

These ideals may seem far off, but much of Táíwò’s time and energy is spent arguing for concrete, intermediate steps toward these goals. He recently teamed up with three other academics to publish a proposal outlining the possibility of a publicly owned, democratically controlled carbon removal authority in the U.S., which could be modeled after municipal water or trash systems, or regional electric cooperatives. In April, he co-authored a report documenting the ways that the U.S. and other rich countries could immediately restructure or cancel debt owed by poor countries as a first step in a program of climate reparations.

“Climate reparations should not be thought of simply as compensation for past environmental, economic, and social damages, but as world making,” the report reads. “Debt justice and enhanced climate finance should help build a platform for countries in the Global South to achieve low-carbon development and robust, resilient infrastructure.”

On a cursory read, the sweeping history of what Táíwò calls “global racial empire” could lead you to think there’s no room in his account for human agency, for bucking the course of history and changing the world right now. But Táíwò doesn’t think history dictates what people do. History may create the constraints and boundaries within which people make choices, but they still make choices. The more those boundaries are expanded, the more actions that are available to people, Táíwò’s argument goes. And, perhaps, if people are more free and empowered, they will be more likely to coordinate and solve big problems like climate change.

In our conversations I got the sense that, if there’s one thing about Táíwò’s account that keeps him awake at night, it’s how close this belief is to an article of faith, rather than a reasoned philosophy. He knows there’s no guarantee that greater human freedom and empowerment will stop climate change, or bring about justice. If given more choices, people might pick the wrong ones. Nevertheless, Táíwò thinks it only makes sense to let them try.

“He’s hoping to find a common-sense radicalism,” Julius told me. “I think he’s trying to help radical thought and common sense to recognize themselves in each other.”

The day I visited Táíwò in Washington, the city’s famous cherry blossoms were in early bloom. The gray sky delivered ominous bursts of wind, warnings of the tornado that would touch down just across the Potomac River later that evening. Nevertheless, we successfully avoided rain as we walked past Georgetown’s tony townhouses to Martin’s Tavern, a watering hole for the city’s well-heeled. Táíwò patiently and thoughtfully fielded my questions as fragments of chatter about registering kids for prep school floated by from other tables. Sensing my anxiety about leaving the right amount for a tip, he quietly threw a few extra bills on top of the check as we walked out. Knowing the correct amount mattered less than giving someone a little more money right now. It might not have been ideal, but it got us part of the way there.