It’s hard to think of something more wholesome than gardening. But the New Zealand gardening collective at the heart of Birnam Wood, a new political thriller by the Booker Prize-winning author Eleanor Catton, have a rebellious streak. The guerrilla gardeners trespass on unused land to grow carrots, cabbages, strawberries, and other crops. They tap private spigots and snipe the occasional tool from a shed in a wealthy neighborhood, imagining themselves as environmental revolutionaries.

Bookshelves are beginning to teem with radical environmentalists. In the sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, a group called the Children of Kali target conspicuous “carbon burners,” knocking jets out of the sky and sinking yachts. A purported ecoterrorist also drives the plot of the mystery Hummingbird Salamander by Jeff VanderMeer, sending the main character on a risky mission into the world of wildlife trafficking. Then there’s Stephen Markley’s novel The Deluge, released in January, where a group of climate radicals called 6Degrees tries to avoid detection by the surveillance state as they instigate attacks on oil and gas infrastructure.

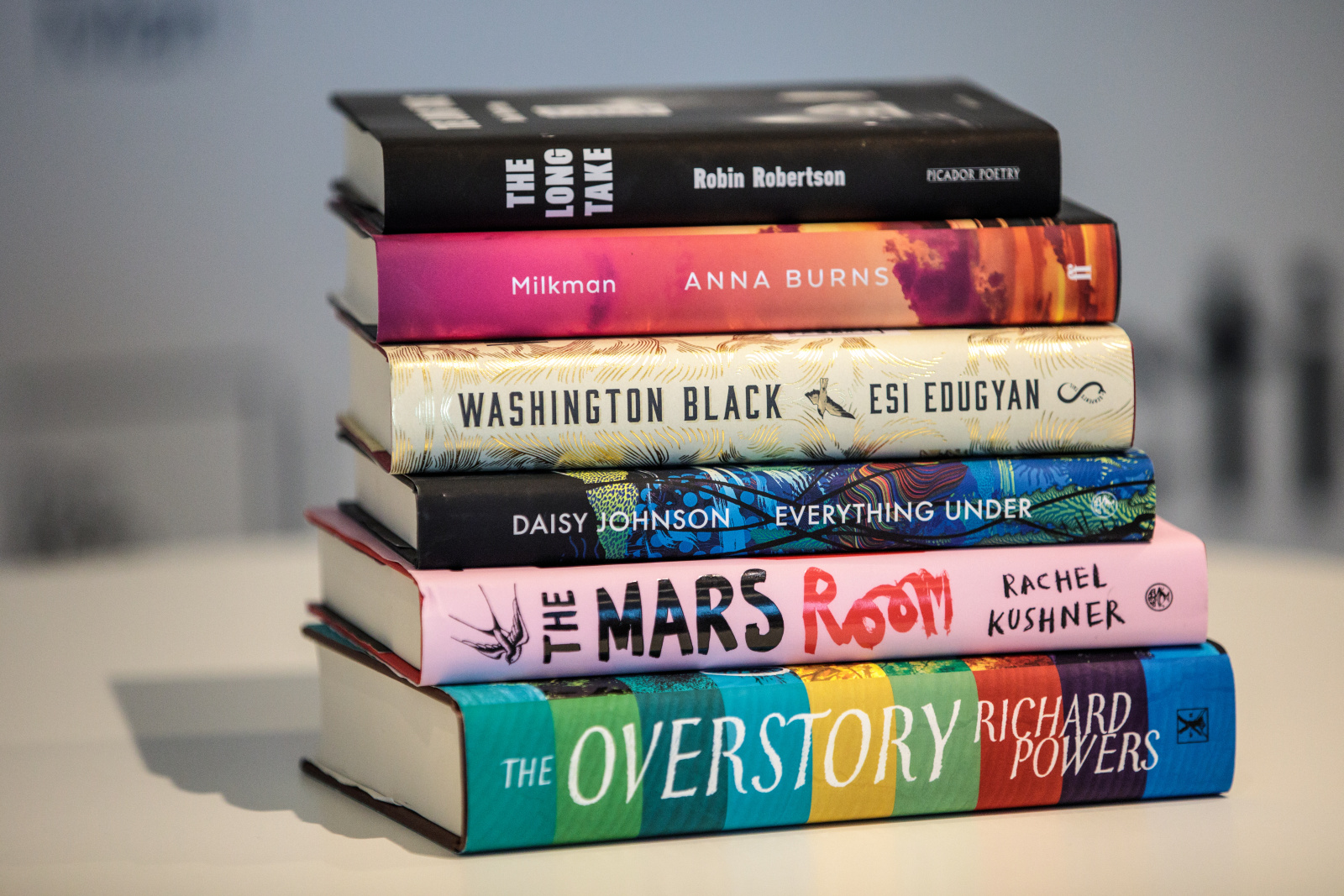

That eco-sabotage has captured so many authors’ imaginations seems to reflect a broader frustration with governments’ failure to rein in carbon emissions — a feeling that decades of peaceful protest weren’t enough, and the world is out of options. It has propelled climate fiction, once a niche genre, into the mainstream. Think of The Overstory by Richard Powers, a sweeping novel that follows activists who seek to save trees at all costs, employing human barricades, tree-sitting, and arson. It won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize and generated glowing praise from Bill Gates as well as Barack Obama, who said it “changed how I thought about the Earth and our place in it.”

History suggests that fictional stories about eco-sabotage, sometimes called “monkeywrenching” after Edward Abbey’s book of the same name, could inspire people to try something similar in the real world.

“The world right now is ripe for radical activism,” said Dana Fisher, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland. Last week, a report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the risks from climate change — both present and future — were even more severe than previously thought. In the last year alone, heavy rainfall submerged a third of Pakistan with massive floods and China endured a heat wave more intense and longer-lasting than any in recent history. The panel of scientists called for a “substantial reduction” in the use of fossil fuels, with the United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres declaring that the world needed a “quantum leap in climate action.”

Yet earlier this month, the Biden administration approved the Willow project, a ConocoPhillips oil drilling operation that could release up to 260 million metric tons of carbon over its lifetime. For progressive groups in the United States who spent recent years working with the Biden administration to pass the landmark Inflation Reduction Act, the single largest climate package in the country’s history, it felt like a betrayal — one that might lead to a shift in tactics.

“I mean, everybody knows that we are nowhere near where we need to be,” Fisher said. “And so the natural progression is you’re going to see folks, particularly young people, rise up.”

Apocalyptic storylines have long dominated environmental fiction — including Nevil Shute’s On the Beach, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road — a frame that’s tailor-made to ramp up concern about planetary crises. “I think that a lot of climate fiction has been perhaps stuck in this mold of cautionary tales, of bad climate futures,” said Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, an English professor at Colby College in Maine.

Now reality is doing the work that fiction once did. With a quorum of Americans sufficiently frightened about the world’s trajectory — a full quarter of the population is now “alarmed” about climate change — writers are branching out. Authors are modeling for readers a transition from “apathetic awareness” to “meaningful action” by showing different kinds of political engagement, Schneider-Mayerson said.

That might explain the variety of unconventional activism in recent novels, such as the guerrilla gardeners of Birnam Wood and the utopian commune in Allegra Hyde’s Eleutheria (2022). Hyde’s novel follows a woman who joins a camp of eco-warriors in the Bahamas, after she read a guide to fighting climate change called Living the Solution. “I felt like a lot of climate fiction that I was encountering was purely apocalyptic,” Hyde told Grist. “But I wrote this because I wanted to use fiction as a space to imagine other possibilities, imagine utopian possibilities, and maybe open up that imaginative space for people.”

Eleutheria was inspired in part by The Great Derangement, a nonfiction book by the Indian author Amitav Ghosh published in 2016 that bemoaned the lack of serious literature about climate change, especially outside of science fiction, at the time. “I think it is a real call to arms to fiction writers to recognize how storytelling can and does shape how we live our lives in the real world,” Hyde said.

Another inflection point for climate fiction was the widespread popularity of The Overstory, the 512-page novel that brought attention to the ways trees communicate and wound up as a global bestseller. “It wasn’t hived off into the usual silos of climate change or speculative fiction, but was treated as a mainstream novel,” Ghosh told the Guardian in 2020, noting that he’s seen an “outpouring of work in this area” since the book’s publication.

Monkeywrenching is also spilling over into film. The movie How to Blow Up a Pipeline, coming out next month, is inspired by the Swedish writer Andreas Malm’s book of the same name, a manifesto that encourages sabotage and critiques the pacifism of the climate movement. The film adaption takes that idea and turns it into a work of fiction, following a group of disillusioned young people on a heist to sabotage an oil pipeline. The trailer shows them making bombs and features dramatic background music punctuated by klaxons. “They will defame us and claim this was violence or vandalism,” one activist says. “But this was justified.”

Previous films have tended to “pathologize” activists who destroy property, psychoanalyzing them to figure out what was wrong with them, Schneider-Mayerson said. “I think maybe there’s a sense that, like, you can kind of touch these topics, but you can never endorse it.” On the other hand, How to Blow Up a Pipeline ends with “a wink and a nudge,” according to an early review of the film. “You can almost hear the movie say that the sabotage doesn’t need to stop when the credits roll,” Edward Ongweso Jr wrote in Vice.

The idea that people might take a cue from the movie isn’t far-fetched, experts say. “I can just say for sure that there are a whole bunch of dissatisfied young people around the country,” said Fisher, the sociologist. “And if they start watching movies about blowing up pipelines, what will that do?”

Fiction has inspired radical activism before. In 1975, the novelist Edward Abbey published The Monkey Wrench Gang (the origin of the term “monkeywrenching”). The book’s eco-warriors destroy property in an effort to save the wilderness of the Southwest, pouring sand in the gas tanks of bulldozers and plotting to destroy dams. Abbey divined that his book might generate some copycats. “This book, though fictional in form, is based strictly on historical fact,” he wrote in its epigraph. “Everything in it is real or actually happened. And it all began just one year from today.”

It took a little longer than Abbey had predicted, but in 1979, a group of hardcore conservationists founded Earth First!, inspired by The Monkey Wrench Gang. The group became infamous for direct action to stop logging and dams, and for its guerrilla-style stunts that verged on theater. In the spring of 1981, Earth First! activists unrolled a huge black plastic tarp down the side of the Glen Canyon Dam, inspired by a similar action from the book, as Abbey looked on.

There’s been a resurgence of interest in the radical tactics of the 1980s and ’90s. The podcast Timber Wars follows forest protests in the Pacific Northwest, and another called Burn Wild documents the story of the Earth Liberation Front — a group of monkeywrenchers that came to top the FBI’s list of “domestic terror” threats. “How far is too far to stop the planet burning?” asks the podcast’s host, Leah Sottile, drawing parallels to the modern climate movement.

Today, protesting a pipeline can come with a lengthy prison sentence. States have passed laws with harsh penalties for blocking pipelines and other “critical” infrastructure, with Utah recently becoming the 19th state to do so. The wave of state laws proliferated after the Dakota Access pipeline protests at Standing Rock in 2016.

While climate activists currently engage almost exclusively in peaceful civil disobedience and direct action, when law enforcement agencies mount a “repressive response,” the situation can turn violent, Fisher said. For example, the protests at Standing Rock were generally peaceful, only turning violent after security guards began threatening demonstrators with dogs and police began using water bombs and tear gas.

To be sure, disruptive activism also runs the risk of distracting from the issues at hand, Schneider-Mayerson said. Last fall, protesters with the group Just Stop Oil threw a can of Heinz tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers painting, which was protected by glass, to draw attention to the climate crisis. Instead, the conversation mostly revolved around whether the activists were helping or hurting the cause.

Still, these new novels, by casting radical activists in a sympathetic light, might alter what people think of as an appropriate response to global warming. “I wanted to comment on the fact that the way we talk about the environment and activism has changed because activists are seen as the enemy by governments,” VanderMeer, the author of Hummingbird Salamander, said in an interview when the book came out in 2021.

By showing what kinds of action are possible, storytellers “can shift the Overton window a bit in terms of which tactics are considered legitimate and acceptable,” Schneider-Mayerson said. With scientists calling for massive disruptions to the status quo to minimize the destruction of climate change, he argues that “radical” environmentalism isn’t so radical anymore.

“We’re all kind of locked in the hold of this ship, this fossil-fueled civilization that’s carrying us to a really terrible and unjust place,” Schneider-Mayerson said. “It’s pretty hard to blame people for trying to break out and make some noise.”