In the Mayan Ich Eq community in Hopelchen, Mexico, bees are considered relatives to the people. They also serve as an important part of the economy, cultivated by the Indigenous group for hundreds of years. But the beekeepers of the Mayan Ich Eq are different from what we typically think of as apiarists. Their relationship is reciprocal — the community members feed them and take care of them, and in turn, the bees don’t sting and give them honey.

A decade ago, Mexico granted Monsanto, a United States-based agricultural corporation, along with several other major companies, permission to buy land near Hopelchen in the Yucatan peninsula. The move went against Mexico’s constitution, which affirms for Indigenous people the right to be consulted in land use and economic decisions. Monsanto and the other companies first deforested the land, then started growing soybeans using chemicals and pesticides. The chemicals started making the bees sick. In Mayan Ich Eq tradition, beekeepers believe they feel what the bees do. So, when the insects became sick and started dying, the people did as well.

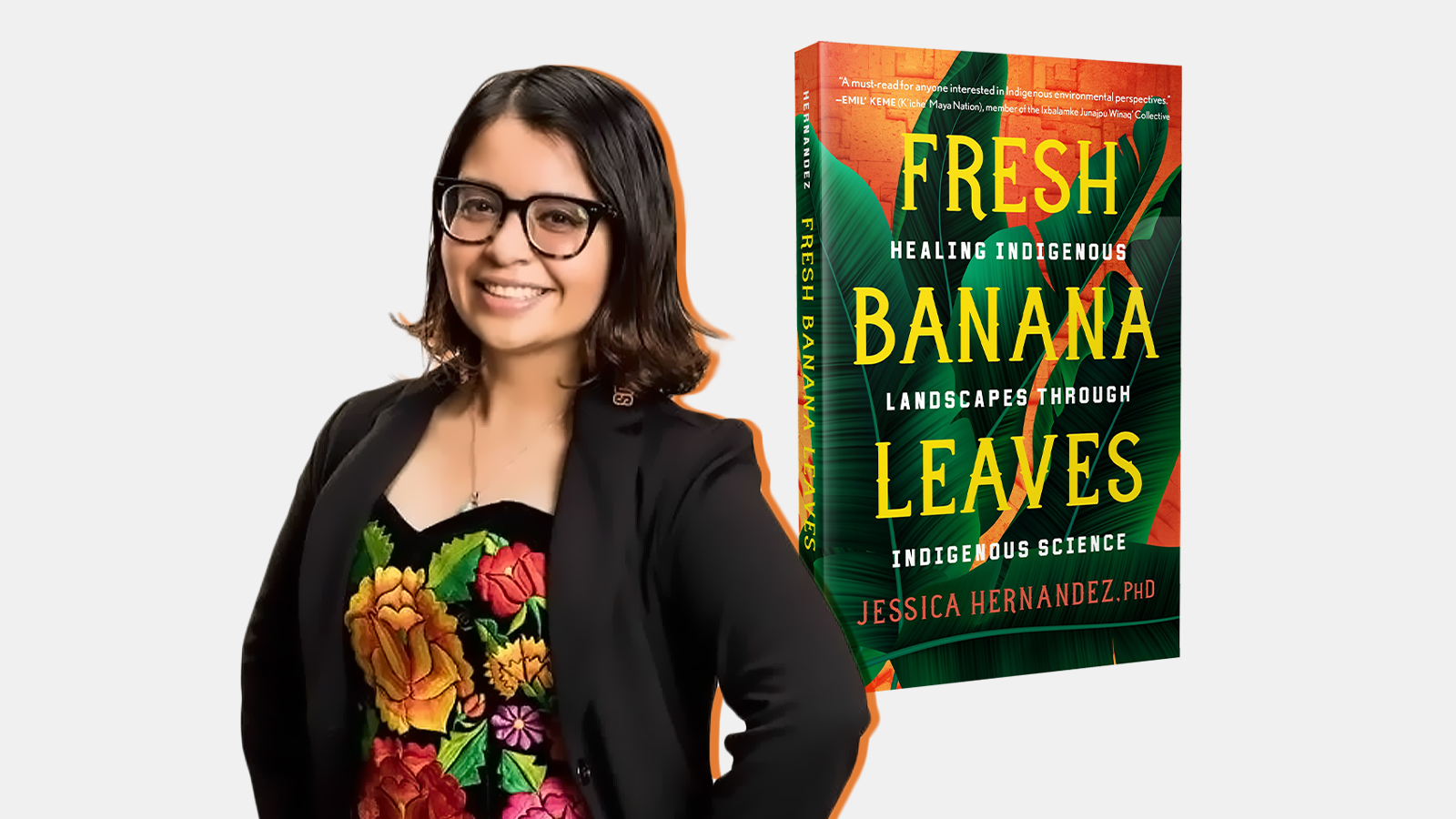

The situation is a reminder, says Jessica Hernandez, a Maya Ch’orti and Binnizá-Zapotec environmental scientist, that Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty and rights are not respected, even when codified into law. It is also a reminder of what is lost when Indigenous knowledge and science is ignored.

Hernandez chronicles the Mayan Ich Eq community’s fight to protect the bees and their people in her new book, Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science. In an interview with Grist, she talks about the urgent need to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into modern conservation, as well as respect tribal communities’ long-standing protection of the world’s biodiversity.

But the book isn’t just a how-to on fixing the conservation field, or relatedly, the climate crisis. It was also an opportunity for Hernandez to uplift stories that are often silenced or ignored, through translated interviews with her own family members, forced from their lands by conflict, and Indigenous land protectors across Central America. Next up, she hopes to publish the book in Spanish to make it accessible to more people.

Q. Why do you think Fresh Banana Leaves is needed now and what inspired you to write it?

A. Oftentimes, Indigenous knowledge is just nowhere to be found. There have been scholars who have advocated for the inclusion of Indigenous science [in academia], but oftentimes, when we talk about Indigenous knowledge and how that can help us heal our planet, especially as we undergo climate change, it’s limited. It’s a privilege to be able to write about it so that especially the younger generation can see themselves reflected, and understand that our knowledge also holds power and strength when it comes to healing our planet.

Q. You describe your family’s struggle with being forced from their ancestral lands, and the impact of that trauma on your environments. Can you talk about that experience?

A. My father was forced to join the Central American civil wars in the 1970s. It was an Indigenous resistance movement against oppression and oppressive tactics. But the army was using all this violence and technology that was provided by the United States and Canada. In order for him to survive, he had to leave his ancestral lands [in El Salvador].

We can see that parallel today, because a lot of Central Americans are having to flee their lands because of climate change impacts and ongoing violence.

Q. Why do you use the phrase “healing landscapes” instead of environmental justice?

A. Environmental justice is built on scholarly work in academia. Oftentimes when I talk to my elders, they don’t see their work as environmental justice because they always remind me that they don’t have an option. They don’t have a choice to do certain things. One of the reasons why I use healing is that even in our native languages, there are no words for conservation. We view it more as healing our environments or protecting them. Given the times that we’re living in, in order for us to heal our environments we also have to heal ourselves, especially from the ongoing oppression that we continue to face.

Q. You say that ecological grief is often overlooked in the climate change discourse. What does that mean, and why do we need to focus on it more?

A. Ecological grief ties back to the kinships that we hold as Indigenous peoples with our plants and animal relatives. The example I provide in the book is the milpas. The milpas are a central kind of holistic agricultural system that we have been able to maintain since time immemorial. Everybody takes care of the milpas, even children and elders. There is this kinship that is built around the milpas. And because of climate change impacts – flooding of the milpa or if you have extreme heat – there is a psychological grieving. You’re mourning or grieving the plant and animal relatives that you lost because of those extreme weather conditions. That grief comes from the fact that you are building a relationship with those animals and you consider them your relatives as well.

Q. In the book you highlight the community-based forest management happening in part of the Zapotec nation in Oaxaca, Mexico as a success story, compared to other more traditional outsider-run projects. What makes the Zapotec forestry initiative work, and what lessons does it provide scientists and conservation groups?

A. When we talk about conservation we forget to include the Indigenous peoples who will be impacted by the denial of gathering those resources. In many marine protected areas, for example, you are not allowed to fish, because they’re trying to conserve the marine ecosystems there. Other protected areas are led by scientists who don’t have a relationship with Indigenous peoples or who are only focused on protecting the animal, without looking at the holistic system.

It goes back to ecological grief.

We have that strong kinship with our forests, with our trees, because they’re part of us. It ties back to our creation stories and our ancestors. With the [Zapotec] forestry initiative, it [worked] because our people were integrated in the process and we were able to use Indigenous knowledge to manage and steward that forest. It’s holistic management, and integrated Indigenous peoples from the start.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.