After months of tense negotiation, a half-dozen states have reached an agreement to drastically cut their water usage and stabilize the drought-stricken Colorado River — as long as California doesn’t blow up the deal. The plan, which was developed without the input of Mexico or Native American tribes that rely on the river, seeks to stave off total collapse in the river for another few years, giving water users time to find a comprehensive solution for the chronically-depleted waterway.

On Monday, six out of the seven states that rely on the Colorado announced their support for steep emergency cuts totaling more than 2 million acre-feet of water, or roughly a quarter of annual usage from the river. The multi-state agreement, prodded into existence by the Biden administration’s threats to impose its own cuts, will likely serve as a blueprint for the federal government as it manages the river over the next four years, ushering in a new era of conservation in the drought-wracked Southwest. While the exact consequences of these massive cuts are still largely uncertain, they will almost certainly spell disaster for water-intensive agriculture operations and new residential development in the region’s booming cities.

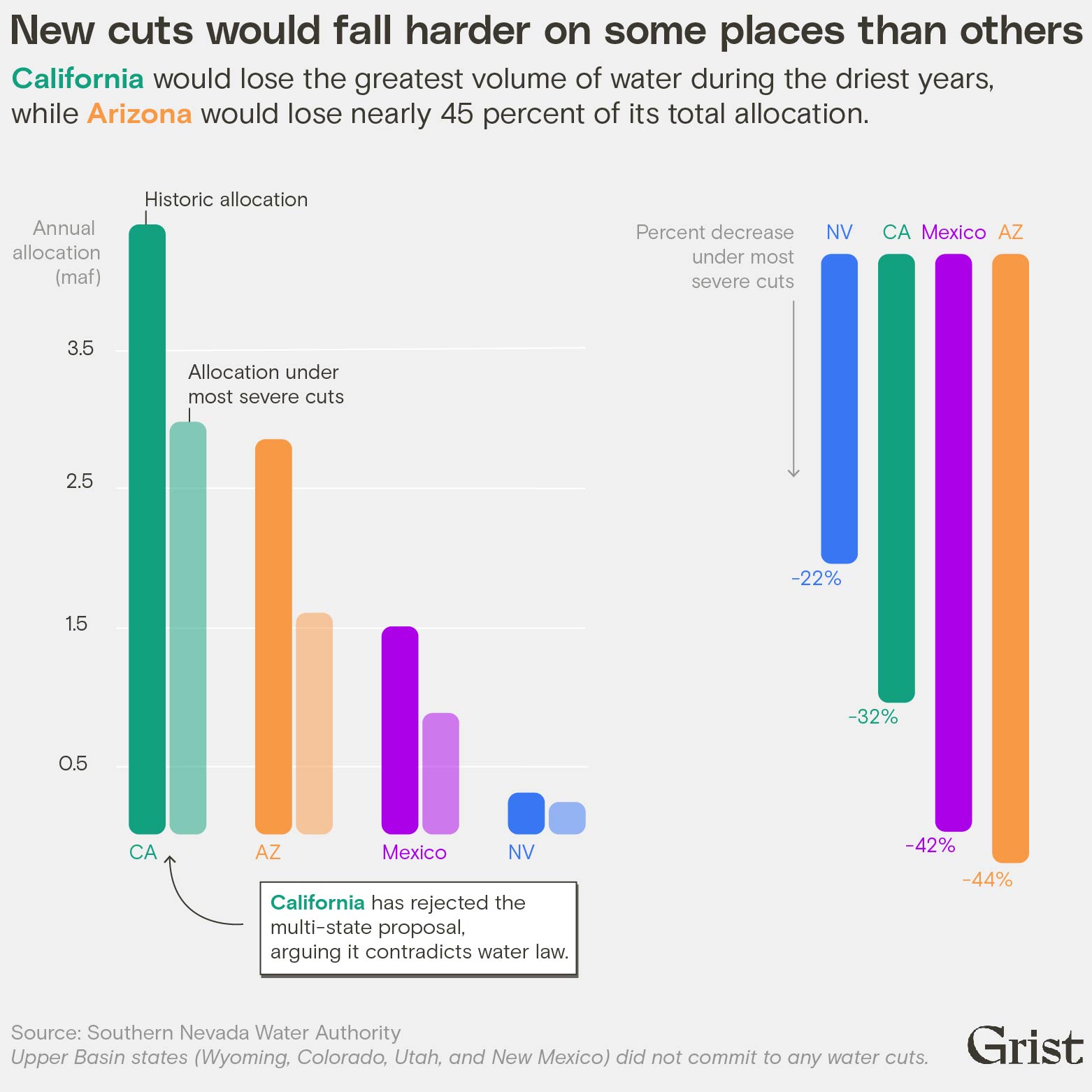

But California, which takes more water than any other state, has rejected the proposal as too onerous, instead proposing its own plan with a less stringent scheme for cutting water usage. If the federal government does adopt the six-state framework, powerful farmers in California’s Imperial Valley may sue to stop it, setting up a legal showdown that could derail the Biden administration’s drought response efforts.

Nevertheless, the general consensus on pursuing immediate, dramatic water cuts is unprecedented.

“It puts something down on the table that we haven’t had before,” said Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno who studies the Colorado River. “The states are saying, ‘We recognize just how bad it is, and we’re willing to take cuts much, much sooner than we had previously agreed to.’”

The Colorado River has been oversubscribed for more than a century thanks to a much-maligned 1922 contract that allocated more water than actually existed, but it has also been shrinking over the past 20 years thanks to a millennium-scale drought made worse by climate change. Last year, as high winter temperatures caused the snowpack that feeds the river to vanish, water levels plummeted in the river’s two key reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, threatening to knock out electricity generation at two major dams.

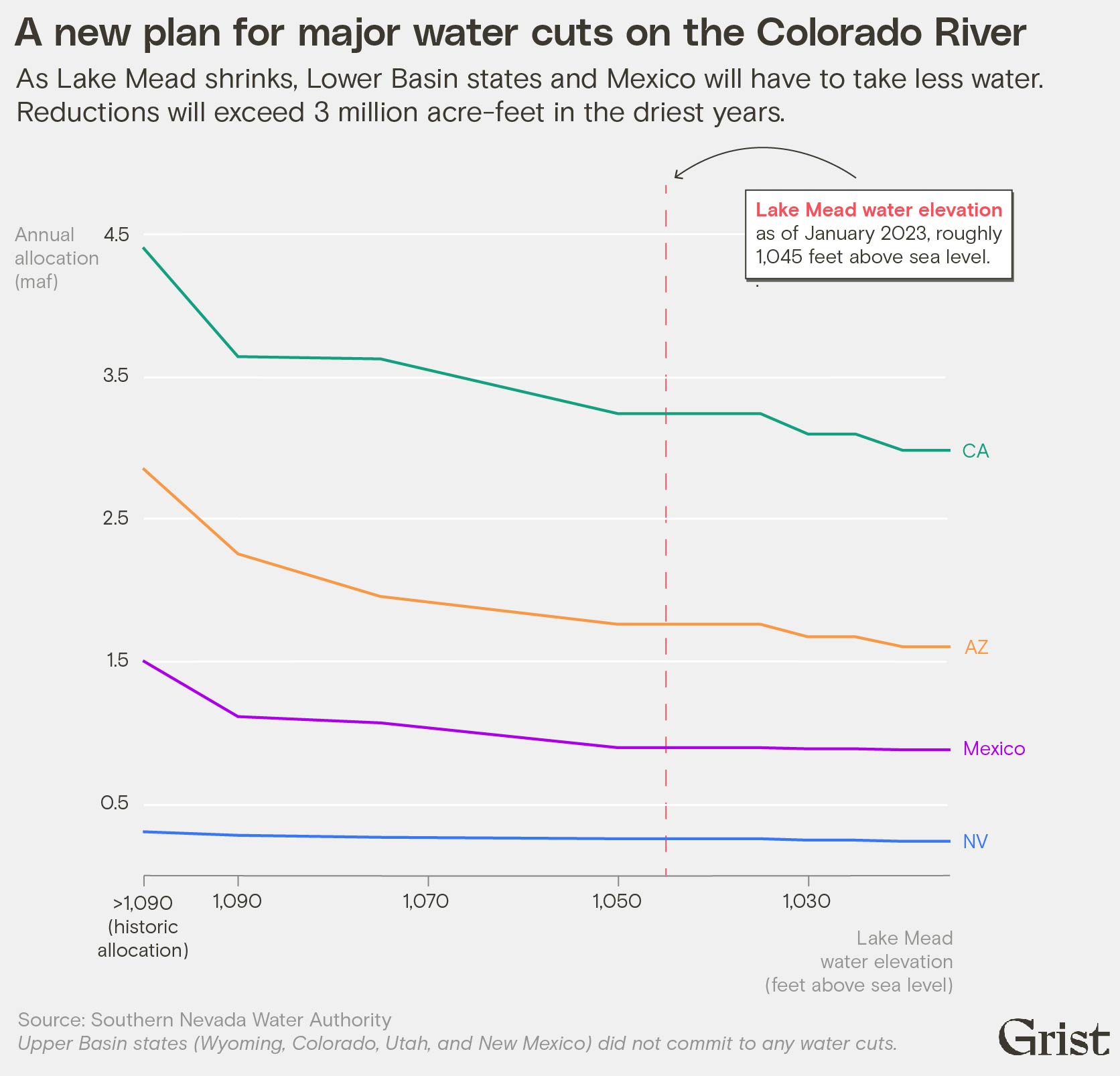

Federal officials intervened in June, ordering the seven Colorado River Basin states to find a way to reduce their annual water usage by between 2 and 4 million acre-feet. This was a jaw-dropping demand, far more than the states had ever contemplated cutting, and they blew through an initial August deadline to find a solution. The feds upped the pressure in October, threatening to impose unilateral cuts if state officials didn’t work out a solution.

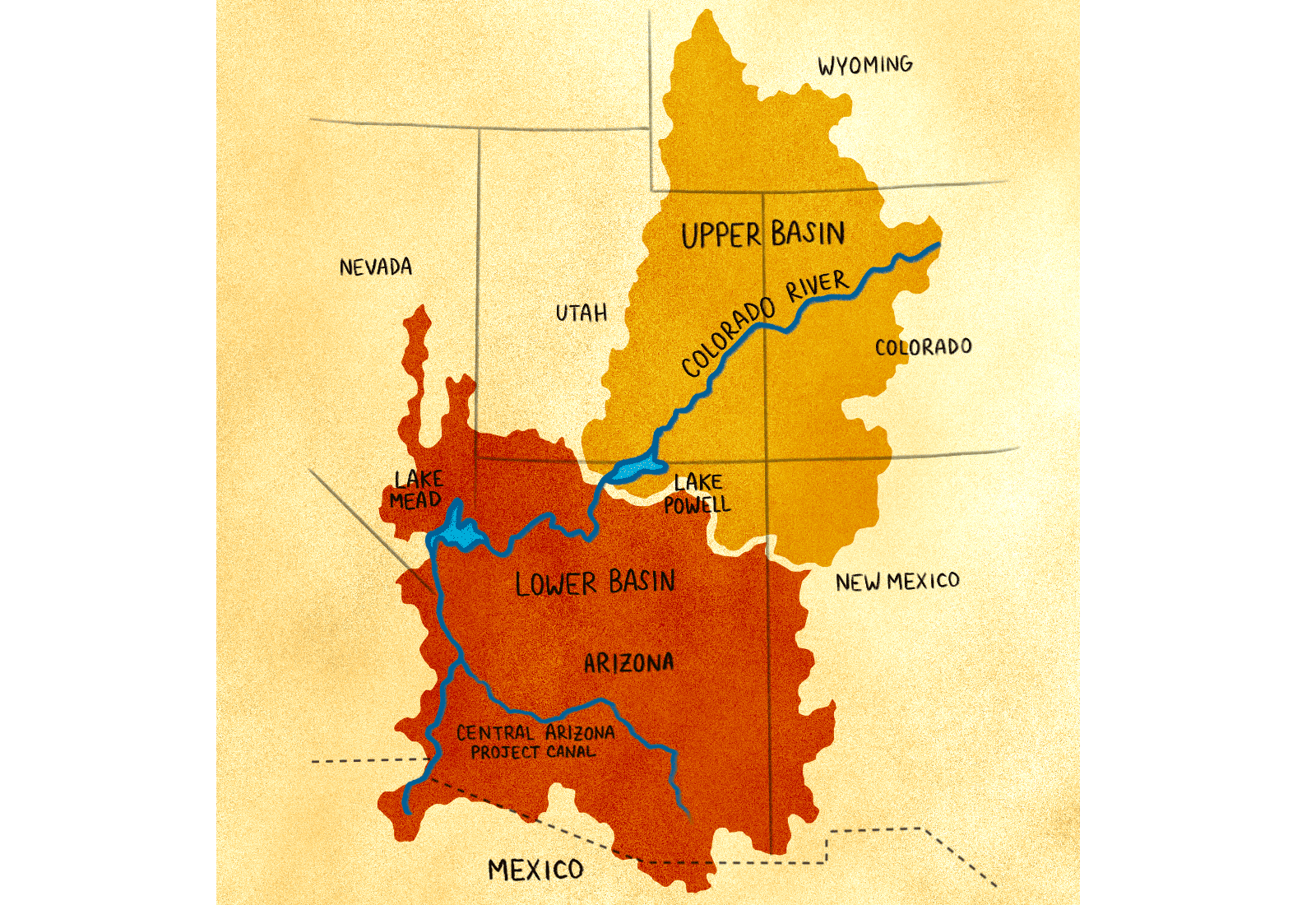

As the interstate talks proceeded, long-buried conflicts began to resurface. The first major conflict is between the Upper Basin states — Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah — and the Lower Basin states: Nevada, Arizona, California, and Mexico. The Upper Basin states argue that the Lower Basin states should be the ones to cut water in response to the drought. These states use much more water, the argument goes, and they also waste a lot of water that evaporates as it flows downstream through reservoirs and canals. The Lower Basin states, meanwhile, argue that no states should be exempt from cuts, given the scale of reductions needed.

The other main conflict is between Arizona and California, the two largest Lower Basin water users and the main targets of future cuts. California’s water rights trump Arizona’s, and therefore the Golden State argues that Arizona should shoulder almost the whole burden of future cuts. Arizona argues in turn that its farms and subdivisions have already cut their water usage in recent years as the drought has gotten worse, and that water-rich farmers in California should do more to help.

In the middle of these warring parties is Nevada, which takes only a tiny share of the river’s water and has emerged as the Switzerland of the Colorado River system over the past year. Water officials from the Silver State have been trying since late summer to broker a compromise between the Upper and Lower Basins and between Arizona and California, culminating in an intense session of talks in Las Vegas in December.

The talks were only partly successful. Officials managed to work out a framework that meets the Biden administration’s demands for major cuts, bringing an end to a year of uncertain back-and-forth. The proposal would cut more than a million acre-feet of water each from Arizona and California during the driest years, plus another 625,000 acre-feet from Mexico and 67,000 acre-feet from Nevada, adding new reductions to account for water that evaporates as it moves downstream. In return for these Lower Basin cuts, the Upper Basin states have agreed to move more water downstream to Lake Powell, helping protect that reservoir’s critical energy infrastructure — but they haven’t committed to reduce any water usage themselves.

“It seems like the Lower Basin states conceded to the Upper Basin,” said Koebele. An earlier version of the six-state proposal called for the Upper Basin to reduce water usage by a collective 500,000 acre-feet, but that call was absent from the final framework.

While the fight between the Upper and Lower Basin states appears neutralized, the conflict between the Lower Basin’s two biggest users is ongoing. Around 40 percent of the agreement’s proposed reductions come from California, where state officials have slammed it as a violation of their senior water rights, derived from a series of laws and court decisions known collectively as the “law of the river.”

“The modeling proposal submitted by the six other basin states is inconsistent with the Law of the River and does not form a seven-state consensus approach,” said J.B. Hamby, California’s lead representative in the talks. Hamby argued that penalizing California for evaporation losses on the river contradicts the legal precedent that gives California clear seniority over Arizona.

Officials from the Golden State released their own rough framework for dealing with the drought on Tuesday. The plan offers a more forgiving schedule than the six-state framework, saving the largest cuts for when Lake Mead’s water level is extremely low, and it forces more pain on Arizona and Mexico. The framework only requires California to cut around 400,000 acre-feet of new water, which the biggest water users already volunteered to do last September in exchange for federal money to restore the drought-stricken Salton Sea. Water users in the state haven’t made new commitments since.

If the Biden administration moves forward with the plan, it may trigger legal action from the Imperial Irrigation District, which represents powerful fruit and vegetable farmers in California’s Imperial Valley. The district sued to block a previous drought agreement back in 2019, and its farmers have the most to lose from the new framework, since they’ve been insulated from all previous cuts. The state’s other major water user, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, has signaled tentative approval for the broad strokes of six-state formula, indicating that a compromise between the two plans might be possible, although it’s not clear such a compromise would please Imperial’s farmers.

“I don’t see how we avoid Imperial suing, other than a bunch of big snowpack,” said John Fleck, a professor of water policy at the University of New Mexico. In response to a request for comment from Grist about litigation, an Imperial spokesperson emphasized the need for “constructive dialogue and mutual understanding.” If Imperial did sue and win, the outcome would likely be even further pain for Arizona and Mexico, where farmers and cities are already struggling to deal with previous cuts.

Koebele told Grist that while the exact numbers may change, federal officials will likely adopt some version of the six-state proposal by the end of the summer. Even a modified version would alter life in the Southwest over the next four years, imposing a harsh new regime on a region whose water-guzzling produces a substantial portion of the nation’s vegetables and cattle feed. Major cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Tijuana would also see water cuts, threatening growth in those places.

Steep as the new cuts are, though, they will only last until 2026, when basin leaders will gather again to work out a long-term plan for managing the river over the next two decades. Unlike the current round of emergency talks, that long-term negotiation will include representatives from Mexico and the dozens of Native American tribes that rely on the river.

Koebele said that the questions in those talks will be even more difficult than the ones the states are debating now. Instead of just figuring out who takes cuts in the driest years, the parties will have to figure out how to apportion a perennially smaller river while also fulfilling new tribal claims on long-sought water rights. The present crisis has only delayed progress on those bigger questions.

“Because of the dire situation, we’ve really had to turn our attention to managing for the present,” she said. “So these actions feel more like a Band-Aid to me.”