This story was originally published by the Texas Tribune and is republished with permission. This article is part of a series published by The Texas Tribune examining the state’s deteriorating water infrastructure.

Tom Bailey had just finished his morning routine of checking the town’s three water well sites when he got a call from a resident: Water was coming out of the road.

Bailey, public works director for this small, East Texas town, hopped in his pickup truck and drove to the scene on a bumpy road that sits behind the high school.

The entire road was wet.

“Water was just boiling up in the middle of the road,” Bailey said. “Not normal. Not normal at all.”

As water continued to flow down the street, Bailey and Cody Day, a water operator who works under Bailey, jumped back in the truck and drove into town to pick up a mini excavator from storage. They returned and dug into the ground to find the water source: a leaking pipe.

That one leak turned into a saga. Every time Bailey and Day would make a repair, the line would break somewhere else. Customers in the area lost water intermittently for three days.

“I felt disappointed in myself,” Bailey said. “If it’s my repair and my repair failed, then I did something wrong.”

The repeated line breaks were not under Bailey’s control. Installed in the 1960s, the pipes are part of a larger, deteriorating underground infrastructure that Bailey was handed when he took over as the town’s public works director in January. His start date followed a disastrous water crisis that left Zavalla’s roughly 700 residents without drinking water for 10 days and forced the town’s water department to work on Christmas Eve.

“There’s so much in disrepair,” Bailey said. “It’s a daily balance.”

Zavalla’s struggles are not unique. Across the state, from the arid plains of West Texas to the Piney Woods along the Louisiana border, water and wastewater infrastructure is failing — if it exists at all.

The Lone Star State’s drinking water infrastructure barely received a passing grade in a 2021 report from the American Society of Civil Engineers, a low mark for the nation’s second-most-populous state with a reputation for bravado. The multibillion-dollar situation has grown only more dire, as the underground problems erupt into Texans’ everyday lives.

In 2021, the state reported more than 30 billion gallons of water lost due to breaks or leaks that were fixed, according to the Texas Water Development Board, a state agency that tracks the state’s water supply. Another 100 billion gallons of water loss can be attributed to faulty infrastructure and other statewide issues, Texas officials said. That loss cost the state more than $266 million.

The actual amount of water lost is likely greater. While water audits are required from all agencies that have more than 3,300 connections or receive money from the water board, only a fraction of those entities are captured because either the local water agencies didn’t report or the state found inaccurate data in what was submitted and rejected the audit. For example, only about 800 agencies are represented in the 2021 report. More than 4,000 are expected to submit data every year. Agencies that do not report face few, if any, consequences: The water board can withhold financial support until a water provider has submitted its audit.

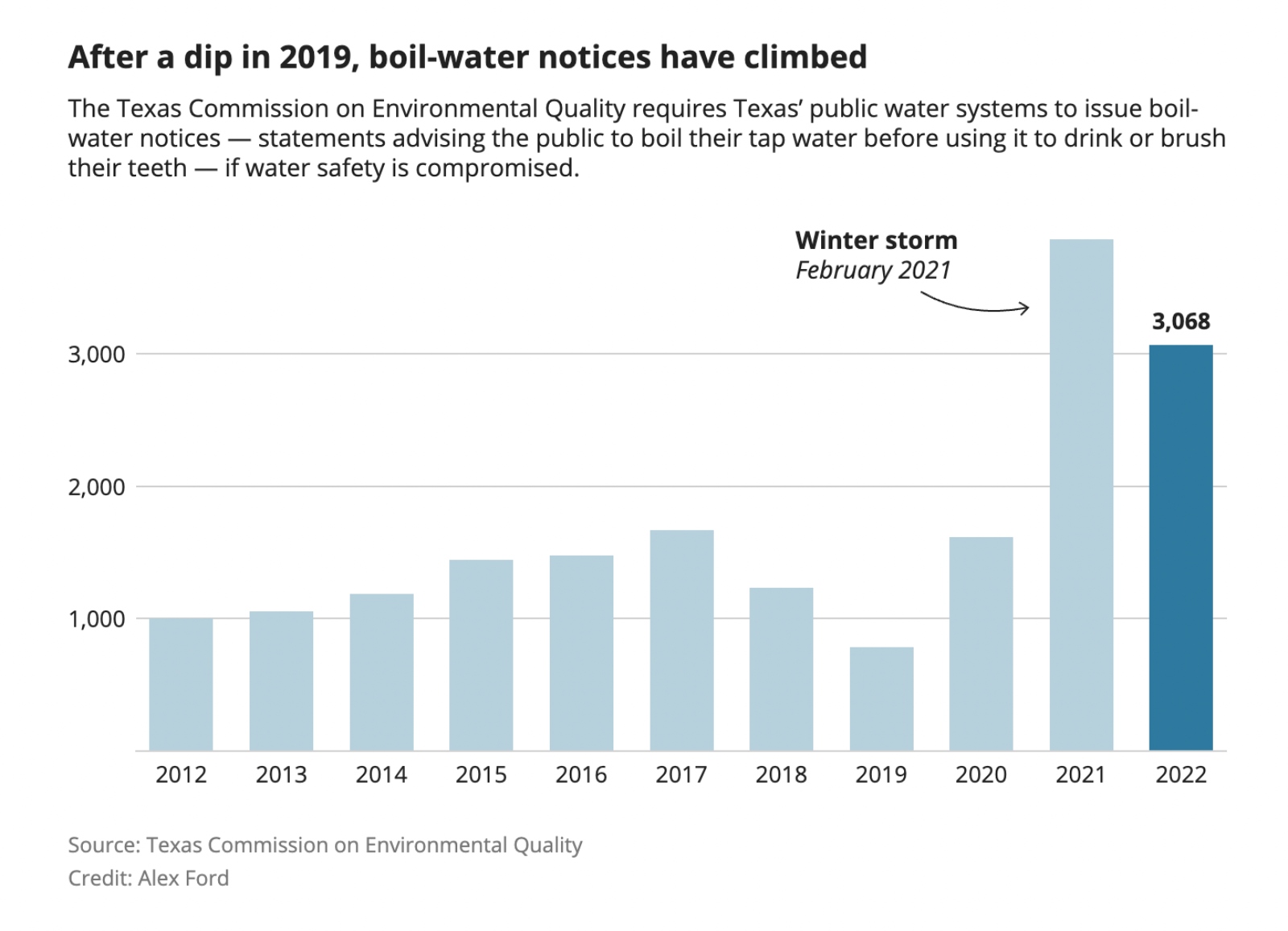

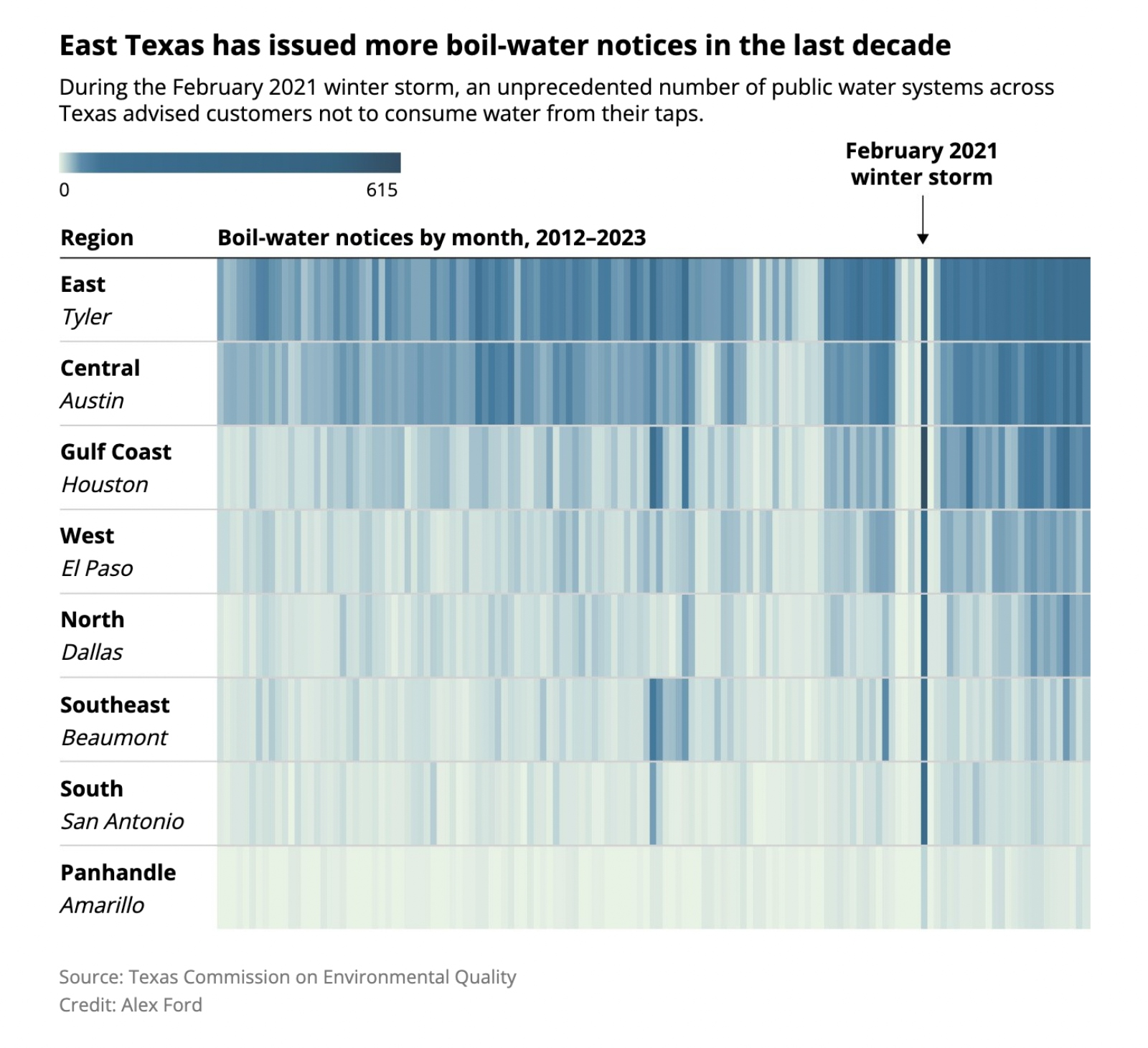

Deteriorating water infrastructure contributed to an extended water outage in Odessa last summer and continues to fuel a growing number of boil-water notices statewide. Over the last five years — between 2018 and 2022 — water entities have issued 55 percent more boil-water notices than they did over the previous five-year period, according to a Tribune analysis of data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

The problem is exacerbated in rural areas — where population densities tend to be lower and the pipes tend to be older, some dating back to the 1890s. With a smaller tax base, rural communities have less money to spend on fixing repairs or upgrading water infrastructure. Texas has the largest rural population in the country. Nearly 4.8 million people live outside a metro area in Texas, according to the latest estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The state continues to grow rapidly, and although much of that growth is concentrated in metro areas, it is beginning to spread into rural counties, including those just outside of Houston and Dallas. The booming population places more pressure on the state’s vital resources, including water.

As Texas’ population continues to grow at a record pace — including in new developments across rural Texas — the question is not if, but when, the pipes will break.

Texas’ water infrastructure issues mirror those across the nation. From Jackson, Mississippi, to Lincoln Park, Michigan, water systems are under duress.

While water infrastructure is traditionally a local issue, water advocates and cash-poor municipalities hope the state will take a larger role in investing in past-due upgrades. And state lawmakers have a unique opportunity to address the state’s crisis before they leave the Capitol at the end of the legislative session. Texas lawmakers entered the legislative session with more money at their disposal than they ever had before, thanks to a historic budget surplus of $32.7 billion. Texas is expected to receive approximately $2.5 billion of federal dollars earmarked for water infrastructure through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed into law by President Joe Biden in 2021.

And as Texas gets hotter, drier, and more populated, state lawmakers are paying attention to the collapsing, aging systems that are meant to provide safe drinking water to 30 million Texans.

Lawmakers are keen to act. Texas senators unanimously approved legislation that would create a new water supply fund and pay for upgrades to water infrastructure, with some funding reserved for communities with fewer than 150,000 people.

The amount of money allocated for the legislation is yet to be determined. The Senate has set aside $1 billion and the state House, which must co-sign on any legislation, has proposed a substantially higher figure: $3 billion.

Water advocates and stakeholders say the bill is both a crucial step and insufficient to meet the growing statewide need.

Texas needs an estimated $61.3 billion in infrastructure investment over the next 20 years, according to a national survey by the Environmental Protection Agency released in March.

Jeremy Mazur, a senior policy analyst for the nonpartisan advocacy group Texas 2036 who has studied the state’s water needs, put the federal and state investment this way: “It’s going to be a drop in the bucket compared to the long-term cost.”

Boil-water notices bring to light water infrastructure woes

Two days before Thanksgiving, dozens of Zavalla residents packed into City Hall for an emergency town meeting. What had begun with low water pressure earlier in the month turned into a complete outage that caused schools and businesses to close. The town’s public works director resigned, and no city employee had the appropriate license to operate the town’s main well. For longtime Zavalla residents, the problems were bad but nothing new.

“We’ve always had water problems,” said Brenda Cox, a former City Council member who will take office as the town’s mayor this month. “The bottom line is, we need a quick fix. We’ve got to have water.”

The Texas Division of Emergency Management sent pallets of bottled water to Zavalla and deployed the Texas A&M Public Works Response Team to help. They fixed leaks and checked water lines for a loss of pressure. By Thanksgiving Day, water was restored for most residents, but a boil-water notice remained in effect. The working-class town 25 miles outside of Lufkin and known for its proximity to the popular fishing destination of Sam Rayburn Reservoir was thrust into the public spotlight.

Boil-water notices are among the most public manifestations of the state’s water crisis, and they are increasing rapidly. In 2021, 3,866 boil-water notices were issued across the state — the highest number in the last decade, according to data self-reported by water agencies across the state to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. That high number likely was linked to the 2021 winter storm Uri, which caused pipes to freeze and burst across Texas.

The number of notices dropped slightly to 3,068 in 2022. That number is significantly higher than the 10-year average, and numbers have remained high in 2023. During the first three months of this year, 759 notices have been issued, or an average of about eight per day.

Boil-water notices are issued for a variety of reasons and do not necessarily mean water is contaminated. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality requires water entities to issue boil-water notices under circumstances in which public health could be compromised, including when water pressure drops below 20 pounds per square inch. A loss in pressure can indicate a leak, and leaks can allow foreign particles or contaminants to enter the water supply.

Leaks are becoming increasingly common in part because of aging infrastructure. Old pipes are more vulnerable to breaks and damage during extreme weather events. And those events are becoming more frequent because of climate change, experts say.

Last year, Texas faced its worst drought in more than a decade. About 75 percent of the state is still experiencing drought conditions, according to U.S. drought monitor, and those conditions will persist this summer. On the other end of the spectrum, ice storms are also common occurrences in Texas. In February, a heavy winter storm caused widespread power outages in much of Central and East Texas and raised questions about whether Texas’ infrastructure is equipped to handle such extreme weather.

In Crockett, one of the oldest county seats in Texas, water workers at Consolidated Water Supply Corporation have dubbed one particularly troublesome area “mini tornado alley.” Tornadoes can bring strong wind gusts along with lightning and floods that can damage water infrastructure, including storage tanks and distribution systems. Ruptured service lines can decrease water pressure and result in more boil-water notices.

In April 2019, a devastating tornado with peak wind speeds of 140 mph struck northeast of Crockett. The storm uprooted one of Consolidated’s water lines, and post-storm cleanup damaged water mains, said Amber Stelly, general manager of the water agency. Three boil-water notices were issued in connection with the storm.

Last March, a tornado struck between two of Consolidated’s water plants. The water system issued two boil-water notices that day due to low-pressure systems and water outages. The water tanks were spared, Stelly said, but severe weather keeps everyone on edge.

“What I lose sleep over is storms,” said plant operator BJ Perry, who worked for the water department in Elkhart — a town about 25 miles north of Crockett — before joining Consolidated. “It’s like, oh my god, here we go again.”

On a Friday afternoon in March, Perry was nearing the end of his shift when a tornado warning sounded an alarm on Stelly’s iPhone. Perry had just returned from investigating a chlorination issue and was reporting his findings to Stelly.

State environmental guidelines say that chlorine levels of 0.2 milligrams per liter must be maintained throughout the drinking water treatment process and distribution system. Water systems are supposed to issue boil-water notices when levels fall below that threshold. Chlorine is a common disinfectant used to rid drinking water of bacteria or other microorganisms.

Perry detected signs of a possible drop in chlorine levels. The likely culprit: a leak. If he could get the levels in check, he could avoid issuing a boil-water notice. Consolidated issued 68 boil-water notices in 2022, the highest number issued by a public water entity last year and has led the state in the number issued in March, according to TCEQ data.

Stelly said notices typically apply to certain areas, but they still go out to all customers and can unnecessarily cause alarm.

“I want people to heed warnings,” Stelly said. “I won’t want them to ignore them because they are blasted with them all day.” She said she’s working on a system that would better target the notices.

Barely keep up with growth

Water is the never-ending task on Randy Criswell’s daily to-do list as Wolfforth’s city manager.

Every day, he must manage the delicate interplay among quantity, quality, and the system that is supposed to ensure both.

“Not one single day has passed that it doesn’t come up,” Criswell said of his 15 months in office. “Some days it’s the majority of my time, if not a substantial portion of it.”

Criswell inherited the Lubbock suburb’s worst-kept secret — the town’s water problems. Over a 10-year period, Wolfforth received 362 violations for exceeding the legal amounts of fluoride and arsenic, a known carcinogen.

Wolfforth was using water from private wells supplied with water from the Ogallala Aquifer, which does have both contaminants. As a way to make the water safer for residents and regain their confidence, Wolfforth opened its current water treatment plant in 2017 specifically to lower the arsenic and fluoride levels.

“The Ogallala water in this part of the state is not the greatest quality,” said Criswell, who took office in January 2022. “A lot of it has fluoride concentration levels that are not where the EPA and TCEQ would like to see them.”

Wolfforth isn’t the only town that has higher levels of the carcinogen. A 2016 report found that 65 Texas water systems, primarily in small towns or rural areas clustered in West Texas and the near the Gulf Coast, contained excessive levels of arsenic, exposing more than 82,000 Texans. Water in Seagraves, 65 miles southwest from Lubbock, had arsenic levels that were three times over the health standard, making it unsafe for the 2,396 residents.

Subpar water infrastructure makes the arsenic problem — which is largely unavoidable, particularly in the endless plains of West Texas — worse.

Existing in pockets of dirt and rocks, arsenic is essentially shaken loose by natural causes and human activity, such as traffic or construction. It’s then released into groundwater sources, such as the aquifer. It’s also found in industrial products and chemicals that are used in the region.

Older pipes that break and develop small cracks also leave the water vulnerable to harmful contaminants. The risk could get worse, depending on what the water lines and their bindings are made of.

Since some cities were developed in the late 19th century, construction workers made do with whatever materials they had nearby.

“Sometimes their water supply piping or stormwater piping might have actually been made out of wood,” said Ken Rainwater, a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. “They would make cylindrical pipes out of planks because that’s what they had on hand.”

Rainwater said other materials included cast iron, copper, and lead — a new EPA assessment found that 647,000 water lines in Texas are made of lead, accounting for 7 percent of the state’s total water infrastructure.

Keeping track of endless miles of water lines can be difficult as there is no database tracking the age or materials of pipes, or even where exactly they are located underground. While some cities in Texas have managed to create such mapping, many small and rural communities have understaffed city offices that can’t commit resources to intensive, yet necessary, mapping.

Melinda Luna with the Texas ASCE often finds herself piecing together the lost history of the state’s water infrastructure. It’s a daunting task. When she asks local officials for maps of their water lines for projects, she is sometimes met with confused looks.

“If cities were built 100 years ago and they haven’t touched them since, then it’s out of sight, out of mind,” Luna said.

Luna’s research has shed light on some of the state’s oldest pipes, such as wooden pipes in Waco, Tyler, Eastland, Laredo and Weslaco. Most recently in 2019, a wooden water pipe in the Panhandle town of Pampa was discovered that had originally been installed in the 1890s.

“Until cities get a true inventory of their stuff out there, they don’t really know what’s there,” Luna explained. “Once you have an inventory, you can maybe manage the madness a little bit easier.”

Back in Wolfforth, Criswell is hopeful he has found a way to manage the madness. The filtration system in his area’s treatment plant is designed to clean the water through thousands of thin polymer membrane layers. The layers could have cost the city a pretty penny — they are worth $35,000. However, they were reclaimed from a plant in El Paso.

The city is in the process of designing another water treatment plant, this one to clean the water and to hold more water that the city is bringing in from other sources. It’s made city officials more optimistic about the future of their home.

“Soon, we’ll have survived a crisis in Wolfforth that everybody’s going to come out on the other end of OK,” Criswell said.

In Zavalla, a small rate increase could go a long way

On a Monday evening in April, Bailey — Zavalla’s public works director — drove back up the road where he had tended to a series of leaks three weeks earlier. His truck jostled over potholes that residents have been asking him to patch up. Bailey oversees water and wastewater — along with the town’s infrastructure needs like road repairs. Bailey and Day patched up holes on that road using gravel.

It was never meant to be a long-term fix, Bailey said, but it was the most he could do.

“I’m on a limited budget,” Bailey said. “I only have so much money a year for patching.”

Down the road, an orange traffic drum marked the spot where the leaks had occurred. The spot was still damp.

“I hope it’s not leaking,” Bailey said. “But it’s awfully soft.”

A mile away at City Hall, the town’s council was set to discuss changes to the water department’s payment plan guidelines.

In February, the council approved a $4 per month increase on water and sewer rates, the first rate increase they had adopted in decades. It was a small victory for Bailey, who hopes the added revenue will help the town create a contingency fund for infrastructure repairs or future expansions.

Mayor pro tem Kim Retherford said some residents have not paid for water in years and have accumulated an over $800 water bill. She urged the council to change the town’s payment plan guidelines, which have previously allowed residents to repeatedly defer payment on their water bills.

“On the paperwork we have, there is not a place where you can say ‘this is how much you owe, this is when you’re gonna pay it, and this is how,” Retherford said to the council. “We’ve got to give [the water department] what they need to push forward.”

After nearly thirty minutes of debate, Retherford called for a vote on the new policy. Under the new guidelines, customers who enter into a payment plan would be expected to pay off their bill within four months. With three city council members in favor, none against, and one member abstaining, the new policy passed and went into effect immediately — another victory for Bailey.

Disclosure: Texas 2036 has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations, and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.