This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A handful of weary residents gathered at the windowless Randolph church to mull over the latest effort by an electric utility to expand its power station—a polluting gas-fired plant next door to the community that the state regulator has blocked on environmental and health grounds.

Randolph is a historic Black community in central Arizona flanked by railroads and heavy hazardous industries, a small dusty place where residents are exposed to some of the worst air quality in the state while lacking basic amenities like fire hydrants, trash collection, and healthcare.

Last year, the community celebrated a historic win when the state regulator rejected a proposal by the public utility Salt River Project (SRP) to more than double the size of its power plant, ruling that it would cause further harm to Randolph residents and was not in the public interest.

It was major victory for clean energy and environmental justice in Arizona, according to the Sierra Club, the environmental group which condemned the proposed expansion as “textbook environmental racism.”

But SRP has refused to take no for an answer, and residents fear that the state regulator might reverse its decision.

“We won, they lost, but they won’t accept it, and keep coming back. This is not democratic,” said Ron Jordan, 77, whose family has lived in Randolph since in the 1930s. “They are dangling goodies in front of us, but the community doesn’t want it, we already have too much pollution. This isn’t right.”

At a recent community meeting held at the modest church, SRP offered to finance a new community center, air quality monitoring, and $50,000 in landscaping and signage among other projects if residents dropped their opposition to power plant expansion.

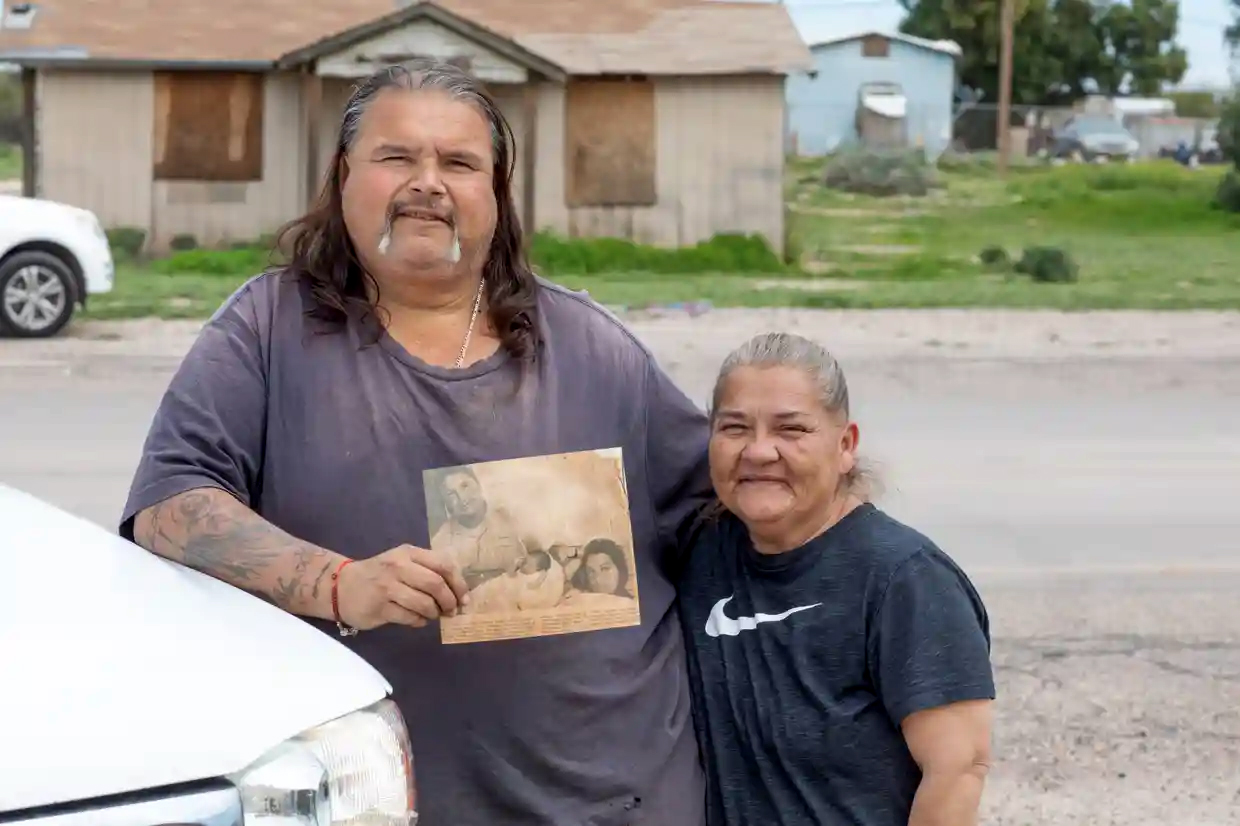

“We’re not giving up no matter what they offer,” said Guadalupe Felix, 45, whose family have lived in Randolph for three generations. “This plant is going to kill us, we’re already suffocating.”

The community says it won’t back down, but nationwide utilities have a track record of getting what they want, according to David Pomerantz, director of the Energy and Policy Institute (EPI). “Refusing to take no for an answer is incredibly common.”

Randolph is an unincorporated town in Pinal County first settled in the 1920s and 30s by mostly Black families from Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas who came to pick cotton in the Gila River valley. It was one of the only places Black families could buy property, and by the 1960s the close-knit agricultural community, which was also home to Mexicans and Native Americans, boasted thriving stores, bars, churches and gas stations.

Mechanization of the cotton industry led to the community’s economic and population decline, after which the nearby town of Coolidge began annexing the land around Randolph and converted it into an industrial area.

Today, only 150 or so residents live in an area the equivalent of seven football fields long by three fields wide, some in houses or plots purchased by their ancestors. There’s no store, no bar, no gas station and no park, just the church with a single lofty palm for shade.

The agricultural fields and desert plains where children would ride their bikes and chase roadrunners are long gone, and Randolph is now virtually surrounded by polluting infrastructure including gas plants, pipelines, a hazardous waste site and a steel company contracted to manufacture Donald’s Trump’s border wall.

The community is literally surrounded by cumulative and acute hazards.

Pinal County has some of the worst air pollution in Arizona, according to the American Lung Association and the Environmental Protection Agency. It is also bearing the brunt of the climate crisis with farmers forced to leave fields fallow or sell them off, many to solar farms, due to ongoing drought and water shortages. In August 2021, a gas pipeline explosion threw Randolph residents out of bed, igniting a huge fireball that killed farm worker Luis Alvarez and his 14-year-old daughter Valeria.

Part of the problem is the gas-fired power station, which lights up at night, hums like an airport, and spews out toxins and greenhouse gases from a dozen towering stacks. SRP purchased the plant in 2019, and two years later sought environmental approval from the Arizona corporation commission (ACC) for an almost a billion-dollar 820MW expansion.

The ACC is the state utility regulator responsible for approving SRP’s power plants and transmission lines, as well as rate hikes and new energy projects for private energy, water and telecommunication utilities. Every state has a version of the ACC, most commonly referred to as a public utilities commission (PUC).

As the community, the Sierra Club and others organized against the plant expansion, SRP announced plans to help finance road paving, landscaping projects, and a scholarships and job training program, as well as an attempt to get Randolph recognized as a national historic place.

In April 2022, the ACC rejected SRP’s expansion plan after concluding that the power company had failed to consider viable green energy alternatives such as solar and battery storage before pursuing the power plant expansion—which would worsen air quality especially for Randolph residents who live next door. (The commission rejected a recommendation by its power plant and line siting committee to grant the environmental certificate.)

SRP requested a new hearing, which the ACC denied. The utility then filed—and lost—a lawsuit at the Maricopa county superior court. “The [ACC] determined that the need for the proposed project is outweighed by its environmental impact. SRP has not shown that decision to be unlawful or unreasonable,” the court ruled in January 2023.

SRP still wouldn’t take no for an answer, and has since petitioned the state supreme court to hear the case, and persuaded the ACC to reopen discussion on the expansion.

“SRP is used to getting its way, and it’s pushing on all fronts. The ACC has a huge impact in people’s lives, but the process wears communities down, it’s never over,” said Sandy Bahr, director of the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon chapter. “It’s heartbreaking for the Randolph folks who finally felt that their voices had been heard.”

The ACC was established in the state constitution and, unlike PUCs in other states, it is also responsible for railroad and pipeline safety, incorporating businesses and regulating securities. In most states, PUC commissioners are appointed by the governor, but in a quarter of states, including Arizona, the commissioners are elected directly by voters.

“Utilities typically try to get a new decision from a PUC when they don’t like the original one about a rate hike or a new gas plant. They will wait it out [for new commissioners] or try to circumvent the commission altogether if they think the legislature will be friendlier to their cause,” said Pomerantz of the EPI.

Last year, Indiana’s PUC, the utility regulatory commission, approved two new gas plants—three years after rejecting the power company’s initial proposal for failing to adequately consider renewables. In Virginia, state lawmakers who have received substantial donations from Dominion Energy, which also spends big in Washington, recently attempted to pass legislation to increase the company’s authorized profit margin despite households struggling to pay their bills.

Utilities spend big on state politics and in the 2020 election cycle, investor-owned energy utilities contributed almost $12 million to influential political organizations such as the Republican and Democrat governor and attorney general associations, according to an EPI analysis. To get what they want from Congress, electric utilities spent $347 million on lobbying Washington in the past three years, including $3.4 million by SRP affiliates, according to Open Secrets.

Utilities are known to have directed large sums to influence campaigns in states with elected commissioners including Georgia, Louisiana, and Arizona.

In Arizona, the ACC is the primary governmental body for tackling the climate crisis. In 2006, it established an energy standard that mandated utilities to generate at least 15 percent of electricity from renewable sources by 2025.

The ACC is among just a handful of partisan utility regulators, and four of the current five commissioners—including the two new members elected in January—are Republicans. Kevin Thompson, who for 17 years worked for the state’s largest gas utility, and Nick Myers are both outspoken critics of the clean energy mandate.

Shortly after the superior court judge sided with the ACC’s original decision blocking the plant expansion, the reconstituted commission allowed SRP to remake its case and voted unanimously to restart discussions with the power company.

Since then, the SRP has provided Randolph residents with a list of possible community investments and concessions should the expansion be approved.

“This is a classic case of systemic racism, one of many communities across the country where companies with money and power will go to any extreme to get what they want,” said Constance Jackson, the NAACP’s Pinal County branch president. “It’s sad the community has to go through this again because the decision was made. It should not be back on the ACC agenda.”

JP Martin, an ACC spokesperson, said: “There is a drastic misunderstanding that the SRP extension in Coolidge is on any agenda. The commission’s legal division is engaging with SRP’s legal team—that is all that is currently known.”

A utility spokesperson said: “SRP continues to believe that the ACC’s line siting committee, which heard all the testimony, toured the plant and toured the Randolph community, was correct when it approved the proposed expansion … The Coolidge expansion project would be required to comply with an air quality permit that restricts the emissions from the plant to levels that are protective of human health and the environment. The project also aligns with our commitment to clean energy and the transformation of the grid.

“SRP continues to seek a collaborative solution with the Randolph community that would provide a way forward and we are committed to continuing to grow our relationship and partnership with the community.”

In Randolph, residents are weary but not defeated. “I know it doesn’t look like it now, but Randolph was a great place to grow up. This is our history and we are the voices of our ancestors, so this place is priceless to me,” said Kyle Muldrow, 53, an army veteran and fourth generation resident. “The ACC made its decision, this should be over.”