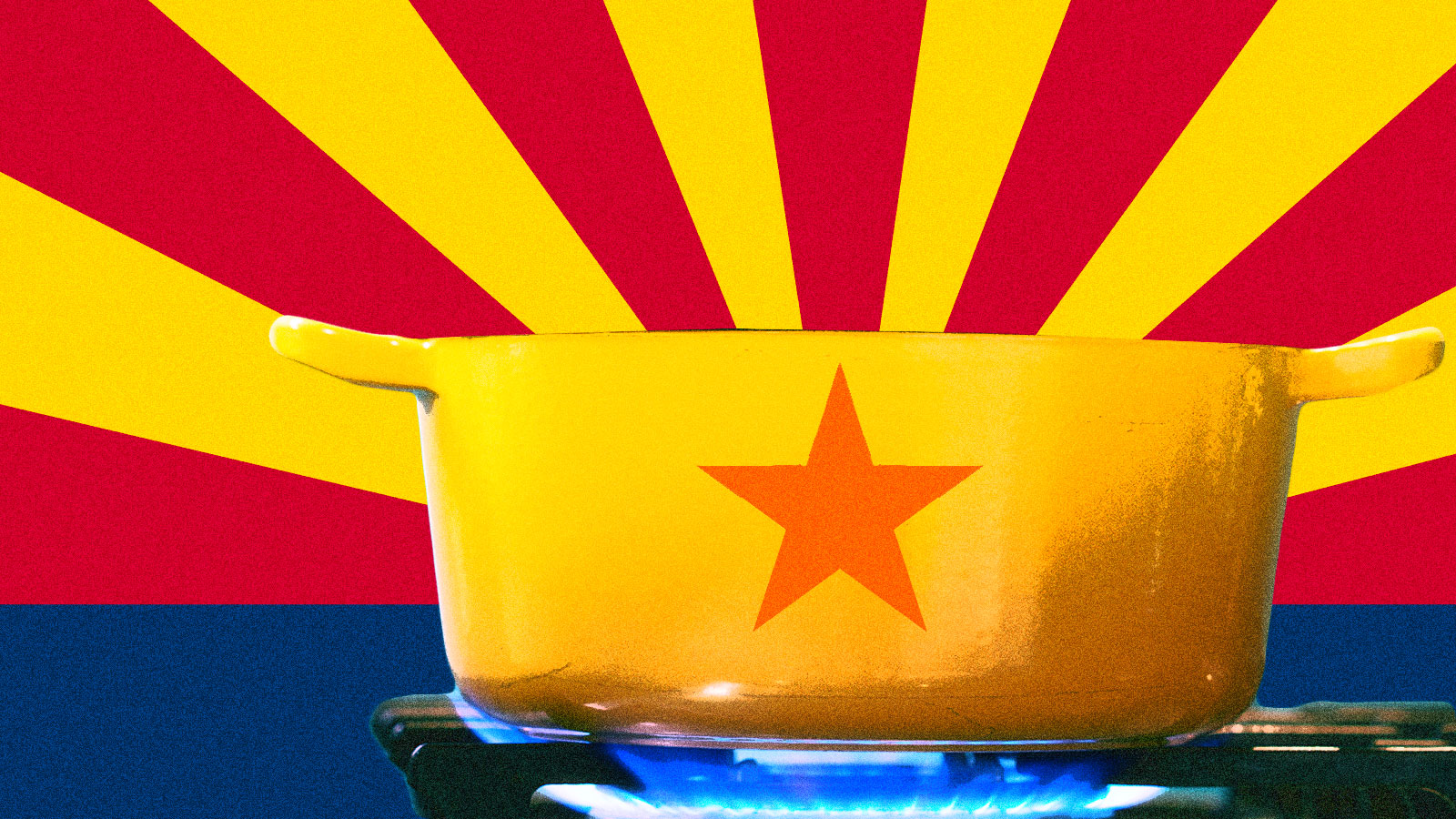

Like many cities around the country, Phoenix, Arizona, has a plan to achieve an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. But a new state law that was fast-tracked through the Arizona legislature and signed by the governor last week could cripple Phoenix and other Arizona cities’ ability to pull their climate plans off.

It only took a month for HB 2686 to go from bill to law after it was introduced on January 21. The new law prevents Arizona’s cities and towns from passing codes or ordinances that could “have the effect of restricting a person’s or entity’s ability to use the services of a utility provider.” In essence, it prohibits them from banning natural gas or other fossil fuels in buildings.

The funny thing is that there’s no evidence that anyone in the state was even considering a gas ban. “No cities, that we are aware of, were even remotely looking at or considering this type of action,” Caryn Potter, the Arizona program associate for the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, or SWEEP, told Grist.

Potter said the bill was indicative of the legislature’s fear of the “Berkeley-ization” of Arizona. While it’s true that Californians have been flocking to neighboring states in search of lower taxes and costs of living, Potter said there’s no evidence of a sea change sweeping Arizona around the politics of natural gas. “They have this idea that they have to put the cart before the horse, when the horse is not even there,” she said.

That may be the case, but gas bans are, in fact, on the rise all over the country after Berkeley made the first move by banning gas hookups in new buildings last summer. Now more than 20 cities and counties in California have passed ordinances that strongly encourage electric appliances in new buildings, if not mandate them. In Massachusetts, the town of Brookline voted to ban natural gas in new construction in November — approval by the state attorney general’s office is still pending. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced that he wants to pursue a ban on oil and gas in buildings, but such a measure would have to pass the city council first. There are more bans under discussion in Maryland and Washington state.

The rationale behind all of these local anti-gas policies is, of course, to prevent catastrophic climate change. Proponents of gas bans cite the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which says that global emissions must fall dramatically in the next 10 years, and reach net-zero by 2050, to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees C. The fuels combusted in buildings for space heating, hot water, and cooking are responsible for 10 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. When utilities extend gas mains to new buildings, that infrastructure is expected (and financed) to last upwards of 50 years, meaning it will be around, and will potentially still be siphoning dollars, long after cities expect to wean themselves off of their reliance on gas.

Potter said that constructing fully electric buildings in Arizona is cheaper than hooking up new buildings to gas lines. The real issue, she said, is creating incentives to retrofit older buildings that use gas. SWEEP, a nonprofit that aims to advance energy efficiency and clean transportation policies and programs throughout the Southwest, calculated for Grist that the greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of natural gas in Arizona’s buildings produced 3.7 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2018, approximately the same amount as the state’s 1000-megawatt coal-fired Cholla power plant.

The American Gas Association (AGA) has criticized building gas bans for taking away customer choice and argued that they won’t deliver the intended results. “The idea that denying access to natural gas in new homes is necessary to meet emissions reduction goals is false,” association’s president and CEO Karen Harbert said in a statement last year. “In fact, denying access to natural gas could make meeting emissions goals harder to achieve and more expensive.” The AGA released a report in 2018 which found that the cost of electrifying buildings is higher than other emissions reduction options, but other groups have criticized the assumptions underpinning its conclusions.

Potter said the new bill in Arizona moved so quickly that SWEEP barely had a chance to react to it or talk to legislators about its implications. The Energy and Policy Institute reported that Southwest Gas, a utility that serves more than 2 million customers in Arizona and a member of the AGA, donated thousands of dollars to the campaigns of Arizona Senate President Karen Fann and Speaker of the House Rusty Bowers in December, just weeks before those legislators introduced the preemption bill. The AGA has also launched a national campaign to mobilize communities against gas bans.

While Potter sees the preemptive legislation as a setback for Arizona, she said that cities like Phoenix have other tools to reduce emissions from buildings and encourage electrification. For example, Arizona law still allows municipalities to adopt stricter building codes than the state codes, so cities could require that buildings only use appliances that meet certain efficiency standards.

“I don’t think it will prevent cities from reaching their targets, but it may make it more difficult to do so,” Potter said.