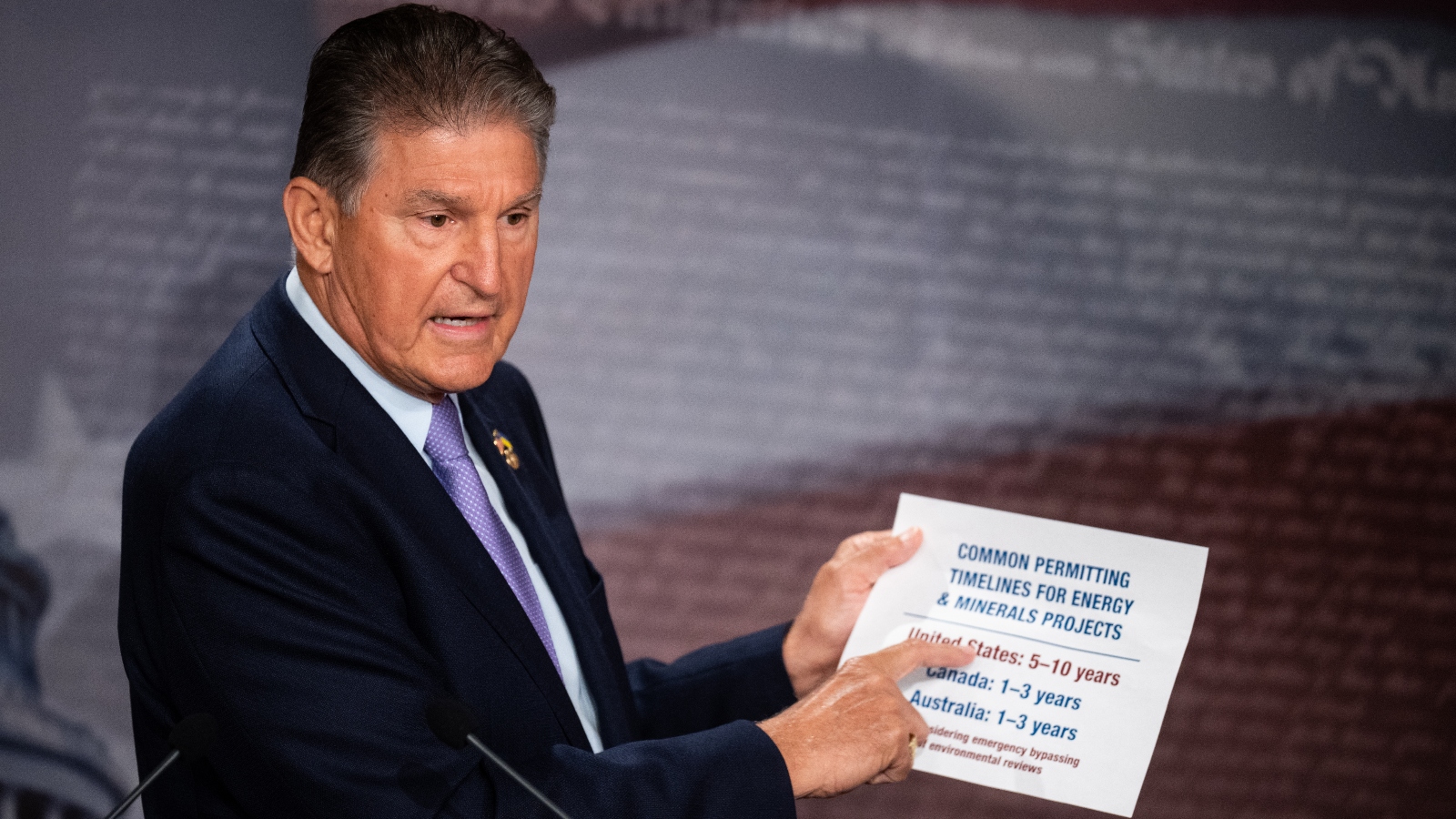

Joe Manchin on Wednesday made public the text of his long-awaited permitting bill, the result of a side deal that the senator from West Virginia made with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer as a condition of passing major climate legislation last month. The bill provoked a variety of strong and polarized reactions from climate experts, environmental justice advocates, and renewable energy boosters, but it’s still unclear how it would change the nation’s energy mix. Even less certain is whether the legislation can pass as a rider to a budget resolution that Congress must pass by the end of the month to avoid a government shutdown.

The bulk of the bill consists of a series of revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, a sweeping 1970 law that requires federal agencies to review the environmental impacts of nearly all the decisions they make. The legislation would set a two-year ceiling on NEPA reviews of major infrastructure projects and a one-year ceiling on reviews of minor projects, though it isn’t clear what would happen if agencies exceed those timelines, and the bill doesn’t contain any funding to help agencies meet the new mandates. The bill also shrinks the statute of limitations on court challenges against agency permitting decisions from six years to about five months.

In theory, the reforms in the bill will make it easier to build all kinds of energy projects, from mines to pipelines to gas terminals to solar farms. In practice, it’s unclear how big of an effect the bill will have on construction timelines, or how it will benefit fossil fuel projects compared to renewables.

Many liberal and libertarian thinkers have criticized NEPA and expressed support for the bill, saying it would speed up clean energy. The free-market R Street Institute, for instance, has found 40 percent of the active NEPA reviews at the Department of Energy are for clean energy projects, compared to 15 percent for fossil fuels. The liberal columnist Ezra Klein, writing for the New York Times, said that the bedrock environmental law is one of many “checks on development that have done a lot of good over the years but are doing a lot of harm now.”

However, some research has suggested that NEPA review delays are primarily caused not by the constraints of the law itself but by staffing shortages at the administrative agencies charged with undertaking the reviews. The Southern Methodist University law professor James Coleman, furthermore, has written that NEPA reform wouldn’t do much to help renewables, since the main obstacle for those projects tends to be getting approval at the state and local level, where they often run into fierce opposition.

Many of the bill’s opponents also allege that the bill further burdens communities vulnerable to the harms of polluting infrastructure by weakening the review process for new projects and closing off avenues for litigation. Representatives from Greenpeace, the Sunrise Movement, the Indigenous Environmental Network, and dozens of other environmental groups all spoke out against the bill after hosting a rally outside of the U.S. Capitol earlier this month to oppose Manchin’s deal with Schumer.

“By making it more difficult for communities to participate in the permitting process, the fossil fuel industry and others will be able to hastily secure permits without adequate time for review and consideration of the environmental impacts, which will only continue the legacy of pollution that has turned these communities into sacrifice zones,” said Peggy Shepard, co-founder of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, a Harlem-based advocacy organization, in a statement.

Reception inside the Capitol was no friendlier. Schumer and Manchin plan to attach the bill to a so-called continuing resolution, a measure that temporarily funds government operations, forcing senators to vote on keeping the government open rather than approve or deny the permitting deal on a standalone basis. A number of progressive senators, including Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, said they wouldn’t support a funding resolution with the permitting language in it, with Warren saying it “should be debated and voted on separately.” Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, meanwhile, called it a “disastrous side deal,” and a group of several dozen progressives in the House of Representatives have also come out against the deal. Many Senate Republicans, burned by Manchin’s support of the Inflation Reduction Act, have announced their opposition as well.

A continuing resolution needs 60 votes in order to pass the Senate, so Manchin would need to garner support from at least 10 Republicans even if the entire Democratic caucus supported the bill. Given the number of early defections on both sides, it seems unlikely the bill will find that many supporters outright. What’s less clear is whether all the senators who have announced their opposition would be willing to sink a high-stakes funding bill over their opposition to permitting reform. If the continuing resolution doesn’t pass by September 30, the federal government will shut down, marking the first government shutdown of the Biden administration.

The bill’s other provisions are a mixed bag when it comes to climate. The law would require the Department of Energy to identify a list of 25 “critical energy projects” that will receive expedited consideration by federal agencies. In keeping with Manchin’s all-of-the-above energy philosophy, the list must contain at least five fossil-fuel projects, four mining projects, five renewable energy projects, and one carbon capture project. Only five of the 25 slots are left up to the Biden administration’s discretion.

A section about electrical transmission, meanwhile, garnered praise from supporters of renewable energy. The bill gives the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission expanded authority to promote the construction of new electrical transmission lines between regions of the country, and also allows the commission to allocate the costs of new lines to the electricity users who will benefit from them. That’s a complicated way of saying that the commission can incentivize utilities to build new lines by ensuring it makes financial sense for them to do so. A recent analysis from Princeton found that the United States will have to double the pace at which it installs transmission lines in order to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

“Senator Manchin’s bill includes provisions that will help streamline the transmission approval process, improving our ability to meet our nation’s decarbonization goals by better connecting our key renewable resources to our largest population centers,” said Gregory Wetstone, president and CEO of the American Council on Renewable Energy, a trade group representing renewable power companies.

Perhaps the most controversial provision, though, is the one that clears the path for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a 303-mile pipeline that would move natural gas from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia. The pipeline has been a key priority for Manchin and has faced sustained opposition from several community groups citing environmental, public health, and safety concerns. A number of lawsuits challenging the pipeline’s permits are pending in state and federal courts, and earlier this year, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals invalidated permits issued by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service.

Manchin’s bill instructs these agencies to re-issue opinions, permits, leases and other authorizations required to operate the pipeline and exempts those federal actions from judicial review. That means community groups would no longer be able to challenge the pipeline’s permits in court. Jared Margolis, an attorney with the environmental group Center for Biological Diversity, said that it’s not clear what the bill’s passage might mean for the pending lawsuits, but it could lead to the lawsuits being considered “moot” and dismissed.

Since Congress passed the nation’s environmental laws, it can dictate where they apply, Margolis said. A bill fast-tracking the controversial Keystone XL pipeline took a similar approach several years ago. If Manchin’s bill passed, Margolis said, it would set a dangerous precedent. “The fact that Congress is getting into project-level skirmishes is surprising and scary,” he said. “If the new thing is going to be getting congressional support, then it becomes about political support and public opinion instead of bedrock environmental laws.”

The pipeline provision caused at least one further defection on the Democratic side of the aisle. Senator Tim Kaine of Virginia, whose state would be the pipeline’s final destination, told reporters that the inclusion of the language made the bill “completely unacceptable.”

“I will do everything I can to oppose it,” he said.