It was the beginning of 2009, and the U.S. economy was hemorrhaging more than half a million jobs every month. The housing bubble had burst and set off the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. In February, a few weeks after being sworn in, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, an $800-billion stimulus package designed to reinvigorate the economy and save millions from losing their houses and jobs.

Hidden in the Recovery Act was something that largely escaped notice at the time — $90 billion earmarked for clean energy generation, electric vehicles, transit, and training for green jobs. By many accounts, that 10 percent chunk of the stimulus bill changed the trajectory of renewables in America. Now, 12 years later, with 36 million Americans out of work amid the economic fallout from the coronavirus, it could also serve as a model for stimulus measures to come.

Joel Jaeger, research associate at the World Resources Institute, said that countries around the world already look to the Recovery Act for examples of how to boost their economies and renewables at the same time. “The U.S. was really the only country that invested a ton in renewable energy and building efficiency,” Jaeger said. “It did more than any other country in the world.”

In 2008, wind and solar energy were just blips on the U.S. electricity grid: Solar energy produced 0.1 percent of the country’s power; wind less than 1 percent. Renewables were on the rise, but their contribution to the electricity grid remained vanishingly small — almost half came from coal.

That was all about to change. Months before the 2008 election, a group of energy experts, led by Carol Browner, the former head of the Environmental Protection Agency and Obama’s top energy and climate advisor, began hammering out the details of a spending proposal that could boost the economy and also tackle some of the incoming administration’s climate goals.

“We had to focus on long-term stability of the economy,” Browner explained. “And then within that we were looking at initiatives that were built for the long-term, in the context of energy and improving and protecting our health and environment.”

In November, Democrats won control of both houses of Congress. They soon sent a stimulus package to Obama that provided over $25 billion to renewable energy generation, $20 billion to energy efficiency programs, $18 billion to transit programs, and $10 billion to modernizing the country’s electricity grid, among other miscellaneous projects.

And although the Recovery Act was frequently mocked — Republicans labeled it the “failed stimulus” — its effect on renewable power was undeniable. Today, solar and wind provide 9 percent of the country’s electricity, while coal has fallen to 23 percent. In the decade following the Recovery Act, wind generation quintupled, and solar generation multiplied by a factor of 48.

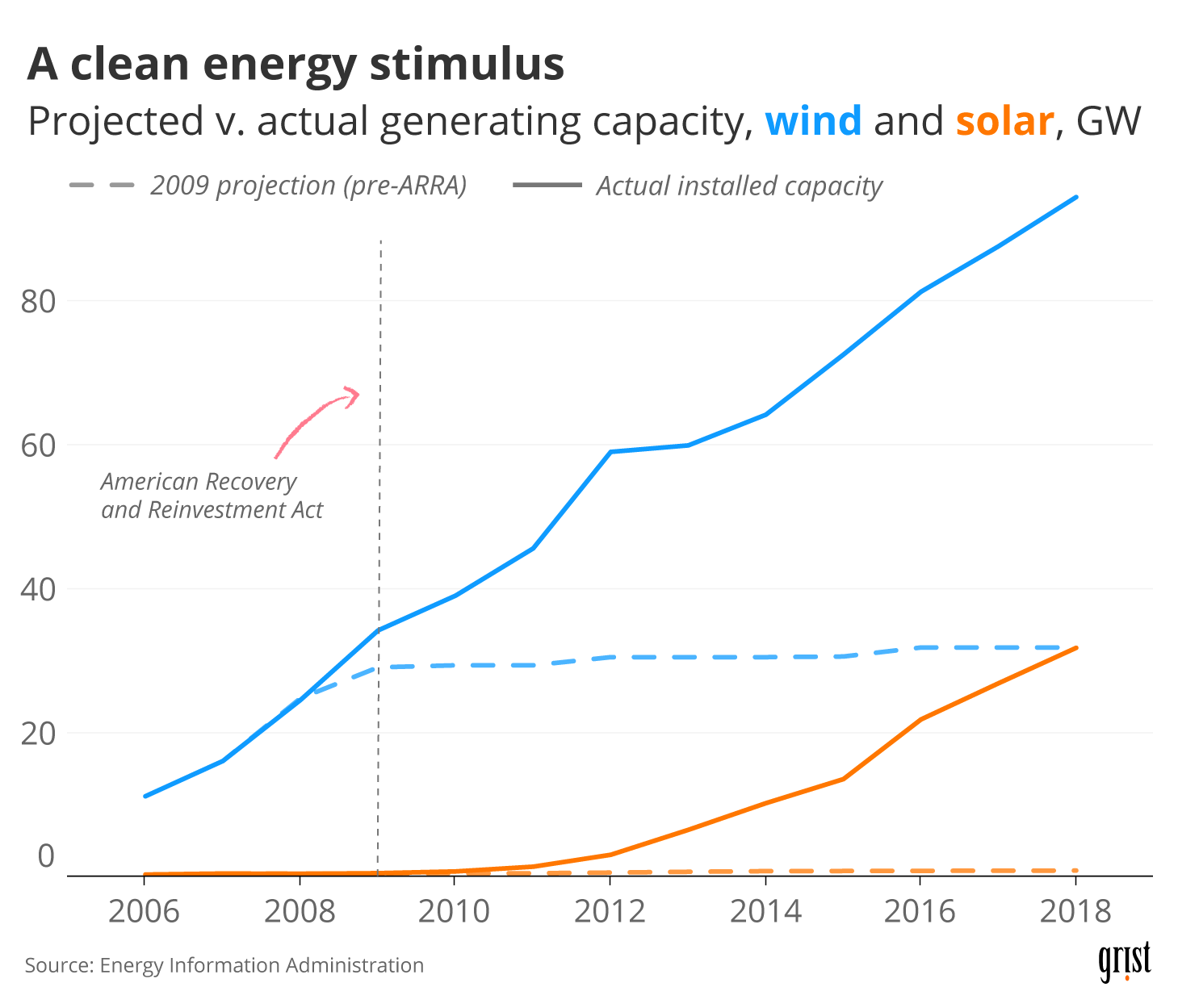

Joseph Aldy, the sole economist on Obama’s energy and environment transition team who’s now a professor of public policy at Harvard University, said that one way to see the enormous success of the Recovery Act was to compare the U.S. Energy Information Agency’s pre-2009 predictions for wind power’s growth with reality.

“We blew it away,” he said. “And when I mean blew it away, I mean that by 2011, we were up to what the EIA forecast we would have installed by 2030. The world in which we had 80 gigawatts of wind by 2020? No one envisioned that.”

Clayton Aldern / Grist

So how did they do it? $90 billion, for starters. The federal government had never spent so much money to support clean energy. But it wasn’t simply the direct boost from stimulus spending.

Browner said that one of the most innovative parts of the Recovery Act was a move to turn tax credits into cash for energy developers. Then and now, federal tax credits help cover the cost of many renewable energy projects, even though most small energy companies don’t owe enough taxes to the government to take full advantage of them. Developers would typically sell the tax credit to big banks, for something like $0.90 on the dollar. “They would get the cash they needed, and somebody would get the tax credit,” she said.

The financial crisis upended everything, and markets of all kinds collapsed, taking banks down with them. “That tax credit market disappeared, like literally overnight,” Browner said. Some of the biggest players in the market were financial firms like American International Group, or AIG, the now-defunct Lehman Brothers, and others which either collapsed or teetered on the edge of bankruptcy.

So the Recovery Act did something unprecedented. Instead of the tax credit, the federal government offered developers cash for up to 30 percent of their project costs, unlocking a bottleneck at the heart of renewable projects and ultimately pouring $25 billion into green energy. Developers soon started building new solar plants and wind farms again.

Workers finish installing solar panels funded by federal stimulus funds atop a government building in Lakewood, Colorado in 2010. John Moore / Getty Images

“That was a real turning point,” said Kevin Lynch, managing director of external affairs at Avangrid Renewables in Portland, Oregon. “I think we about doubled our generating capacity in the U.S. as a result of that.” Avangrid, at the time called Iberdrola Renewables, built 28 projects that benefited from the grants — ones that Lynch expects will continue to provide jobs and tax revenue for decades.

The Recovery Act also funneled money into programs meant to stimulate new clean energy science and technology. $400 million was earmarked to launch the Advanced Research Projects Agency for energy, or ARPA-E, a kind of scientific incubator for new green technologies. (Trump has repeatedly threatened to defund it).

The Department of Energy also doled out about $4.6 billion in guaranteed loans to companies investing in new wind, solar, and geothermal energy technologies. But that program came at a political cost: One of those companies was Solyndra, the maker of cylindrical solar panels that ultimately defaulted on its $535 million government loan and became a Republican byword for everything wrong with the stimulus.

“There was political hay to be made with Solyndra,” Aldy said. But he thinks the scandal overshadowed what was actually a success; the point of the program was to take risks on technologies that could have big payoffs (and big risks). The program doled out money to many projects that succeeded, including the 300-megawatt Agua Caliente solar facility in Arizona and the 99-megawatt Granite Reliable wind farm in New Hampshire.

By the end of Obama’s presidency, the Department of Energy’s loan guarantee program had taken in $30 million more in interest payments than it had lost from defaults.“I wish we had more Solyndras,” Aldy said. “To me, the fundamental problem with the loan guarantee program is that we didn’t take enough risk.”

Now, as the economy sinks under the weight of the coronavirus crisis, experts are looking to the Recovery Act for how to move forward. In the past two months alone, clean energy lost 600,000 jobs — and more cuts are likely on the way. Many renewable energy companies will need help to survive.

Today, environmentalists and policymakers are pointing to new ways that stimulus plans can bolster the economy and save the planet at the same time. Some have suggested a green jobs corps; others have put their money on an overhaul of the transportation system that focuses on walking, biking, and transit instead of new highways. A new report commissioned by the Sierra Club proposes that lawmakers spend $320 billion on a combination of clean energy, energy efficiency, and land restoration.

Some policies from the Recovery Act — like the federal loan guarantees — probably won’t make the cut. Nobody wants to be blamed for another Solyndra. “At the end of the day, it was sort of a lost opportunity that also created a lot of political baggage,” said Aldy. “I think we have to avoid programs like that in the future.”

But others, like turning tax credits into cash, could prove useful again. The tax credit provision was “probably the single most important piece of that 2009 Recovery Act that we’d like to see come back — and that we really need right now to help get workers back on the job,” said Gregory Wetstone, president of the American Council on Renewable Energy. Wetstone said that reviving that Recovery Act policy could help energy companies deal with the reality that, as the economy slumps, the tax credit market that funds their projects also shuts down.

There’s also a question of new goals. In 2009, according to Aldy, the Obama administration’s focus was mostly on cutting carbon emissions as much as possible to try to prevent dangerous climate change. But extreme weather and sea-level rise are being felt now. Aldy said that any administration that cares about climate change will have to consider moving money toward the construction and maintenance of climate-resilient infrastructure, like improved drainage systems and sea walls.

Moreover, while some states have seen rapid growth in renewables since the last financial crisis, others have lagged behind. Over the past decade, many states passed or updated laws requiring electric utilities to get a certain portion of their energy from renewable sources, providing yet another incentive for clean energy that complemented the Recovery Act investments. Aldy said that the federal government could help, say, West Virginia and Wyoming, turn to more wind and solar with the help of targeted spending and tax credits.

It’s hard to imagine any of this legislation getting passed without a new occupant of the White House and a Senate taken over by Democrats. In the decade since passing the Recovery Act, Congress has shown little interest in supporting clean energy — nothing like the $90 billion invested under the Recovery Act. The massive $2 trillion rescue package passed by Congress in March didn’t include any climate-friendly provisions; in fact, some media outlets have reported that fossil fuel companies have recently received millions of dollars in loans intended for small businesses.

The bill President Obama signed back in February 2009 still stands out as an example of what could be possible — the first green stimulus of its kind. Browner said that it’s hard to imagine where the clean energy industry would be today without the government’s help. “I’m not sure that renewables would have made it,” she said.