From where Joe Rand stands, there’s good news and there’s bad news about renewable energy development in the United States — and it’s hard to tell which is more significant.

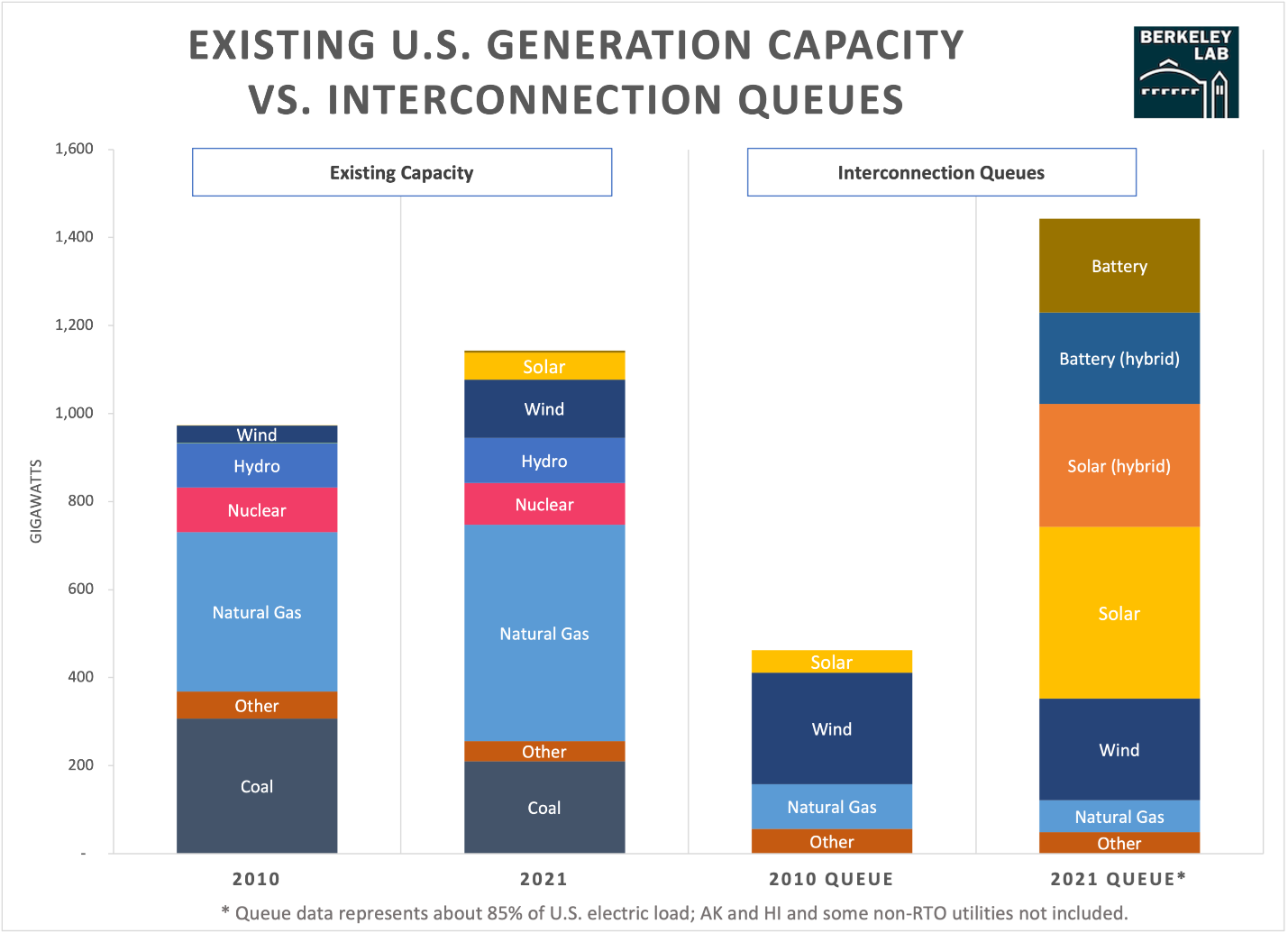

Rand is a senior scientific engineering associate at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where he studies almost every facet of renewable energy, from policy and costs to public acceptance and other barriers to deployment. Last week, Rand and his colleagues put out a new analysis finding that as of the end of last year, 93 percent of all proposed utility-scale electricity projects that had applied to connect to the grid were wind farms, solar farms, or batteries — which can store energy from renewables and dispatch it when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

That’s the good news. But submitting an application with the organization that oversees a region’s grid — commonly known as a regional transmission organization or a grid operator — is just the first step. Next, developers have to conduct several studies and reach an “interconnection agreement” with the grid operator. They also have to obtain construction permits and negotiate deals with power buyers and communities. And then, of course, they have to actually build the project.

This entire period between initial application to the grid and having a functioning utility-scale power plant is called the “interconnection queue,” and right now, it’s jammed up like rush hour traffic. The study found that as of 2021, the average power project was spending 4 years on the queue, compared to just 2.1 years in the decade leading up to 2010. The number of projects withdrawing from the whole process each year seems to be going up, too.

“How cool is it that we have all this clean capacity in the queue? It’s mind blowing,” said Rand. “But this same study shows all these inefficiencies, backlogs, and barriers.”

The number of applications is, indeed, mind blowing. If all of the proposed projects that were sitting in the queue at the end of 2021 were built tomorrow, the U.S. would hit Biden’s goal of an 80 percent clean electric grid eight years early, according to the Department of Energy. It’s not just that renewable energy applications have increased relative to fossil fuels. The total amount of electricity capacity tied up in the queue is about three times higher now than it was a decade ago.

That’s important, because tackling climate change doesn’t just require replacing fossil fuels with renewables — we also need to generate a lot more power. Switching to electric vehicles and swapping out gas-fueled home appliances for electric heaters and stoves could increase U.S. demand for electricity by 40 percent by 2050.

But the lagging interconnection process is slowing down the energy transition, Rand said.

The primary reason for the backlog is the increasing volume of projects entering the queue. Once a proposal for a solar farm is submitted to the queue, for example, it has to undergo a series of studies to determine which upgrades would need to be made to the transmission system before it can be connected. Then the developer has to reach an agreement with the regional transmission organization about who will cover the upgrade costs. But the staff at those organizations have limited capacity to do all that paperwork and analysis.

Will Bliss, the director of engineering at a small solar farm company called East Light Partners that develops projects in New York state, said that it used to take his firm two years to get a proposal through the bulk of the process. Now it has a project that was submitted to the grid operator in 2020 and is only halfway through the process. He said the delays increase uncertainty for all the other partners on a project, like the people who own the land the solar farm will be built on and whoever has agreed to ultimately buy the power, which increases costs.

Bliss attributed the delay to the New York grid operator being understaffed and having an application process that was designed for large industrial power plants, not lots of small solar farms. “I do understand how challenging their job is,” he said. “The systems just weren’t designed for tens of hundreds of applications to get submitted within a calendar year.”

Rob Gramlich, the executive director of Grid Strategies, a consulting firm that focuses on integrating clean energy into the electric grid, said that the “process problem” goes beyond the large volume of small renewable projects applying for connection Many transmission organizations study one project at a time on a first-come-first-serve basis, and every subsequent study assumes that the projects that came before it will get built.

“Very often those projects will get assigned costs for upgrades, and then decide to terminate their project,” Gramlich said. “Then every project behind them has to be restudied, so we have a never-ending process of restudy.”

The bipartisan infrastructure bill that President Joe Biden signed last year contained a few provisions to facilitate the construction of new transmission infrastructure, which would help alleviate the problem. But Gramlich said that more proactive planning from regional grid operators is also needed. He said that ERCOT, the transmission organization in Texas, plans grid upgrades for expected future generation, which helps make the interconnection process there relatively cheap and easy. Another grid operator, PJM Interconnection, which oversees the grid in several mid-Atlantic states, is shutting down its queue altogether in order to develop a new, more efficient approval process.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the agency that oversees transmission planning in most of the U.S., is also working on reforms, and will be taking the issue up at its monthly meeting this week. It will also look at finding a more equitable way to spread the costs of transmission upgrades so that renewable energy generators aren’t asked to shoulder costs that benefit all grid users, like utilities and other power generators.

“It ends up being, very often, a disproportionate charge on the generators,” said Gramlich. “And that’s serving as a barrier to entry for clean, renewable sources. So getting to a more fair system where all the beneficiaries pay for transmission that gets built would alleviate that barrier.”

The backlog of applications isn’t the only problem holding renewable power back. Rand’s study found that the average amount of time between initial application and interconnection agreement is going up, but so is the amount of time it takes to get from an interconnection agreement to an operational power plant. Rand attributed the finding in part to increased community opposition to renewable energy projects, but said another challenge was finding a buyer — like a local government, utility, or private company — for the power. Although many buyers are eager to purchase renewable energy, market conditions vary considerably from place to place.

“You might have a project enter the queue and even work all the way through the queue and get a signed interconnection agreement but still not have an offtaker for the power,” he said.