On a recent Saturday, Monaeka Flores made the drive from her apartment to her family’s land on the north coast of Guam, the U.S. island territory about 1,500 miles south of Japan. As she steered through a gap in a limestone cliff, the land fell away to her right. A lush tropical forest sloped down to a white sand beach scattered with dark, porous rocks. Beyond that, Flores could see a fringe of reef and the bright blue of the western Pacific stretching to the horizon. Driving north to Inapsan Beach, toward her family’s land, she always feels “this excitement, this energy, this joy bubbling up inside me,” she said.

Inapsan Beach is where Flores learned how to swim. It’s where she first donned snorkeling gear to gaze, wide-eyed, at the tropical fish that dart around the reef. It’s where her family camped, unfolding cots beneath the tin-roofed pavilion that her grandfather, father, and uncles built. Today, it’s where her extended family still gathers to fish, to barbecue, to play music and chat while her young nieces and nephews splash in the waves.

Inapsan is land that Flores’ family ranched on for generations. They are CHamoru, Indigenous people who have called Guam and the other Mariana Islands home for more than 3,500 years. “When I’m there, I feel the sadness and pain drain from my body,” she said. “It is such a beautiful place. Such a giving, healing place.”

Now, that place is threatened.

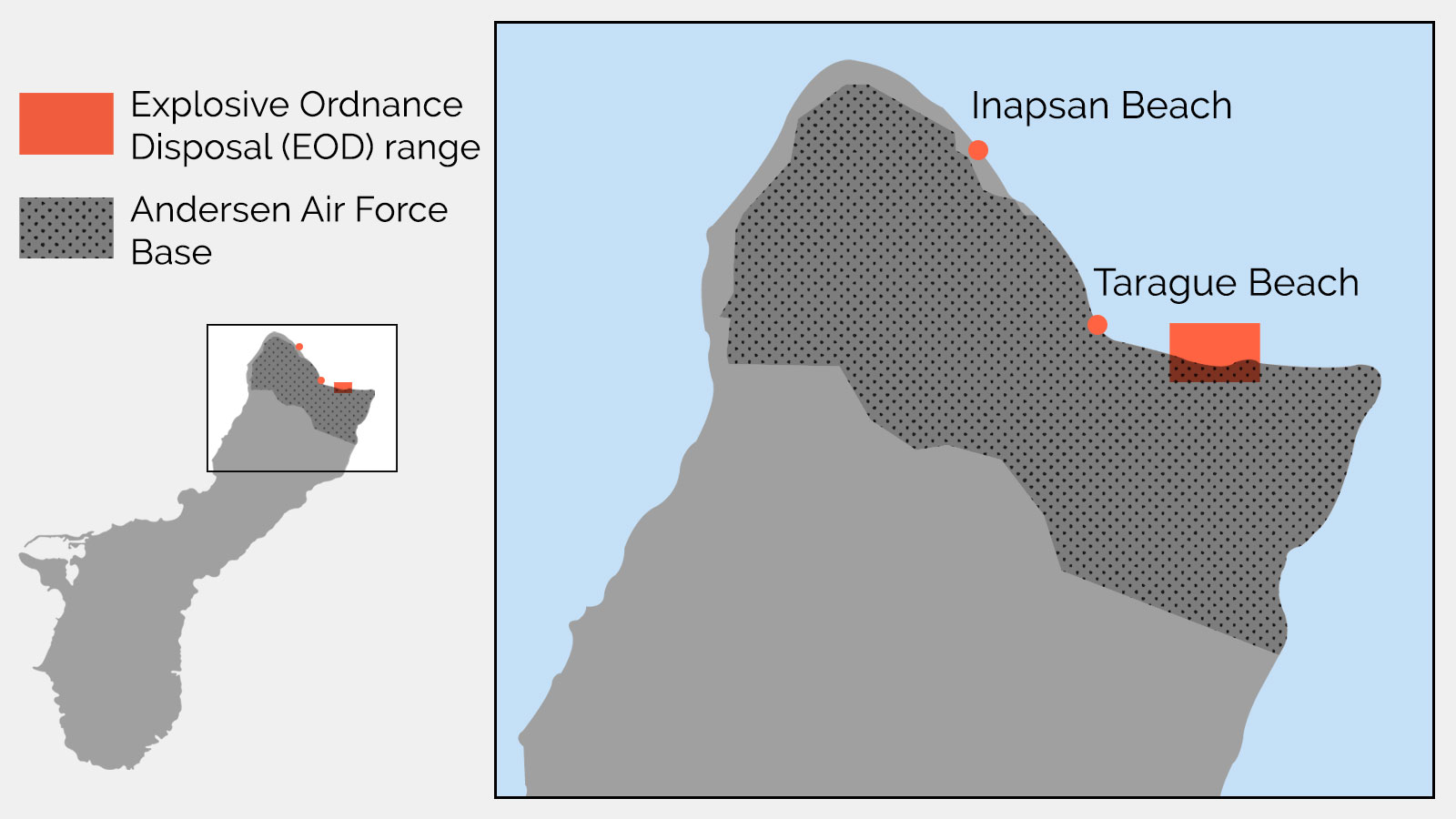

About three miles southeast of Inapsan, Andersen Air Force Base operates an explosive ordnance disposal range on Tarague Beach. In May last year, the Air Force applied to renew a permit to destroy up to 35,000 pounds of excess or obsolete munitions each year — everything from incendiary bombs to bullets, from anti-tank mines to smoke grenades — by detonating and burning them right on the beach.

If granted, the permit will give Andersen Air Force Base the option to conduct open burning and open detonation operations for the next three years, releasing a slew of toxic chemicals, including explosives like RDX, HMX, and TNT, thyroid-disrupting compounds like perchlorates, and persistent toxins like PCBs and PFAS. Black plumes could rise from the open burn pits. “Kickout” from the explosions could be flung up to half a mile away, contaminating the nearby reef and limestone forest. The chemicals could accumulate in the soil, leach down, and poison the shallow, freshwater aquifer that provides water for 80 percent of Guam.

To prevent this, in late January, a community group called “Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian” filed a lawsuit against the Air Force and the Department of Defense. (In CHamoru, prutehi means protect, and Litekyan is the CHamoru name for an ancient village in northern Guam, an area now known as Ritidian.) The group, which Flores helped found to protect natural and cultural resources on the island, says the military failed to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, when applying to renew the permit. They argue that Andersen Air Force Base did not consider the environmental and cultural harms that could be inflicted by detonating and burning hazardous waste in the open air.

A spokeswoman for Joint Region Marianas, which is responsible for environmental compliance for military bases on Guam and the surrounding islands, declined to comment on the pending lawsuit, but wrote: “The Department of Defense works with our Government of Guam partners to ensure we adhere to all required environmental regulations.”

“At the end of the day, the Air Force is not above the law,” said David Henkin, an Earthjustice attorney representing Flores’ group. “They’re supposed to be protecting us from threats, not creating threats.”

Open burning and open detonation operations consist of destroying waste munitions by pouring diesel on top of them and lighting them on fire or by blowing them up — crude disposal methods that release contamination directly into the environment.

In 1978, the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, proposed banning the open burning of all hazardous wastes, including explosives. The Department of Defense and some companies objected, arguing that there was no safe alternative for dealing with certain types of materials. When the EPA finalized the regulation in 1980, the agency made an exception for explosive hazardous wastes that could not be “safely be disposed of through other modes of treatment” — an exception that was only supposed to be a stopgap until safer technology could be developed.

Much has changed in the past 40 years. A recent report commissioned by the Department of Defense found that there are now viable alternatives for treating “almost all” conventional munitions. Some can be disassembled and the explosive material can be burned or detonated inside furnaces or kilns, some can be treated within special detonation chambers, and some can be chemically neutralized.

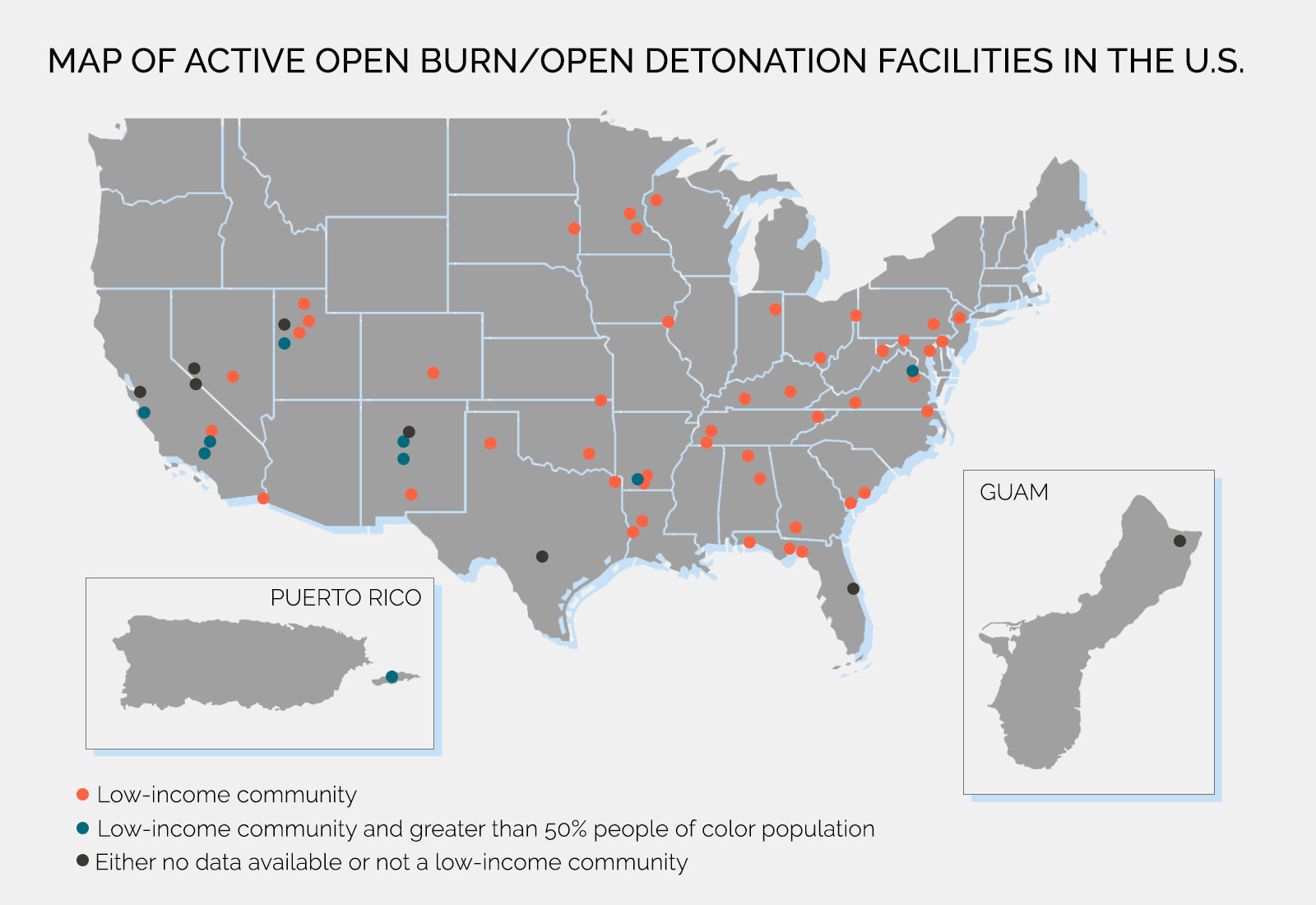

In the mid-1980s, about 80 percent of the waste munitions that the Department of Defense destroyed were handled at open burning or open detonation sites. In recent years, that fraction has fallen to about 30 percent. Still, there are currently 67 open burning and open detonation facilities operating within the U.S. and its territories. Some are run by private industry and other government agencies, but the majority, 38, are run by the military. These sites destroy excess, obsolete, or unserviceable munitions, including bullets, projectiles, mines, fuzes, and missiles, as well as bulk propellants used to manufacture ammunition, bombs, and explosives. During fiscal years 2016 and 2017, the Department of Defense destroyed more than 44,000 tons of munitions via open burning and open detonation.

In 2021, the EPA began working on rule-making to consider requiring owners and operators of open burning and open detonation facilities to evaluate and implement alternative methods of treating waste munitions. The agency began holding meetings with stakeholders last month and anticipates publishing a proposed rule in late 2022 or early 2023. Frontline communities are skeptical about whether the new rule will address the root cause of the problem.

In the meantime, these sites continue to wreak havoc on communities across the country, as detailed in an investigative series published by ProPublica in 2017. More recently, a new Earthjustice analysis revealed that 88 percent of open burning and open detonation sites are in low-income communities, and many are in communities of color.

“These are our ‘domestic burn pits,’” said Laura Olah, co-founder of the Cease Fire Campaign — a coalition of more than 70 groups against open burning and open detonation of waste munitions. “They are here, at home, in the United States and its territories, and almost exclusively in communities that are the most vulnerable to harm,” she said.

Flores and other members of Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian first heard about the Air Force’s permit renewal application in October last year when Guam Senator Sabina Perez held an informational hearing on Zoom. Perez explained that the Air Force’s explosive ordnance disposal range on Tarague Beach had been in use since 1980, and permitted by the Guam EPA since 1982. Open detonation operations had been taking place for decades, but open burning operations had been paused in 2002. Now, the Air Force was seeking to continue open detonations and to potentially resume open burning.

Representatives from the Guam EPA were present at the informational hearing. To Flores, the way they discussed the three-year permit renewal, “it almost felt like it was just going to be rubber-stamped,” she said.

The Guam EPA has not yet made a decision on the permit renewal application and is currently consulting with EPA Region 9. “This is at the discretion of the Guam EPA administrator, and he is taking into account every consideration before he issues his notice of decision,” said Nic Rupley Lee, public information officer for the Guam EPA.

After the hearing, Flores was frustrated. She was concerned that open burning and open detonation operations would pollute the island’s drinking water. Tarague Beach sits above Guam’s sole source aquifer: a fragile pool of fresh water that floats atop denser salt water within the island’s permeable limestone. In response to questions from Grist, an EPA spokeswoman wrote that “certain contaminants [from open burning and open detonation] pose more risk than others because they are highly soluble in water, and relatively stable and mobile in soil or surface water and groundwater … Ideally, OB/OD [open burning/open detonation] operations treating explosive wastes containing these constituents would not be located on a shallow aquifer.”

But some of the 104 different types of waste munitions that the Air Force listed in its permit renewal application, which it is seeking permission to burn or detonate above a shallow aquifer, do contain water-soluble contaminants, like PFAS. “These are chemicals that will never break down in our environment, that will continue to poison the land and the water for many generations to come,” Flores warned.

If approved, the permit would also allow the Air Force to burn and detonate materials not specifically listed in the application. In the past, the military has used the site to dispose of unexploded ordnance found around the island that dates back to World War II.

Flores was also concerned that the smoky air that blew away from the burn pits would be unsafe to breathe. That the fish her family and friends caught by spearfishing along the reef or from boats in the open water would be unsafe to eat. That CHamoru people would be unable to cultivate and gather traditional medicines near the range. And that green sea turtles, an endangered species, would be unable to nest on the beach where the blasts occur.

Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian says that the Air Force and Department of Defense never completed the requisite environmental review to address these concerns and consider alternatives.

Henkin says that the group wants to ensure that the Air Force complies with NEPA by making an informed decision and keeping the public apprised of the process so that they can provide input. “People need to know that things aren’t happening behind closed doors that are going to harm their environment,” he said.

In Flores’ view, “they decided that they didn’t need to do the work,” she said. “That’s why we’re taking them to court.”

To Flores, the Air Force’s plan for Tarague Beach is one more hazard on a long list of threats that CHamorus have faced throughout 500 years of colonialism. This threat, however, is especially personal. Part of Tarague Beach once belonged to Flores’ great grandfather.

In the 16th century, Spanish colonizers came to Guam, inflicting genocide through war and disease and reducing the CHamoru population by 90 percent. In 1898, the U.S. took control of the island as a result of the Spanish-American War. Then, on December 8, 1941 — the same day that Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor on the other side of the International Date Line — the Japanese Imperial Army invaded Guam.

Flores’ grandfather, Damian Castro Flores, who passed away nearly 20 years ago, remembered the day well. He told Flores that, for a few peaceful weeks, his family hid near Tarague Beach. They had a ranch there, where his father raised pigs and had planted hundreds of coconut trees to produce copra (dried sections of coconut meat that yield coconut oil). “They thought they might be safe there for a while,” Flores said.

When Japanese forces discovered the ranch, they took all of the pigs. They made Damian, 13 years old, work from sunrise to sunset processing the copra, and then they took that too. They also forced Flores’ great grandfather and grandfather, along with many CHamorus, to do hard, manual labor.

The U.S. returned to Guam in July of 1944 and retook the island in a grisly battle that went on for weeks. After World War II, the U.S. military gobbled up land. The government invoked eminent domain to seize CHamoru families’ properties, creating the military bases that span 30 percent of the island today.

“My great grandfather was really heartbroken to lose that land at Tarague Beach,” said Flores. It was where he had ranched, hunted, and fished throughout his life. He and Flores’ great grandmother began ranching in Inapsan, on a parcel of land just north of Tarague that belonged to her great grandmother’s family and still belongs to Flores’ family today.

Though they own the property in Inapsan, they can only access it by driving through Andersen Air Force Base. Each year, Flores has to apply for a pass to show an armed gate guard every time she drives north. “They’re our ‘hosts,’ and it’s a ‘privilege’ to be able to travel through the base,” said Flores. After 9/11, the installation locked down for months. Flores’ family was no longer raising livestock by then, but other families were, and many of their animals died. “It was horrible,” Flores said.

Flores hopes that one day, her family will be able to access their land in Inapsan freely, and that the government will return Tarague Beach. The land once owned by her great grandfather is currently split between the explosive ordnance disposal range and a recreational area for military families, equipped with volleyball nets and concrete picnic tables. Sitting below a hand-painted sign that reads “Land Back,” Flores said, “Every single family who’s lost land dreams about one day being able to return.”

Flores and her family won’t be able to return, though, if the land is too contaminated, or if unexploded ordnance remains. Henkin, the Earthjustice attorney, has seen it happen before in Hawaii. At an open burning and open detonation site on Oahu, the military failed to fully destroy anti-personnel bomblets. Now, the area is off-limits to everyone.

The federal government is legally required to “clean close” open burning and open detonation sites, meaning they must restore contamination levels to below what the government deems safe. But Flores has good reason to be skeptical that the government will meet these obligations. ProPublica’s investigation found that, at military hazardous waste sites across the country, “some of the most dangerous cleanup work that has been entrusted to contractors remains unfinished, or worse, has been falsely pronounced complete.”

The tab for cleaning up open burning and open detonation sites can run into the hundreds of millions of dollars — though it’s difficult to parse out exactly how much is attributable to open burning and open detonation and how much is due to other sources of contamination, like livefire ranges, that are often co-located.

Once certain pollutants reach the water table, no clean-up effort can remedy the damage. Olah, co-founder of the Cease Fire Campaign, lives in rural Wisconsin near the former Badger Army Ammunition Plant. Two open burning sites at the plant created toxic groundwater plumes. Olah’s group estimates that the federal government has spent over $250 million remediating the former plant. Still, DNT, which is used in the manufacturing of explosives and propellants, has been detected in groundwater monitoring wells at the site of the former plant at concentrations 25,000 times higher than what the state deems safe.

On the morning of January 24, 2022, Flores and several members of Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian stood outside the U.S. District Court of Guam, gazing up at the gleaming granite pillars. Flores felt a little intimidated as she walked into the federal building and slid her belongings through a metal detector. But when the court clerk stamped the complaint they were there to file, she felt tremendously proud. “We felt like our ancestors were there with us,” she said.

The Air Force and Department of Defense have until late March to respond to Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian’s complaint. Andersen Air Force Base can either withdraw its permit renewal application and conduct a new environmental review, or the case will be decided by the court, most likely this summer.

If Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian succeeds in preventing the Air Force from conducting open burning and open detonation operations on Tarague Beach, their work will not be done. In January 2021, in response to concerns expressed by the group, three United Nations Special Rapporteurs sent a letter to the U.S. regarding human and civil rights violations against CHamorus. The letter called attention to the ways in which the United States’ military buildup in the Pacific, and specifically the construction of a massive new live-fire training range complex, threatens to contaminate the island’s drinking water, decimate its wildlife and biodiversity, and desecrate CHamoru’s sacred sites, including burial grounds.

“The desecration that’s taking place, the access that’s being lost, the contamination that’s happening, it’s all connected,” said Flores. “It feels relentless.”

When it all starts to feel like a little too much, Flores hops in her car and heads for the north coast. She passes through the familiar gap in the limestone cliff and follows the road down into the forest. Where the pavement turns into a dirt track leading to Inapsan Beach, she parks, steps out of the car, and takes a deep breath of fresh, salty air. She reaches out to touch the sign to the side of the road: “Private Property: DoD personnel, dependents, contractors and employees are not allowed beyond this point.” She smiles.

“There’s something about seeing that sign that just never gets old,” she said. “It’s a small reminder that we’re still here. And we are not leaving.”