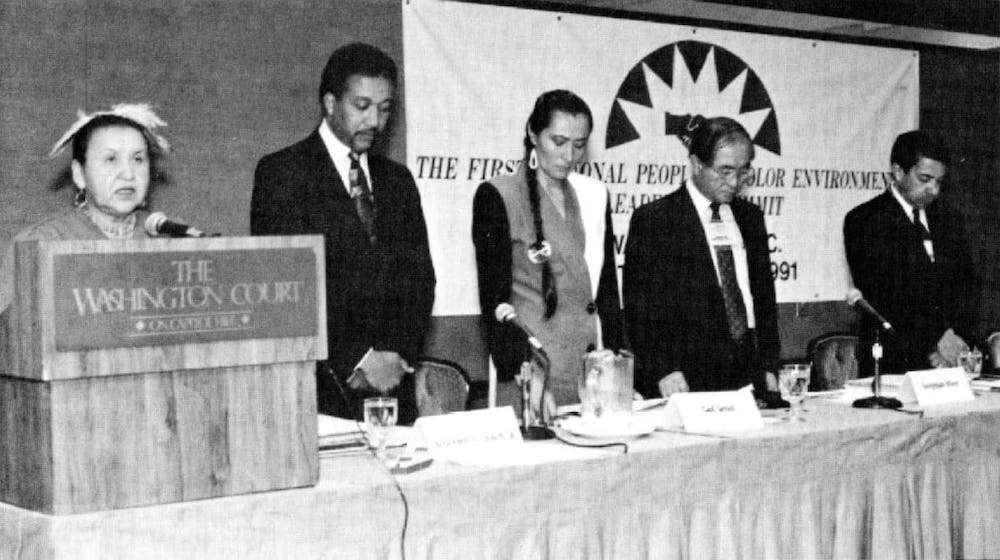

On October 24, 1991, nearly 300 Black, Native, Latino, Pacific Islander, Asian American, and other minority activists gathered in Washington, D.C. to discuss, for the first time in history, the environmental injustices their communities were experiencing. During the four-day event, delegates told stories of Black communities forced to relocate due to dangerously high pollution levels, farmworkers forced to live in homes built on abandoned chemical dump sites, Indigenous groups fighting against mining and nuclear testing on their reservations, and Asian immigrants developing respiratory problems after working for years in factories.

There was excitement, remembers sociologist Robert Bullard, an environmental justice advocate who served on the summit’s planning committee, but also anxiety. Conversations got heated. “We had to unpack, and throw off that baggage of mistrust that’s kept African Americans from knowing that much about Latinos, Latinos from Asian and Pacific Islanders and Indigenous people,” said Bullard. “Those first few days were very intense.”

“That was the moment that we came together — not knowing much about each other — but we learned during those first few days,” he added.

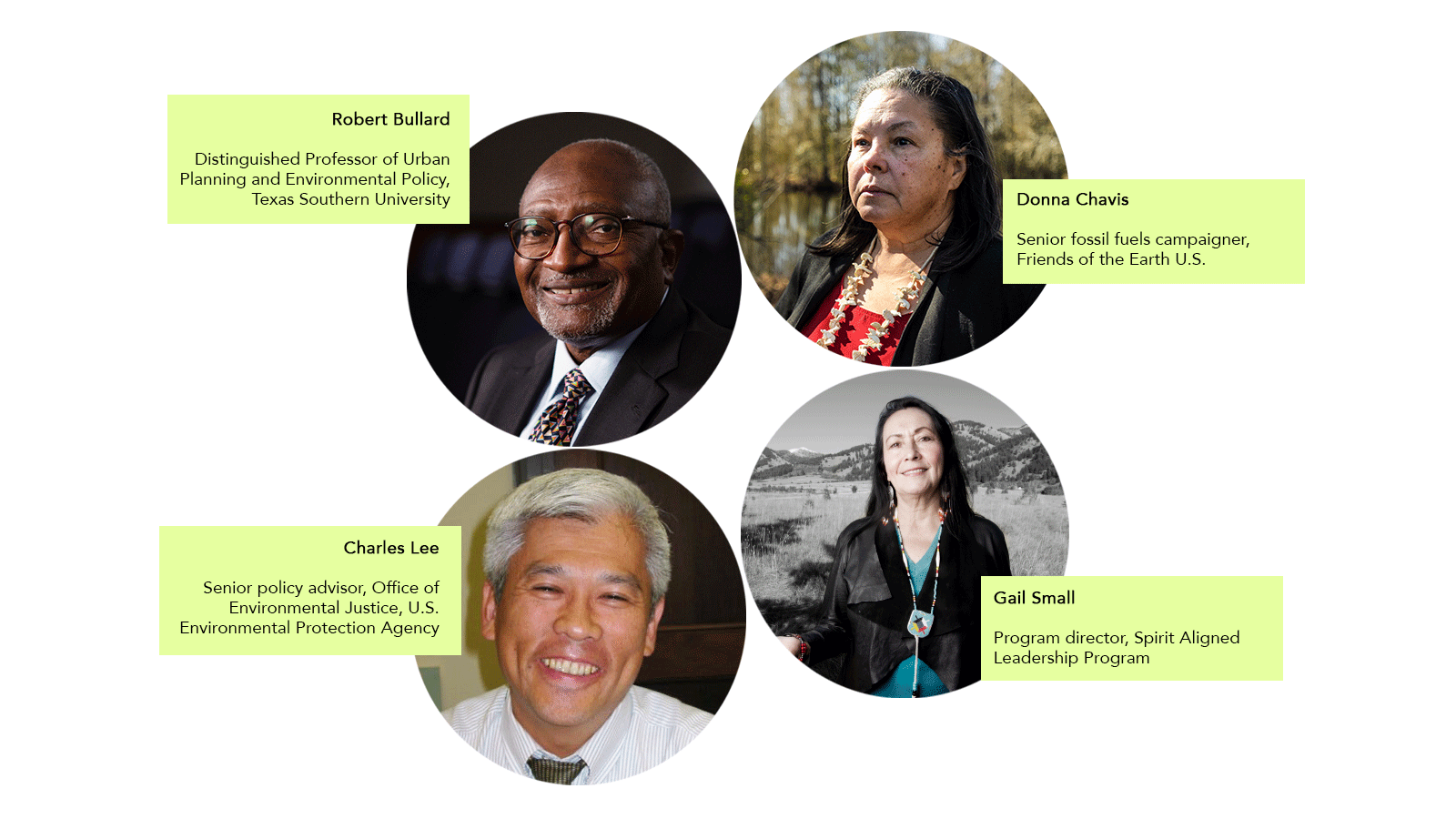

Thirty years later, the 17 principles of environmental justice laid out during the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit are as relevant as ever. The intersection between race and environmental injustices has been recognized by the federal and state governments, and a growing number of people understand certain groups are more vulnerable to the devastating effects of environmental degradation and climate change due to historical injustices. On the 30th anniversary of the summit, we talked to four of its key figures to understand the legacies of the watershed moment, and what challenges still lie ahead for environmental justice.

Q. How did this event change the environmental movement in the United States?

A. Robert Bullard: The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit was groundbreaking in that people of color basically decided we wouldn’t wait for white environmental groups to ride in on a white horse and save us. Our communities were being poisoned, but many of the environmental groups did not see our issues as part of their agenda. So we pushed back. A couple of them showed up at our summit, and we said that people of color will no longer take a backseat when it comes to advancing our policies. When we see environmental racism, we will call it what it is, and we will fight to dismantle structural and systemic racism in this country. That was 1991. It has taken almost 30 years for that lens to become the dominant lens. For me that was a power shift. Our EJ lens was a footnote. Today, it’s the headline.

Donna Chavis: The event’s legacy is not just symbolic, it is concrete. The executive order they used for the implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act, which came out of the Clinton administration, grew out of the summit and the organizing work that happened post-summit. If you look at the structure of the [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency] now, and trace back to when its focus began to include environmental justice, it was post-1991 summit.

Q. How has the EJ movement changed and evolved since the summit?

A. Charles Lee: The call to action from the summit was to go back to our communities and to organize, and all the people that showed up took that to heart. Particularly the people from community organizations. They went back to all parts of the country and organized over several decades to build power at home, to really deepen the roots in terms of those struggles. In that process, it began to really impact local dynamics, and then regional, and now national over this period of time.

Gail Small: There was steady progress for the environmental justice movement going back 30 years, using administrative and legal methods to get our voices heard. All of that was wiped out when Trump came into office. He eroded all of the administrative protocols for what we called the Administrative Procedure Act — how agencies operate and how they’re required to participate in a public notice to those affected. That in and of itself was a wake up call to the environmental justice movement that the progress we’ve made is fleeting. The momentum is still there. That’s important to say. But a lot depends on who gets into political office, who has the power to unilaterally throw out decades of precedent and decades of rulemaking.

Q. How are today’s challenges different or similar from the ones you had in 1991?

A. Robert Bullard: The underlying condition that creates environmental health, housing, energy, climate, and food and water insecurity challenges in communities of color, disproportionately, is racism. Systemic racism is still a major challenge, a barrier that we have yet to dismantle. And it was the same challenge in 1991. Our communities are still getting poisoned, and our institutions and organizations are still not getting the funding they need. The fact that racism is so ingrained in American DNA, that means that when we come up with solutions, they need to include a whole-system approach.

Donna Chavis: They’re not different challenges, I just think they’ve been magnified. For me, you can’t have anti-racism without anti-environmental racism. You can’t have racial justice without environmental justice. And yet, so often, I find in the environmental justice arena, fear and timidity, sometimes, of being too vocal, because you don’t want to seem like you’re trying to overshadow other issues. We’re all in the same boat when it comes to dealing with unjust systems.

Q. What gives you hope after 30 years of working on EJ issues?

A. Robert Bullard: In 1991, when we say we are fighting environmental racism, they would run from us, it was almost like we were carrying a match and gasoline. But today, there are some folks and organizations, institutions or politicians standing with us trying to really cut out this cancer that’s holding back our nation.

Charles Lee: Environmental justice issues were originally not heard at all, even at the time of the summit. It wasn’t until events like Hurricane Katrina that raised this issue in the mainstream American consciousness. And then certainly Flint, Michigan, made environmental injustice real to people. Now, it’s totally different — it’s expanding in terms of getting attention in the federal and state government. That creates all kinds of new opportunities to leverage resources. The idea that 40 percent of the benefits over a set of federal programs should go to disadvantaged, overburdened, or environmental justice communities — that’s a huge sea change in terms of how we do our work.

We have the opportunity to really make environmental justice part of the regulatory process. In the past we have not been able to fully analyze disproportionate impacts, particularly cumulative impacts. That’s a challenge that has been there, but I think it’s the first time people are directly looking at it.

Gail Small: The environmental justice movement, the tribal sovereignty movement, that momentum continues. And it continues with us mentoring and teaching younger generations our knowledge and our experiences. What gives me a lot of hope is that younger people are very open minded. They’re very aware of the environmental movement. They’re very aware of the climate crisis, and they don’t see it as something that is separate from their daily lives.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Mark Armao, Jena Brooker, and Emily Pontecorvo contributed reporting to this story.