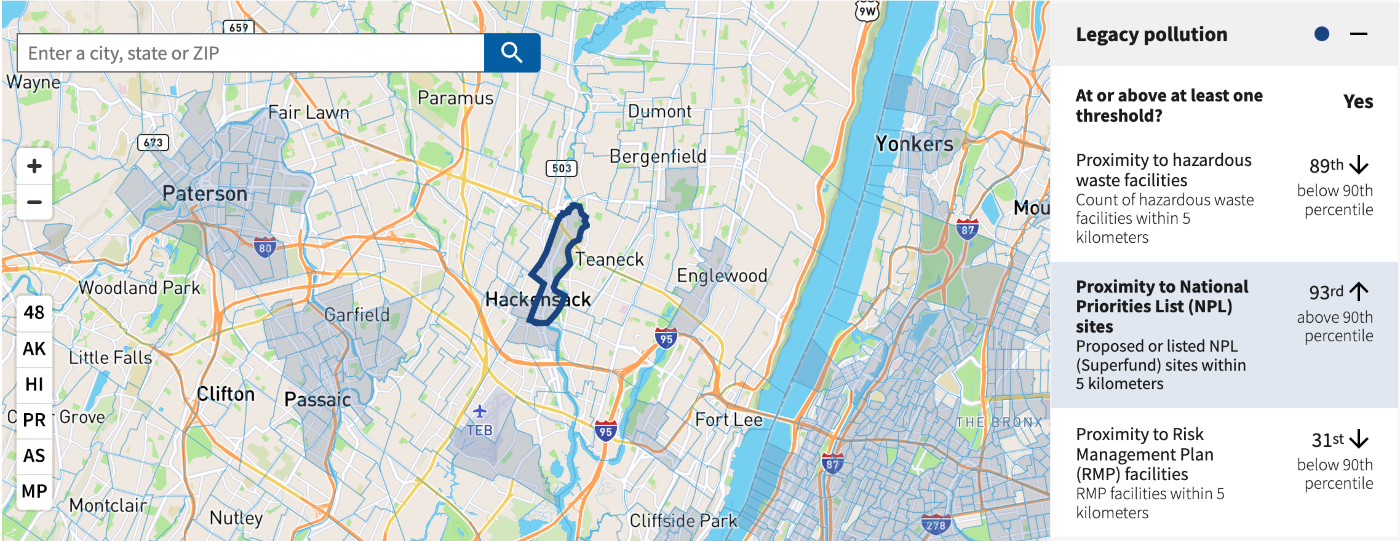

In February, the White House published a beta version of its new environmental justice screening tool, a pivotal step toward achieving the administration’s climate and equity goals. The interactive map analyzes every census tract in the U.S. using socioeconomic and environmental data, and designates some of those tracts as “disadvantaged” based on a complicated formula.

Once finalized, this map and formula will be used by government agencies to ensure that at least 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal climate, clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing, clean water, and other programs are directed to disadvantaged communities — an initiative known as Justice40.

But this new screening tool is not only essential to environmental justice goals. It’s also a pioneering experiment in open governance. Since last May, the software development for the tool has been open source, meaning it was in the public domain — even while it was a work in progress. Anyone could find it on GitHub, an online code management platform for developers, and then download it and explore exactly how it worked.

In addition, the government created a public Google Group where anyone who was interested in the project could share ideas, help troubleshoot issues, and discuss what kinds of data should be included in the tool. There were monthly “community chats” on Zoom to allow participants to have deeper discussions, regular “office hours” on Zoom for less formal conversations, and even a Slack channel that anyone could join.

All of this was led by the U.S. Digital Service, or USDS, the government’s in-house staff of data scientists and web engineers. The office was tasked with gathering the data for the tool, building the map and user interface, and advising the Council on Environmental Quality, or CEQ, another White House agency, in developing the formula that determines which communities are deemed disadvantaged.

These were unprecedented efforts by a federal agency to work both transparently and collaboratively. They present a model for a more democratic, more participatory form of government, and reflect an attempt to incorporate environmental justice principles into a federal process.

“Environmental justice has a long history of participatory practices,” said Shelby Switzer, the USDS open community engineer and technical advisor to Justice40, citing the Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing, a sort of Bible for inclusivity in environmental justice work. “Running this project from the start in as open and participatory of a way as possible was important to the team as part of living environmental justice values.”

The experiment gave birth to a lively community, and some participants lauded the agency’s effort. But others were skeptical of how open and participatory it actually was. Despite being entirely public, it was not widely advertised and ultimately failed to reach key experts.

“Open source” doesn’t just mean allowing the public to look into the mechanics of a given software or technology. It’s an invitation to tinker around with it, add to it, and bend it to your own needs. If you use a web browser with extensions like an ad blocker or a password manager, you’re benefiting from the fact that the browser is open source and allows savvy developers to build all sorts of add-ons to improve your experience.

The Justice40 map is intended to be used similarly. Environmental organizations or community groups can build off the existing code, adding more data points to the map that might help them visualize patterns of injustice and inform local solutions. The code isn’t just accessible. The public can also report bugs, request features, and leave comments and questions that the USDS will respond to.

The USDS hoped to gather input from people with expertise in coding, mapping technology, and user experience, as well as environmental justice issues. Many similar screening tools have already been developed at the state level in places like California, New York, Washington, and Maryland.

“We know that we can learn from a wide variety of communities, including those who will use or will be impacted by the tool, who are experts in data science or technology, or who have experience in climate, economic, or environmental justice work,” the agency wrote in a mission statement pinned to the Justice40 data repository.

Garry Harris, the founder of a nonprofit called the Center for Sustainable Communities, was one such participant. Harris’ organization uses science and technology to implement community-based sustainability solutions, and he found out about the Google Group from a colleague while working on a project to map pollution in Virginia. “As a grassroots organization, I feel really special to be in the room,” he said. “I know in the absence of folks like us who look at it both from a technology and an environmental justice lens, the outcomes are not going to be as beneficial.”

Through the Google Group and monthly community chats, the agency solicited input on finding reliable data sources to measure things like a community’s exposure to extreme heat and to pollution from animal feedlots.

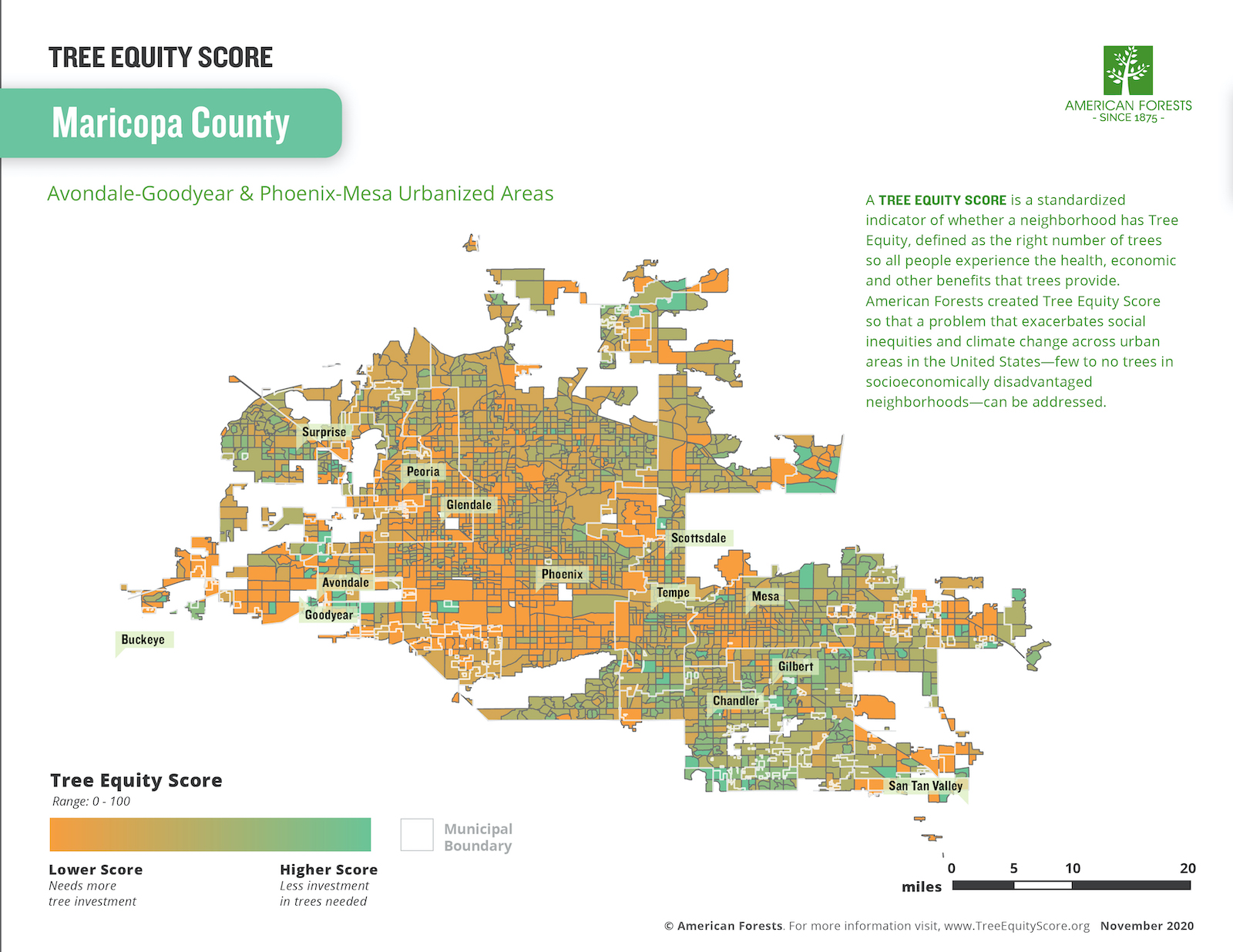

“That level of transparency is not common,” said Rohit Musti, the director of software and data engineering at the nonprofit American Forests. Musti found out about the open-source project through some federal forest policy work his organization was doing and became a regular participant. He said he felt the USDS did a lot of good outreach to people who work in this space, and made people like him feel like they could contribute.

Musti submitted American Forests’ Tree Equity Score, a measure of how equitably trees are distributed across urban neighborhoods, to the Justice40 data repository. Although the Tree Equity Score data did not make it into the beta version of the Justice40 screening tool, it is included in a separate “comparison tool” that the USDS created.

Right now there’s no user-friendly way to access this comparison tool, but if you’re skilled in the programming language Python, you can generate reports that compare the government’s environmental justice map to other established environmental justice screening methods, including the Tree Equity Score. You can also view all of the experiments the USDS ran to explore different approaches to identifying disadvantaged communities.

But to Jessie Mahr, director of technology at the nonprofit Environmental Policy Innovation Center, who was also active in the Justice 40 open-source community, the Python fluency prerequisite signifies an underlying problem.

“You can call it open source,” she said, “but to which community? If the community that’s going to be using it cannot access that tool, does it matter that it’s open source?”

Mahr said she respected what the USDS team was trying to do but was not convinced by the result. She said that relatively little of the discussion and information sharing that went on in the Google Group and monthly community chats seemed to make it into the tool. While the USDS staffers running the effort seemed genuinely interested in gathering outside expertise, they weren’t the ones making the final decisions — CEQ was. And the open-source platforms did not offer any window into what was being conveyed to the decision-makers. Mahr was disappointed that the beta tool that was released to the public in February did not reflect the research that outside participants shared related to data on extreme heat and proximity to animal feedlots, for example.

Switzer, the USDS technical adviser, told Grist that CEQ was part of the effort from the start. They said that a senior advisor to CEQ regularly participated in the Google Group and that learnings from the group were brought to CEQ “in various formats as relevant.”

CEQ has not explained the logic behind the choices embedded in the tool, like which data sets were included, though it is planning to release more details on the methodology soon. The agency is also holding listening and training sessions where the public can learn more.

But it was also strange to Mahr that despite the high profile of the White House’s Justice40 initiative in the environmental justice world, the open-source efforts were not advertised. “I never heard about it through any other channels working on Justice40 that I would have expected to,” said Mahr. “I enjoyed participating in the USDS’s team’s efforts and don’t think they were trying to hide them,” she added in an email. “I just think that they didn’t have the license or capacity to really promote it.” Like the other participants Grist spoke to, Mahr heard about the project through word of mouth, from a colleague who knew the USDS team.

Switzer confirmed that the USDS team largely relied on word of mouth to get the word out and noted that they did reach out to people who had expertise working on environmental justice screening tools.

But it’s clear that the word-of-mouth system failed to reach key voices in the field. Esther Min, a researcher at the University of Washington who helped build Washington’s state-level environmental justice screening tool, told Grist that she had met with folks from CEQ about a year ago to talk them through that project. But she hadn’t heard anything about the Google Group until February, after the beta version of the federal tool was released. Alvaro Sanchez, the vice president of policy at the nonprofit Greenlining Institute and a participant in the development of California’s environmental justice screening tool, said he had no idea about the group until Grist reached out to him in March.

Sanchez was frustrated, especially because for months the government offered very little information about the status of the tool. On one hand, he understands that the USDS team may not have had the capacity to reach out far and wide and invite every grassroots organization in the country. “But the bar that I’m setting is actually fairly low,” he said. “The people who have been working on this stuff for such a long time, we didn’t know what was happening with the tool? To me, that indicates that the level of engagement was actually really minimal.”

Sacoby Wilson, a pioneer of environmental justice screening tools based at the University of Maryland, received an invite to the group from another White House agency called the Office of Management and Budget last May. He said he didn’t get the sense that the group was hidden but agreed that the USDS hadn’t done a great job of getting the word out to either the data experts who build these environmental mapping tools at the state level, or the community organizations that actually work on the issues that the tool is trying to visualize.

But Wilson pointed out that the federal government used another channel to gather input from communities: The White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, which is made up of leaders from grassroots organizations all over the country, submitted extensive recommendations to CEQ on which considerations should be reflected in the screening tool. To Wilson, an overlooked issue was that the Advisory Council didn’t have enough environmental mapping experts.

In response to a question about whether USDS did enough outreach, Switzer said the agency was still working on it. “We hope to continue to broaden this kind of community engagement and making the open source group as inclusive and equitable as possible.

“Of course, it has been a learning experience as we’re kind of pioneers in this as a government practice!” they also said.

The tool is still in beta form, and CEQ plans to update it “based on public feedback and research.” The public can attend CEQ listening sessions and submit comments through the Federal Register or through the screening tool website. The discussion in the open-source Google Group is also ongoing, and the USDS team will continue to host monthly community chats as well as weekly office hours.

In a recent email announcing upcoming office hours, Switzer encouraged people to attend “if you don’t know how to use this Github thing and would like an intro :)”

This story has been updated to clarify the types of federal programs included in the Justice40 initiative.