This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

For four out of five people on the planet, climate change made July, the globe’s hottest month on record, even hotter. And in the United States, nowhere has been more consistently hot this summer than Phoenix, which endured 31 consecutive days at 110 degrees Fahrenheit or above — the hottest month, on average, in any U.S. city on record. For 16 days, nighttime temperatures in the metropolis of 1.6 million people didn’t dip below 90 degrees, a telltale sign of climate change.

Extreme heat comes with serious public health consequences. Heat causes more deaths in America than any other weather-associated hazard. More than 11,000 people have died from heat since 1979, which is almost certainly an underestimate. Officials suspect seven people may have died due to heat in state and national parks in the Southwest this summer — an unusually high number for June and July.

In Arizona, one of the states where heat-related deaths are most common, the number of fatalities in metro-area Phoenix — 39 deaths connected to heat so far — could surpass last year’s total, potentially by a large margin. The Maricopa County Department of Public Health reported that there may have been 312 more deaths connected to heat in the county this year, all of which are under investigation.

The emergency in Arizona is a harbinger of crises to come: Climate-fueled heat is quickly becoming an omnipresent killer.

Emergency room doctors in Phoenix are on the front lines of this challenge. This summer, physicians in Arizona have been inundated with patients suffering from heat-related illnesses, but they’ve also been seeing higher volumes of patients with chronic diseases exacerbated by heat. And burn units in the state are tending to people with severe contact burns from blazing asphalt and other hot surfaces.

All summer, Kara Geren and Frank Lovecchio, two emergency medicine physicians in Phoenix, have noticed that no matter what a patient comes in for — whether it’s chest pain or a chronic health condition such as diabetes — they also likely need fluids. “What surprised us is, even people that came in for completely unrelated things are dehydrated,” said Geren, who works at Valleywise Health Medical Center in central Phoenix. “It’s just so hard to stay hydrated.”

The patients presenting with dehydration add to the considerable number of people coming to the ER with symptoms consistent with heat-related illness: heat rashes, cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, and the most severe form of heat sickness, heat stroke.

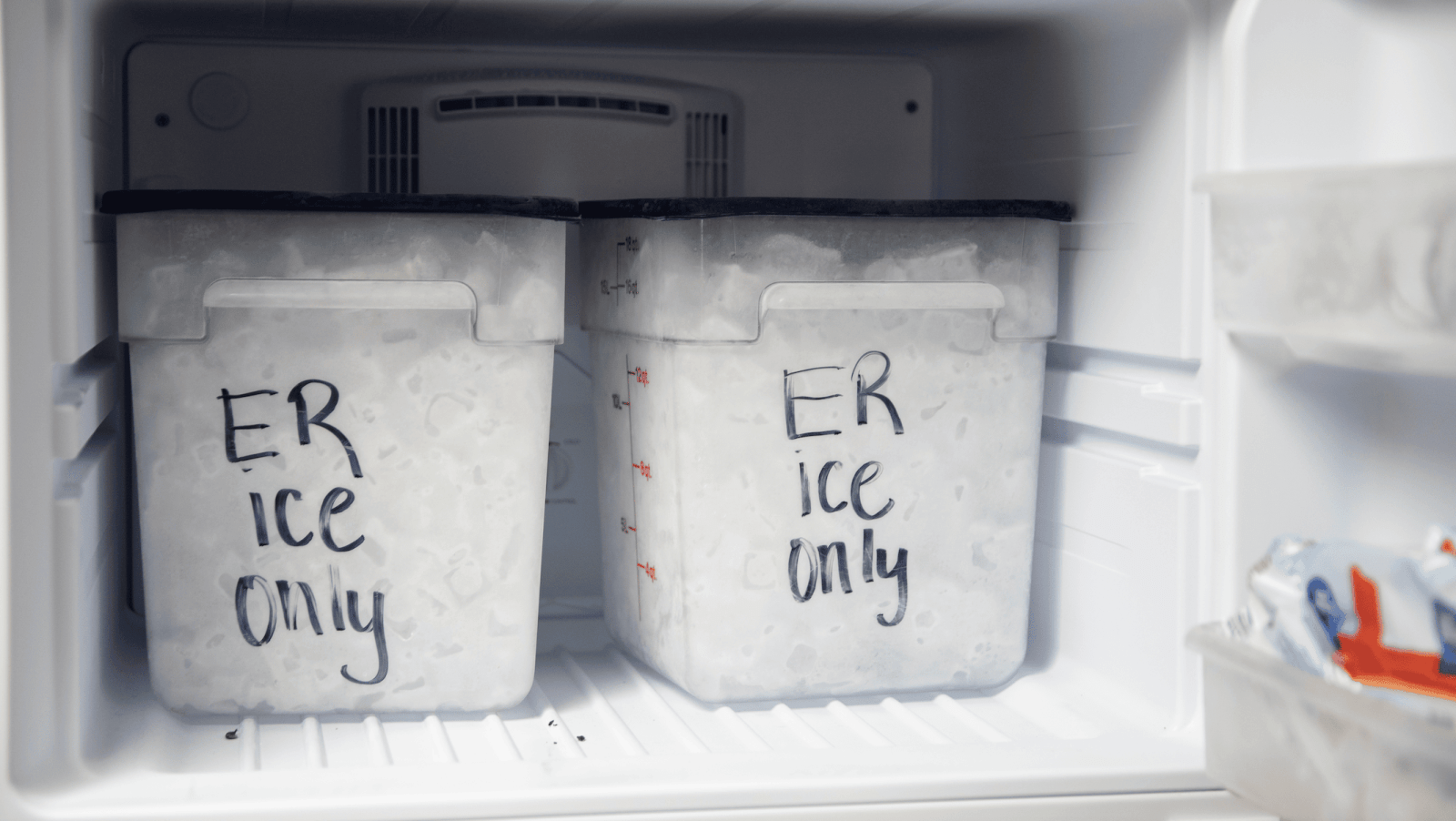

Loveccio, who is affiliated with Valleywise and also works in a few free-standing emergency departments in the city, has been immersing patients in large tubs of cold water and even zipping them into body bags filled with ice to cool them down. Chilling intravenous fluids and oxygen before administering them to patients also helps, he said.

But heat leaves an impact on the body no matter what, especially if the person is elderly, works outside, or uses drugs like opioids.

“A very large percentage of our population has issues with mental illness, drugs, and alcohol,” Geren said. “Once you put those into the mix, people’s sensation of, ‘It’s hot — I need to get out of the heat’” is affected, she noted. Part of the problem is the heat hasn’t been dissipating at night, which would give people, particularly Maricopa County’s approximately 9,600 people without housing, a reprieve.

“It’s just never cool,” Geren said. “This is by far the worst year that we’ve ever seen.”

On a 100-degree Fahrenheit day, asphalt in direct sunlight will heat up to 160 degrees — more than hot enough to give someone a bad burn. Geren recently treated an elderly woman who fell on the pavement outside her house and couldn’t get up. She was found hours later and rushed to the emergency room with severe burns. “Our burn unit is very, very busy,” Lovecchio said. “If you walk across the street barefoot, there is no doubt that you would get at least a second degree, if not a third degree, burn to your feet.”

Both doctors worry about what the future might hold for Phoenix and whether they can continue to live in the state.

“This is my home, it’s been so for 30 years or so, and I hope I live here forever,” Lovecchio said. “But a lot of people have that billion-dollar question: Is it going to become unlivable? I think it’s pretty close this summer.”