This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

More than a decade ago, two climate scientists defined what they considered at the time to be the upper limit of human survivability: 35 degrees Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit, at 100 percent humidity, also known as the wet-bulb threshold. In those conditions, a person, no matter who they are or where they live, cannot shed enough heat to stay alive for more than a few hours. The scientists’ operating assumption was that carbon emissions would need to warm the planet 5 to 7 degrees C (9 to 12.6 degrees F) before the world exceeded the wet-bulb threshold every year. Since then, more advanced work has demonstrated the world only needs to warm by about 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) before heat waves in the hottest parts of the world first cross that survivability line.

But just looking at the survivability threshold doesn’t paint the full picture of heat-related risk. The theoretical experiment underpinning that threshold was based on two assumptions: that humans are fully adapted to heat, or used to hot conditions, and that people do everything in their power — seek out shade, fan themselves, and douse themselves with water — to stay cool during an extreme heat event. The reality is that death can occur long before wet-bulb conditions are eclipsed for a variety of reasons that have to do with age, health, adaptation, and access.

A study published in Science Advances this week used a more realistic threshold to determine when and where the world will become dangerously hot for humans. The researchers, from the University of Oxford and the Woodwell Climate Research Center, used a framework called the “noncompensable heat threshold,” the conditions under which a human being can no longer maintain a healthy core temperature without taking action to cool off. Six hours of unmitigated exposure to these temperatures would be sufficient to cause death. This threshold can be reached under different combinations of air temperature and humidity — the hotter the temperature, the less humidity needed to cross the limit. At 40 degrees C (104 degrees F), for example, you need about 50 percent relative humidity to cross the noncompensable threshold.

The researchers found that parts of the world have already surpassed this threshold. They identified 21 weather stations that clocked conditions exceeding the noncompensable threshold between 1970 and 2020, mainly along coastlines in the hottest regions of the planet such as the Persian Gulf and South Asia. Even more people will face such conditions as the planet continues to warm from fossil fuel combustion.

Christopher W. Callahan, an earth systems scientist at Dartmouth College who researches health and heat and was not involved in the research, called the study’s results “striking.” “Some locations are already experiencing these critically hot conditions,” he said. “They’re not just a forecast from a climate model, they’re directly observable using quality-controlled weather station observations.”

As more countries experience abnormally high temperatures every summer, using pure “survivability” as the metric for when heat-related mortality will occur is a dangerous proposition. Death can occur much sooner than that.

At the wet-bulb threshold, “no matter what you do short of air conditioning, you face lethal risk,” said Carter Powis, a researcher at the University of Oxford and the study’s lead author. “The threshold we looked at, noncompensable heat, is you face lethal heat risk unless you do something. Meaning there are still ways you can survive above this threshold such as using a fan, drinking cold water.” Any conditions between these two definitions are what the study’s authors call the “danger zone.” Whether someone dies when they’re in that zone depends on what cooling strategies are available to them and how well adapted they are.

The study shows that, under current climate change conditions, 8 percent of the globe by land area experiences conditions that are in the danger zone once every decade. At 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) of warming, a climate change benchmark the world is currently on track to exceed, more than a quarter of the world will experience these conditions at least once a decade. The percentage of the planet that will experience potentially fatal heat continues to grow the more climate change accelerates.

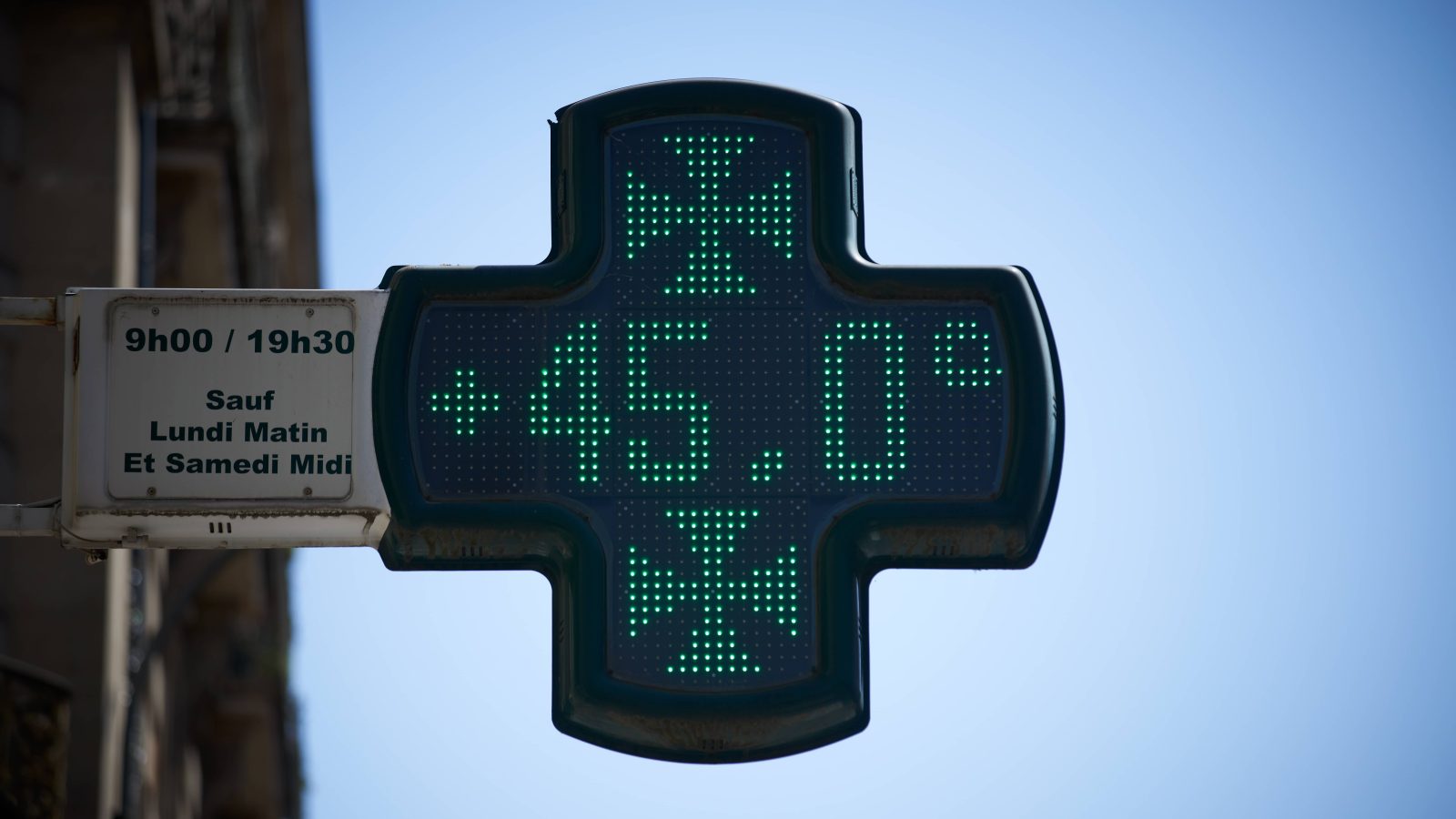

It’s not just the hottest regions of the planet that are at risk. In the U.S., the Midwest and East Coast could see rapid increases in noncompensable heat exposure. The same is true for the Mediterranean region up north through Europe. These are areas that are not used to extreme heat.

“While prior research has indicated that fatal wet bulb temperatures will occur more often in the most populated and poor regions of the planet, this research suggests that wealthier countries in North America and Europe will also face increasingly dire heat waves,” Cascade Tuholske, a geographer at Montana State University who was also not involved in the study, told Grist.

For Powis, the biggest takeaway is that communities need to be aware that past heat-related mortality events are not a good way to gauge future risk. As the planet warms, the past will become an increasingly poor metric for looking at the future. “The danger is, in the near term, in the next decade or two decades, you have one of these extreme heat waves that departs from the historical maximum by a substantial amount, crosses this threshold, and causes wide-scale mortality,” Powis said. “Everything is fine until suddenly it’s not.”