Hundreds of thousands of Americans have dropped their flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program, or NFIP, since last October, E&E News found in a review of federal records. The sharp decline in coverage comes after the Federal Emergency Management Agency overhauled the program’s insurance pricing system, a move that was meant to make premiums more accurately reflect the flood risk of a property.

When the agency reviewed the NFIP last year, it discovered inequities in the way that insurance premiums were priced. Homes in the less risky areas of flood zones were overpaying for their premiums, and shouldering a higher burden of the costs of flood risk. The system overhaul was meant to address these inequalities, adjusting premium rates according to level of risk.

“[W]e have a responsibility to make sure that we have actuarily sound, fair, and equitable rates. And so that’s what’s driving the change,” NFIP senior executive David Maurstad told CNBC last year.

While this restructuring has caused some homeowners to see decreases in their insurance premiums, others saw their rates spike to over $4,000 annually from just around $700, according to Jeremy Porter, chief research officer at First Street Foundation, a nonprofit research group that quantifies and communicates climate risks.

E&E News found that the total number of NFIP policies declined by nearly 9 percent, from 4.96 million to 4.54 million, between the end of September 2021 and the end of June 2022.

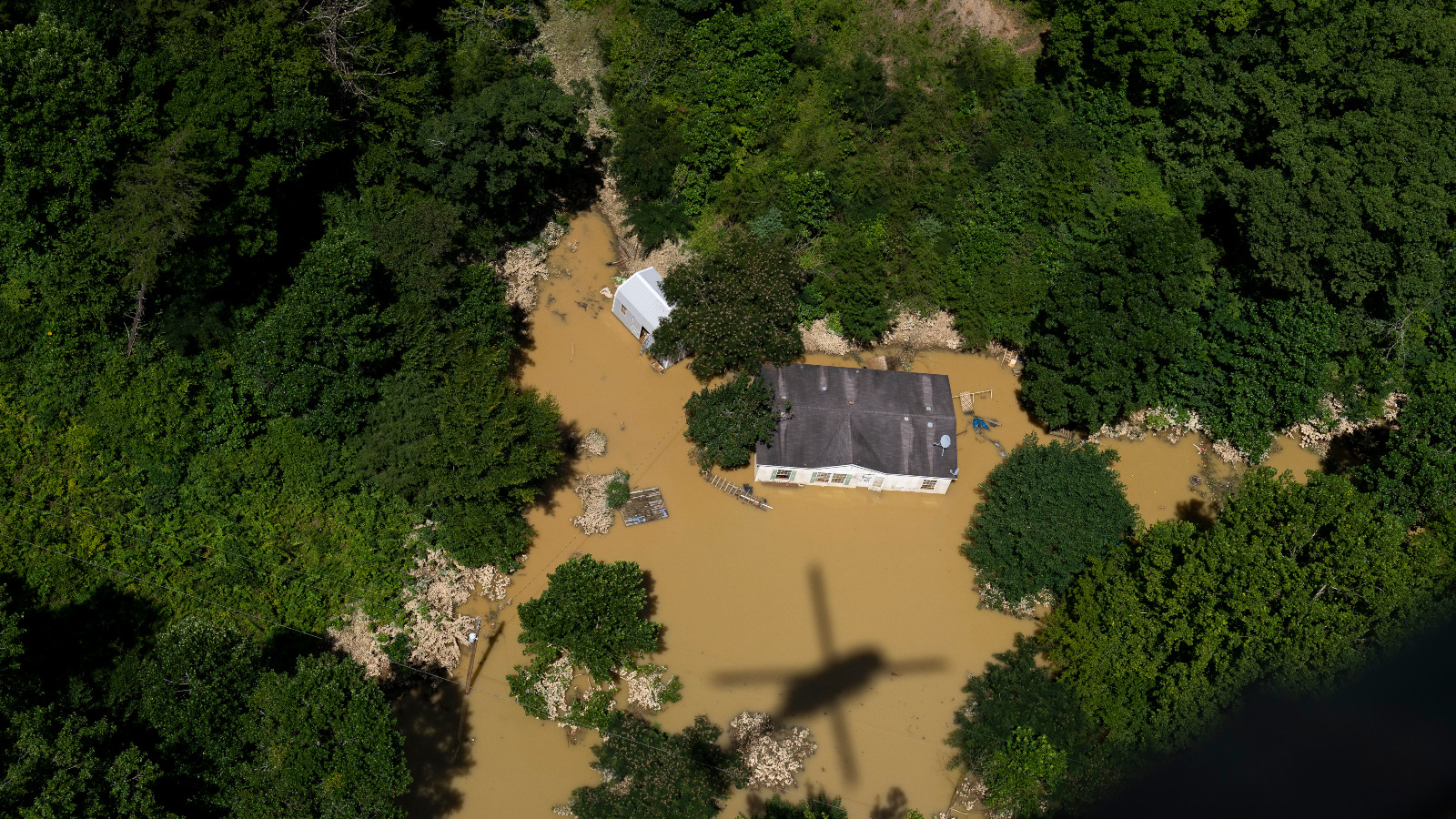

The drops in coverage come at a time when it is more important than ever for people living in flood zones to buy insurance. FEMA estimates that climate change will cause the size of areas with a high flood risk to increase by 55 percent along the nation’s coastlines and up to 45 percent along major river systems by the end of the century.

Sarah Pralle, an associate professor of political science at Syracuse University, said that while the preliminary numbers of dropped policies are concerning, they’re part of a wider problem that extends back before the NFIP’s restructuring. Americans living in flood-prone areas tend not to buy insurance, making premiums higher for those who do, because the insurance pool is smaller.

This problem could be partly addressed through enforcement: Although federal law requires homeowners paying off federally backed mortgages in high-risk areas to purchase flood insurance, many choose not to, or drop their policy after a few years.

But the bigger problem, she believes, is rooted in FEMA’s flood maps, which depict current levels of disaster risk using data from the past, instead of projections for the future.

“You might buy a house just outside the edge of a flood zone, thinking you’re safe, but you’re going to have that mortgage for 30 years,” she said. “And probably within 30 years your house is going to be in a flood zone.”

The solution, Pralle believes, is to adjust FEMA’s flood maps to encompass a larger number of people, thereby widening the insurance pool and bringing down premiums for everyone.

But requiring more people to buy flood insurance is a politically unpopular policy that risks overburdening low-income homeowners who are already struggling to pay their mortgages. Recognizing this, Pralle said an equitable national flood insurance program would offer subsidies to low income families to incentivize them to seek coverage.

After all, she said, it is in everyone’s best interest to have flood insurance. Individuals without coverage must often rely on FEMA disaster relief funds, which are typically only several thousand dollars, as opposed to the up to $250,000 that NFIP policyholders may receive for structural damage to a single-family home.

“If you look at outcomes, people with insurance do a lot better after disasters,” she said. The goal should be to make sure low-income homeowners have access to those better outcomes. “Subsidize those premiums so that they have that security and they don’t lose everything,” Pralle said. “I don’t think the solution is just don’t make people buy insurance.”