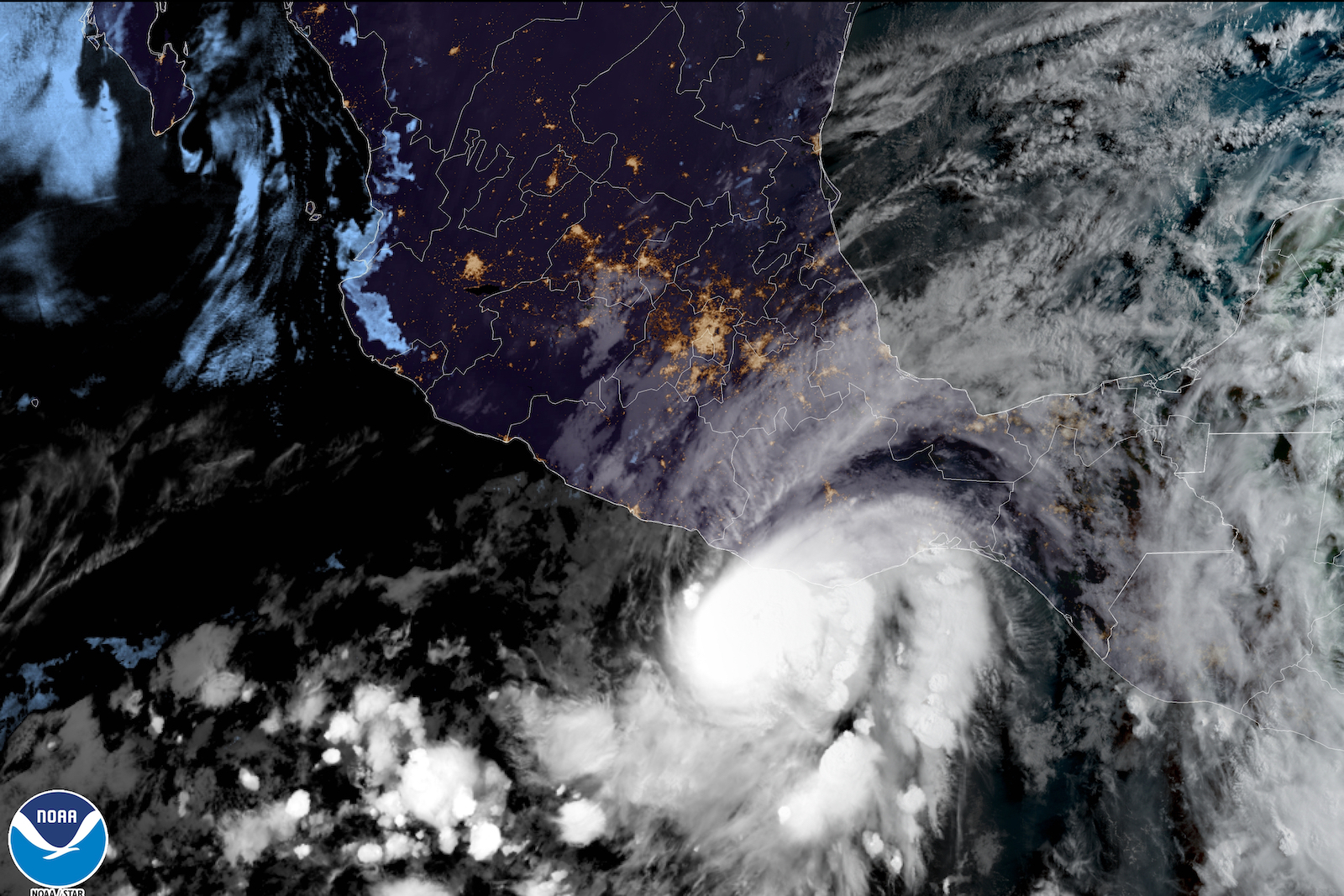

Hurricane Agatha, the first named storm of this year’s Pacific hurricane season, slammed into the coast of southwest Mexico on Monday, bringing coastal flooding, heavy rain, and sustained winds of 105 miles per hour. It was the strongest storm to hit Mexico’s Pacific coast in the month of May since record keeping began in 1949.

The National Hurricane Center predicts that the remnants of the storm will cross into the Gulf of Mexico or Caribbean, and could spawn the first named storm of the Atlantic season, which kicks off June 1. This comes a week after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, issued its annual hurricane season outlook, forecasting “above-average” hurricane activity in the Atlantic for the seventh year in a row.

Agatha rapidly intensified into a Category 2 hurricane off the coast of Mexico on Sunday and made landfall in the state of Oaxaca the next day. The torrential rains caused mudslides, blocking two highways in Oaxaca, and some towns lost power and telephone lines. At least three people were killed.

The storm weakened as it traveled inland and over mountains, but could gain new life when it reaches the Atlantic. On Tuesday afternoon, forecasters with the National Hurricane Center predicted that what’s left of Agatha will collide with an area of low pressure currently spinning over southeastern Mexico, saying there’s a 70 percent chance that it could turn into a new tropical depression or storm named Alex once it crosses into the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean Sea.

If Agatha does morph into Alex, it will kick off an Atlantic hurricane season that’s expected to be a busy one. NOAA predicts there will likely be 14 to 21 named storms this year, with six to 10 becoming hurricanes with winds of at least 74 miles per hour — including three to six major hurricanes with winds of at least 111 miles per hour. Forecasters attribute the increase in expected hurricane activity to several factors, including the ongoing La Niña, which affects oceanic and atmospheric circulation globally, a strong west African monsoon, which creates wind patterns that can spin up storms across the Atlantic, and warmer than average sea surface temperatures, which can fuel the rapid intensification of storms.

Rising sea surface temperatures are just one way that climate change is influencing hurricanes, according to NOAA. Warmer temperatures mean the atmosphere can hold more moisture, allowing hurricanes to dump more rain. Higher sea levels mean storm surges are inundating more of the coast. A recent study published in the journal Weather and Climate Dynamics found that climate change has “contributed to a decisive increase in Atlantic Ocean hurricane activity” since the 1980s and doubled the chances for extreme seasons like 2020 — when 31 named storms made it the busiest on record.