When American settlers arrived in California 150 years ago, the sprawling Central Valley was home to the largest body of freshwater west of the Mississippi River. Tulare Lake expanded each spring as rain and melting snow filled the valley, growing so large that fisherfolk could sail across its surface to catch terrapin for San Francisco restaurants. But the land barons who took over the region soon drained the lake and covered it in crops, helping make it one of the nation’s most productive agricultural hubs.

Now, as California closes out a historically wet winter, Tulare Lake has reappeared for the first time since 1997. As runoff from several rivers drains into the valley, the homes and streets and fields that sit on the lake bed, which covers 1,000 square miles, are being inundated once again. The flooding will only increase over the next few months as the state’s record snowpack melts, dousing the area with the equivalent of 60 inches of rain.

Tulare Lake has always emerged during especially wet years, but the flooding will be worse this time: the region’s powerful agriculture industry has compounded flood risk around the lake by pumping enormous amounts of subterranean groundwater, turning the region into a giant bowl. Farmers overdraw the basin’s aquifer by around 820,000 acre-feet per year, far more water than Los Angeles consumes over the same period, and this pumping has caused the southern Central Valley to sink faster than almost any other place in the world.

Subsidence is occurring throughout California, but the problem is at its worst in the area around Tulare Lake, which is about 200 miles north of L.A. Some cities near the lake bed have sunk by as much as 11 feet over the past half-century. That rapid decline makes homes and crops in the basin much more vulnerable to flooding than when the lake last appeared 35 years ago. What’s more, the levees and channels that control flooding are getting less effective as the land around them subsides.

“Tulare Lake is playing Russian Roulette with flooding, and they just lost,” said Deirdre Des Jardins, an independent researcher and consultant who has studied flood risk in the Central Valley. “Water is flowing differently because of the subsidence, and they don’t have any kind of flood management.”

Even as flood risk has grown due to subsidence, local leaders have rejected the state’s attempts to finance new flood defenses. When California began to draft a statewide flood protection plan after Hurricane Katrina, many counties and flood control districts in the agriculture-dominated Tulare Lake basin declined to participate, denying themselves state funding for new levees and bypass systems.

“The local interests who were there at those meetings were pretty adamant that they did not want to be part of a state level plan,” said Julie Rentner, president of the California-based environmental organization River Partners, who participated in the drafting of the plan. “They felt like they had it under control. Especially in some of the more conservative parts of California, there’s a real concern and real suspicion that the state intervening in the way water is managed will have deleterious impacts on local communities or local economy.”

In other cities, like Sacramento, the state spent billions to improve a network of levees and channels that helps manage runoff, but the Tulare Lake basin has no centralized flood infrastructure at all. Tulare County last updated its flood control master plan in 1972, when land in the area was several feet higher. The only levees in the lake bed are those owned and maintained by local flood control districts, which often lack the capital to make significant improvements. Those structure seem all but certain to fail as the lake reappears over the coming weeks, and some already have.

The officials charged with managing groundwater around Tulare Lake have also resisted the state’s attempts to control the pace of subsidence. Earlier this month, state officials chastised a group of local groundwater control agencies for failing to set “minimum thresholds and measurable objectives” for countering subsidence as required by state law. The agencies had said they wanted to limit the region’s subsidence to between 1 and 2 feet over 20 years, a number so high state officials thought it was a typo.

(Groundwater agencies and flood control districts that represent the Tulare Lake area didn’t immediately respond to interview requests.)

Much of the land on the lake bed is owned by J.G. Boswell, an agricultural company founded by the famous land baron of the same name. Boswell is one of the titans of the Central Valley, and has long been among the largest private farming operations in the world — it grows cotton, tomatoes, wheat, and a variety of other staples on fertile land that used to be underwater. The company maintains pumps and flood cells to protect its crop from inundation, but many of its fields will likely flood later this spring.

But it’s not just farmland that stands to flood. The Tulare Lake basin is home to half a dozen small towns, including Allensworth, the oldest town in California founded by Black people, and Corcoran, which houses a large state prison and a large population of agricultural laborers. Due to the pace of subsidence, these towns grow more vulnerable to flooding with every passing year, and some have already taken on several feet of water this year. Earlier in March, someone sliced a hole in a barrier along a local creek, flooding most of Allensworth.

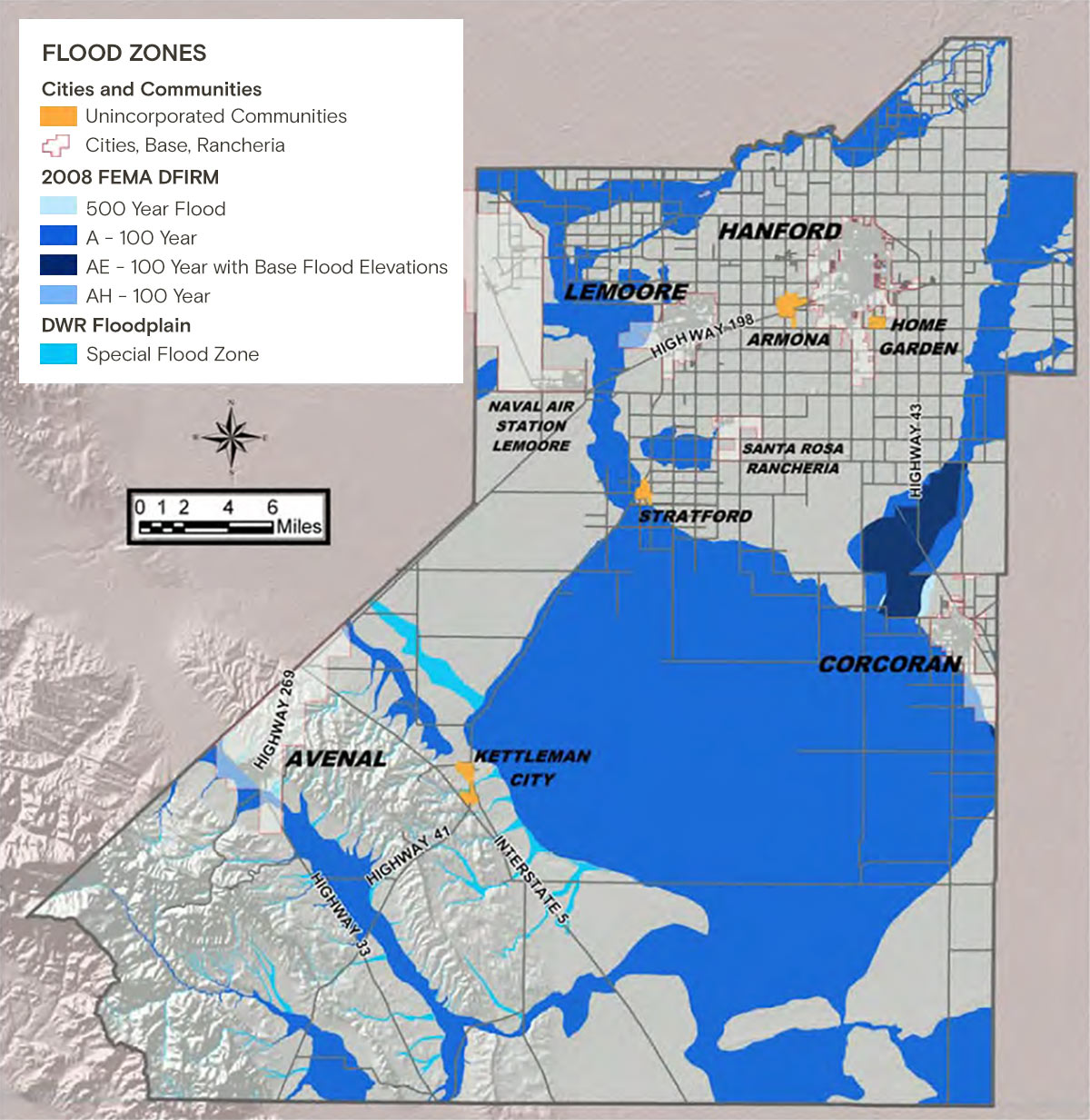

Few people in these towns have flood insurance. Corcoran, one of the largest cities on the lake bed, has a population of around 22,000, but only five of its households participate in the National Flood Insurance Program. Furthermore, the Federal Emergency Management Agency hasn’t updated federal flood maps to account for the past decade of subsidence, so many residents in flood zones may not even be aware of the risk they face.

The worst is yet to come. Snowpack in the southern Sierra Nevada is almost triple the size of an average year’s, and warming weather will send the equivalent of 60 inches of rain toward Tulare Lake. That water will stick around for months or even years; as the lake grows, flooding could expand north toward the city of Fresno more than 40 miles away, putting thousands of homes and farms at risk. The lake bed also contains facilities like a sewage sludge composting plant that could leak or rupture as the area fills with water.

The result is a brutal irony. Draining Tulare Lake made it possible for the agricultural industry to thrive in the southern Central Valley, but that same industry has made the region more vulnerable than ever as the lake returns.