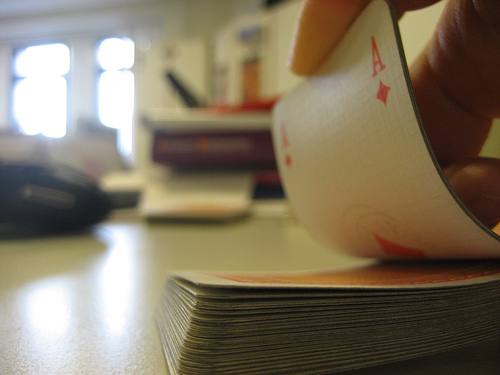

A two-week Food Bill rewrite stacks the deck against good-food advocates.Photo: ccarlsteadLast month, I wrote that prospects for reforming the Farm Bill were dim. My prior assessment is turning out to be outrageously optimistic.

A two-week Food Bill rewrite stacks the deck against good-food advocates.Photo: ccarlsteadLast month, I wrote that prospects for reforming the Farm Bill were dim. My prior assessment is turning out to be outrageously optimistic.

Typically, passage of the Farm Bill occurs every five years and involves a lengthy process of hearings, constituent meetings, and (sad but true) many a high-priced meal on the tab of some lobbyist or other — followed by detailed negotiations between the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. It has also often been seen as an opportunity to — as one recent action alert put it — change the food system by supporting small farms, investing in rural economies, and “supporting more diversified farming and livestock systems, healthy food access, conservation, and research.”

The next reauthorization was not expected until late in 2012 — if not 2013 — but through an unexpected turn of events, it may be decided much faster, and with even less input from the good food movement than the last one.

And when I say faster, I mean at warp speed. Earlier this week, according to the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, the House and Senate Ag Committees suddenly announced that they would write the entire 2012 Farm Bill in the next two weeks.

This new Farm Bill will also be smaller, thanks to the deal cut to avoid a government default over the summer. In the wake of that agreement, Congress convened a “supercommittee” of House and Senate negotiators that’s required to come up with a plan by this Thanksgiving to cut $1.2 trillion from the deficit over the next decade. Of that total, $23 billion must come from the USDA budget — a number recently recommended by House and Senate Agriculture Committee leaders. There is panic in the fields of Big Ag at such a drastic reduction in farm and food spending.

As well there should be: The prospect of a small group of negotiators who are not beholden to traditional farm interests working behind closed doors to slash farm spending might strike some as a sign that our long national industrial agriculture subsidy nightmare is over. But as Ken Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group (EWG) and an advocate for farm subsidy reform, told me, it’s likely that we will get a “Secret Farm Bill” with “no accountability” for those involved.

No one knows exactly how it will turn out. As one source close to the process told Grist, “there are people betting on all” possible scenarios. But one thing is certain; negotiators are desperately trying to maintain the annual flow of $18 billion in subsidies to the largest farmers who produce commodity crops like corn, soy, and cotton. And while there will certainly be losers, you can count on the fact that there will also be winners.

This is reflected in the proposals currently circulating in Congress, specifically over a set of subsidies known as “direct payments.” Originally designed as a temporary means to get around World Trade Organization restrictions on government support of private industry, direct payments go to large farmers based on past farm yields and acreage. It’s the classic “cash the check whether you grow something or not” kind of subsidy that drives food reformers crazy. Direct payments have particularly benefited large-scale soy and cotton farmers from the South, and were thought to be facing the ax.

But as The New York Times reported, rather than pocketing the savings, farm state reps have proposed a new subsidy in its place — and it may not be much different from the old one. It’s known as a “shallow loss” subsidy, and it would protect commodity farmers from small drops in prices. You know, just to take the edge off.

And while direct payments cost $5 billion per year, if crop prices drop from current levels, the new “shallow loss” program could cost around $4 billion per year. No wonder ag economist (and admitted subsidies critic) Vincent Smith of Montana State University described the proposal as a “bait and switch” on NPR recently.

EWG’s Cook is concerned about another potential problem with the proposed new subsidy. With the current set of farm payments, groups can track exactly how much government support individual farmers receive (as EWG does with its Farm Subsidy Database). But with the “shallow loss” plan, says Cook, “the subsidy lobby” is creating a new “income-guarantee entitlement aimed at the biggest commercial operations” that will likely be “totally opaque to the public.” Which means no more tracking who gets how much.

In sum, the supercommittee process has caused what is often (by congressional standards) an orderly process to devolve into a legislative free-for-all. Whatever happens, the outcome is likely to be hidden by a fog of backroom deals and — this being Congress we’re talking about — bitter recrimination.

Adding to the uncertainty, there’s the very real possibility that the supercommittee will fail to come up with a deal. In that case, a set of cuts will be automatically triggered, which might leave agriculture subsides more or less intact (though the same may not be true of the USDA’s food safety system).

We already know that land and watershed conservation programs will face the worst cuts. And the House GOP wants to kill the small-farmer friendly “Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food” initiative as well. It seems clear that Big Ag is embracing former Obama Chief of Staff Rahm Emmanuel’s advice not to let a good crisis go to waste by aiming a body blow at reform in general and sustainable agriculture in particular.

It’s hard not to be cynical about a process whereby powerful corporate interests divvy up taxpayer dollars like so much pirate’s booty. To switch (and mix) metaphors, Big Ag is circling the limos around its giant pile of cash and hoping for the best. If nothing else, the current farm subsidy “debate” is Exhibit A of the need for Americans to Occupy the Food System — though perhaps this big-time money grab can be read as a sign that Big Ag actually fears the growing Occupy Wall Street movement.

Meanwhile, the EWG, along with the NSAC, are asking people to call their representatives to try to head off the worst kind of deal. And while there’s no telling how this particularly nasty bit of sausage making will turn out, it’s a fair bet that only agribusiness will like the taste

.