Richard Jefferson was talking fast, too fast for me to take notes. He was trying to explain what’s wrong with our food system, and what to do about it, but there was too much to say, and we’d already stretched the lunch hour past its breaking point. He kept moving forkloads of salad toward his mouth, but the food couldn’t swim up the cascade of words. It always ended up back on his plate.

Mark Coulson, 5th World Conference of Science JournalistsRichard Jefferson.

Jefferson talks this way because he’s passionate, and because he’s a polymath. He was on the team of public scientists that created the first transgenic plants (one day before Monsanto did it). He invented a genetic marker that earned him notoriety in the field. Then he became an intellectual property expert and created a framework for open-source biological invention. Now, he’s trying to radically transform the entire system of innovation to make it more inclusive and local: He wants a system that empowers farmers in Africa to invent their own solutions, rather than looking to multinational corporations for fixes.

This sounds like it falls somewhere on the spectrum between shooting at the moon and tilting at windmills, but he’s been able to persuade some serious funders — the Gates Foundation, the Lemelson Foundation, and others — to back him.

“The real problem with GMOs is not about science, it’s about business models,” he said. Actually, he said, the problem isn’t limited to GMOs: The real problem is that the people who need new solutions most, like farmers in developing countries, are isolated in a system that discourages ground-level innovation. Instead, we have a small group of companies in rich countries, with a stranglehold on patents, designing all the solutions to fit their own business models. This system works primarily to bring in money for these companies, to maintain their privilege, and to exclude competition.

So are patents the problem?

They’re a big part of it, but, patents aren’t intrinsically bad, Jefferson said. The whole point of the patent system was to get people to share their secrets. The very word patent comes from the Latin patere: to lay open. You tell the world how to make your invention, and in return, the people who use it have to work out a deal with you. If someone uses your invention without your permission, you can sue them — but only for a while, and only in the country where you have the patents.

The problem is that the patent system has grown so complex that only a few experts understand it. It’s impossible for normal people to navigate the patent thickets to discover the treasures there, or see the dangers. And these days everything from a cellphone to a seed requires dozens of separate patents for the component parts. The solution, he said, is mapping it out: what he calls “innovation cartography.”

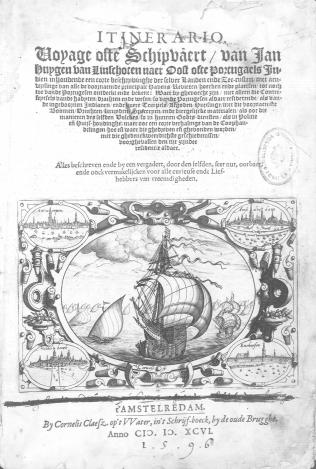

At this point, Jefferson could have tried to convince me by trotting out arguments in the abstract, but he didn’t do that. Instead, he decided to tell the story of the Dutch clerk who stole the Portuguese maps.

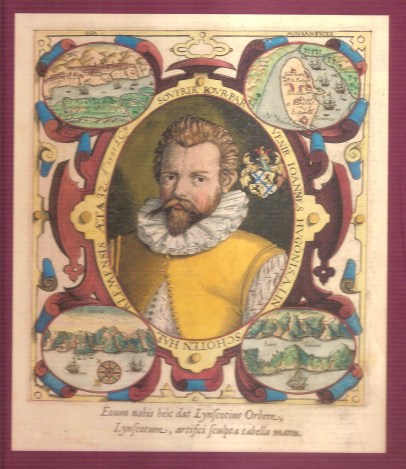

Jan Huyghen van Linschoten.

In the 16th century, the Portuguese had the best maps. Well, the Portuguese and the Spanish (“makes a better story if you focus on the Portuguese,” he said). In any case, the Iberian peninsula controlled all the information needed to send merchant ships to Asia (and, to a large extent, the New World as well). The Iberians had invested heavily in research and development, sending out De Gama, Magellan, Dias, Columbus, all those explorers to map the world. And because they were the only Europeans with reliable maps of the East Indies — these maps were state secrets — the Iberians had a monopoly.

Once this monopoly was in place, three things happened: The Iberians became rich; they pillaged their colonies with increasing ferocity; and their innovation stalled completely. When there’s a monopoly, Jefferson said, there’s no incentive to act well, or to improve. Shipbuilding techniques plateaued, navigation science stagnated, and the evolution of financing stalled.

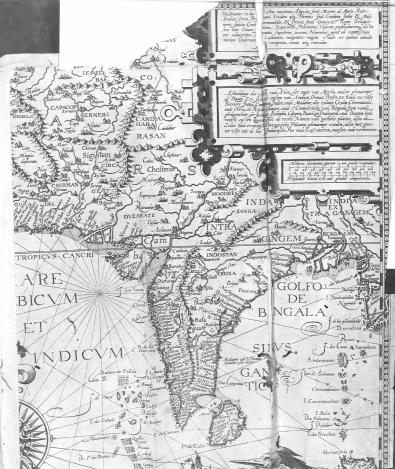

Linschoten’s map of India.

During that time, our hero, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, was working as a secretary for the Portuguese archbishop in Goa, India. In that capacity, he traveled all over the world. Somewhere along the way, he got his hands on the Portuguese maps, and he copied them. Then he returned to Holland. It took him a while — he was attacked by pirates and stranded in the Azores for two years — but by the time he got home he had written down all the information he’d gleaned (or stole) from the Portuguese.

Then he did something unusual: Instead of using the information himself, or selling it to a Dutch merchant house, he published it. This was after the invention of the printing press, but before the invention of copyright, so the maps multiplied freely. And this publication triggered a cascade of world-changing events.

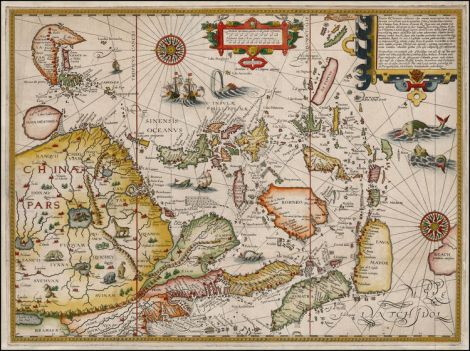

One of Linschoten’s maps. North is oriented left.

Linschoten published the maps in 1596. The British East India Company started in 1600; the Dutch East India Company was founded in 1602. The Dutch East India Company also represented an innovation in financing: It was the first joint stock company, and its formation gave rise to trade in options and derivatives. Once the maps were available and the Iberian monopoly was broken, new ideas flowered, and new investment flowed.

Now we have a similar situation, Jefferson said. There is a tremendous opportunity — not in mapping Asia and the Americas, but in mapping the patent system and all of its related knowledge. There’s currently a “clergy” (Jefferson’s term) of patent experts, who help big companies navigate the patent system for big fees. It simply costs too much for small inventors to see what’s already out there, “or what reefs and shoals to avoid,” Jefferson said.

The really crazy thing, Jefferson said, is that anyone can look up patents and grab recipes for creating technologies. This is especially true of the people who need innovation most, because patents don’t apply in most developing countries. Patents can only stop use of an invention in the country in which they’re granted. An enterprising Ugandan company could look up the instructions for Monsanto’s seeds in the patent literature, and build them tomorrow, without breaking the law, Jefferson said. The innovators and entrepreneurs are out there, he said — they just need the maps to show investors that the technology exists and their plans are legal and feasible. So he and his team created Lens.org, which works as a cartography tool for navigating patents and, ambitiously, all human innovation.

The Linschoten story sounded too good to be true. But when I looked it up, it checked out. The monopoly, the pirates, the theft of intellectual property, it all actually happened. (Here are some selections translated into English — there’s much more to his story.) Historians even agree that Linschoten’s maps were instrumental in breaking the Iberian hegemony.

Linschoten’s first book.

I don’t know if Jefferson is really a latter-day Linschoten, but I do think this analogy is useful for thinking about GMOs. We live in a time where agricultural innovation is done primarily by a small handful of companies that invested heavily in research and development early on. And innovation is stagnant: We see lots of variations on the Bt toxin, all kinds of recombination of a few other transgenic traits, and not much else. The investment dollar follows the proven moneymakers. There’s little incentive for truly creative thinking about the problem of agriculture.

Of course, the comparison extends beyond GMOs: Plenty of agricultural technologies are patented. GMOs are just the most obvious target; they are often used to represent the whole mess. As Jack Kloppenburg Jr. shows in First the Seed, for most of history, seeds defied the rules of capitalism as Marx defined them. Capitalism depends on separating the consumer from the means of production. But if you are a capitalist in the business of selling seeds you have a problem: A seed contains its own means of production. You plant a seed and, instead of using itself up, it produces … a lot more seeds.

So for most of history, farmers shared seeds, and innovators got prestige, but not much money. That changed with the introduction of hybrid seeds: Hybrids don’t reproduce their superior traits in subsequent generations. For the first time there was a powerful, inarguable, reason for farmers to stop saving seeds. GM technology completed this transformation of seeds into a commodity. Few modern farmers in the U.S. control their means of production anymore; they rely on seed companies and plant breeders to take care of that for them.

There’s nothing wrong with this division of labor, except that it means that fewer people are tinkering. We’ve centralized the responsibility for agricultural innovation among a few engineers, even fewer investors, and just a handful of corporations.

The impenetrability of the patent system gives these firms a virtual monopoly. As Kloppenburg puts it, “In what is frequently likened to a nineteenth-century style ‘land grab,’ vast tracts of the genescape … are being appropriated via patents.” There are few routes of passage left, and any innovator who wants to traverse this landscape has to contend with overlapping property rights and the constant threat of attack by hungry lawyers. The big companies have the same problems, of course, but they have the money to hire the intellectual-property clergy to make deals. Now the big players have cross-licensing agreements. Smaller inventors can’t even afford to sit down at the bargaining table.

The result is an Iberian peninsula of farming technology. It has tremendous power, but no incentive to try crazy new things. It stifles innovation and is unresponsive to the needs of its consumers.

Jefferson wants to disrupt this system the capitalist’s way, with newer, wilder ideas. Kloppenburg argues for — and has helped start — an open-source system for plant scientists. It will take someone smarter than me to figure out the best answer to this problem. My point, in recounting this story, is simply to note that this is a way that today’s handful of market-dominating GM seeds are linked to a real problem. They’ve led to a consolidation of power, and an increasingly confused patchwork of patents. They’re an integral part of a sclerotic and narrowly focused system.

As Jefferson puts it, “The real problem is the inertial forces of big business driving out strategies and models that would create a vigorous, decentralized and democratized innovation capability.”

If there’s something that can be done about that, it’s worth giving up lunch and talking till we’re blue in the face to make it happen.