There was a fistfight over corndogs at my first Meatpaper party. We were crowded up against the kitchen counter at Camino, a restaurant in Oakland, Calif., with brick walls and a big open fireplace. They were cooking a whole pig in that fireplace, dispensing plates of flesh to the crowd on the other side of the counter. To get some pig you had to push your way into this mosh pit and lunge for a platter when it emerged. You’d come away with a handful of something — though not necessarily something readily identifiable: Chitlins? Head cheese?

I’ll admit that I didn’t see the fistfight — I heard there were punches thrown, but perhaps it was just a scuffle. The story could have been embellished as it spread around the room. But it wouldn’t surprise me if somebody lashed out when denied homemade corndogs. I retreated from my excursion to the front of the restaurant, coddling a handful of offal and breathing hard.

For years, the editors at Meatpaper (I was one) considered writing about this high-testosterone meat frenzy, but we never did. It recurred at many of our parties. Meatpaper was a tiny, beautiful magazine. It was started by two former vegetarians, Amy Standen and Sasha Wizansky, with conflicting feelings about meat. It just published its 20th, and last, issue. The parties were the yin to the magazine’s yang. The magazine was poor, primarily female, and sensitively nuanced. The parties were sold out, joyfully macho, and boisterous to the point of anarchy.

We liked to say we were documenting the “fleischgeist,” the spirit of the meat (a play on zeitgeist, the spirit of the times), but maybe the rise and fall of the magazine itself — the history as opposed to the content — is the most reliable documentation. You can’t actually see trends, just the things they affect — just as you can’t see the wind until it picks up a leaf. By watching what happened to Meatpaper you could see the movement of otherwise invisible currents in meat culture.

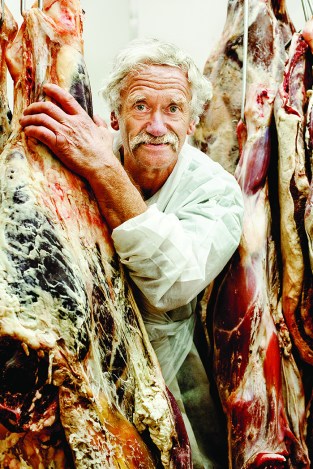

“I think all of us were surprised at how posh and decadent and fin de siecle meat culture became in the Bay Area in the years after Meatpaper started,” wrote Heather Smith, another editor, in an email. She’d been to Cochon 555 — a pork party that started up shortly after Meatpaper and has grown into an institution — at the Fairmont, a San Francisco hotel. “It was insane — all those pig carcasses and severed heads reflected endlessly in the Versailles-style mirrors of the Fairmont. Waiters circulating with brains canapes on silver trays. It was unsettling for me at least to see how the people who actually raised the pigs that made the Bay Area’s charcuterie renaissance possible, like Liz and Dan of Clark Summit Farms, didn’t receive nearly the compensation or the media attention that the rockstar butchers did. And there was a not inconsiderable amount of bro-ishness, like the butcher at one event (not ours) who fake humped a pig carcass like Miley Cyrus on a backup dancer.”

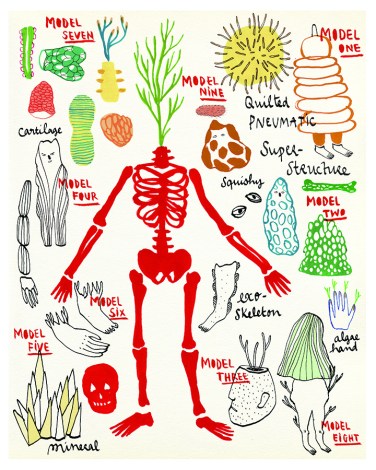

Elizabeth ZechelMeatpaper illustration.

Blood! Death! Pleasure! These are the imperatives of the coliseum, not the hearth. But the gladiatorial approach brings in the crowds and opens wallets. The food that gets noticed these days tends to be extreme — whether it’s of the Double-Bypass Burger ilk, or humped pork. Chefs have to capture the attention of young, moneyed tech workers. And those diners are talking too loudly, drinking too much, and moving too quickly to actually taste their food unless it kicks them in the mouth.

This surge of meat mania may have buoyed Meatpaper, but the magazine’s sensibility was utterly opposed to it. And when I say “the magazine,” I really mean Sasha Wizansky, who did much of the work and took all the responsibility for getting the magazine out.

Irreverent is an adjective that’s often used to describe magazines. Meatpaper wasn’t irreverent. If anything, its tone was reverent — cheeky sometimes, and often whimsical, but always respectful. Meat is serious business. Meatpaper was made for people willing to slow down enough to appreciate the humble subtleties of food, rather than only noticing the food that grabbed their attention.

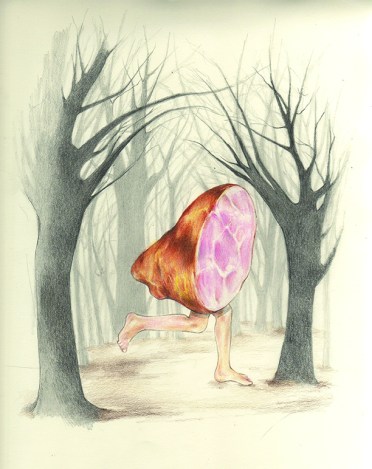

Kathryn MacnaughtonIllustration from Sandwich, a single-issue magazine that went out with Meatpaper.

There may not be many of those people, or they may not be the ones with the loudest voices and the most power, but they do exist. Subscribers wrote little love notes to Meatpaper. Far more artists submitted smart, compelling work (for free!) than the magazine could use. Editors at Harper’s Magazine picked up and reprinted pieces. The Walker Art Center and Cooper-Hewitt put the magazine in an exhibition. It won a bunch of awards.

I’d like to think that someday those 20 issues of Meatpaper will be collector’s items. If that ever happens it will mean we’ve moved away — at least slightly — from this culture of fetishizing food, and instead begun to actually taste it.

If I can enjoy the taste of food, rather than the spectacle surrounding it, it means I’m a lot closer to seeing and valuing the people, and creatures, that made it. If we want a sustainable food system, we’ve got to start seeing and appreciating everyone — and everything — involved in creating it. And we’ve got to see them for what they are, rather than seeing only the mythology.

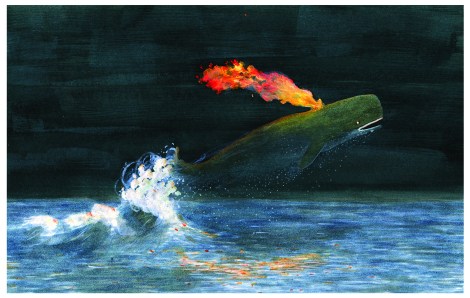

by Jessica NielloMeatpaper illustration

The final Meatpaper magazine party was more sedate than that first one I attended. A tall scruffy man — wearing a red flannel shirt, thick glasses, and a trucker’s hat — bellowed out one sea shanty after another into the chattering crowd. One of his hands grasped the neck of a beer bottle; the other rested on the sleeping baby slung over his shoulder. Two other singers, a pretty blond woman with an accordion and a short fellow with vigorous iron-grey hair and beard, accompanied him.

“You know who that is, right?” asked Sasha. I shook my head. “That’s Kirk Lombard.”

In a recent issue (the Fishue) I’d edited something Lombard had written about catching smelt. The piece had made the case for fishing by describing how miserable it was to go fishing. I’d found it funny and moving. The partiers stopped their conversations long enough to listen to the song, and applaud. There was no shoving. The baby slept on. This, I thought, was progress in the right direction.

Yutaka HouletteIllustration from Meatpaper.