ShutterstockNo actual farmers were harmed in the taking of this stock photography.

Biotech crops, which represent almost all the corn, soy, and cotton grown in the U.S., have finally met their match. And it’s not (only) the millions of consumers demanding labels on food that contains genetically modified crops, or GMOs. As NPR reports, biotech’s super-nemesis is legions of weeds and bugs that have grown immune to the herbicides and pesticides that many of these crops require.

Generally speaking, GMO crops fall into two categories: Some are designed to be resistant to pesticides like Roundup, Monsanto’s all-purpose weed killer. This allows farmers to douse fields with Roundup, killing everything but the corn, soy, or cotton (most commonly) that they’re trying to grow. Other GMO crops actually exude chemicals such as Bt, a “natural” pesticide that kills many of the most damaging bugs.

The technology may or may not be deserving of the World Food Prize but it’s certainly been a huge business success. At least it has been — until the weeds and bugs that these crops are engineered to withstand find ways to kill the crops anyway.

We at Grist have been tracking the scourge of superweeds and superbugs for years now. And whatever the merits of a debate over pros and cons of biotech, the facts on the ground suggest the underdogspests are winning.

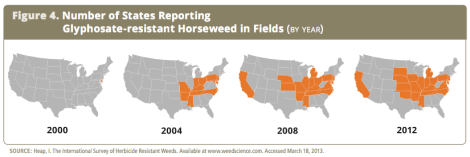

It’s fair to say that the story is no longer about the rise of superweeds and superbugs. It’s now about their dominance. As this chart from a recent Food and Water Watch report shows, in 2000 — only a few years after the introduction of GMO crops — superweeds were barely a blip on farmers’ radar. But now the picture is different:

The same is true for superbugs — specifically pests like the corn rootworm — which have become increasingly resistant to the forms of Bt pesticide that are exuded by genetically modified corn, soy, and cotton. Scientists are still exploring the extent of the problem and whether or not the resistance is due to the GMO crops themselves or simply the result of random variation among the insects in question. Whatever the cause, farmers are the ones who have to figure out how to handle the increased threat to their livelihood.

In an interview with the agriculture trade publication Brownfield, agronomist and ag consultant Todd Claussen admitted that, at least in Iowa, they’re definitely seeing rootworm damage on GMO Bt corn, which is supposed to resist the bug. That’s bad enough, but it’s not the whole story. Claussen goes on to explain that rootworms in Iowa this year are 40 to 50 times worse than normal. And in large part that’s because of recent weather conditions: Drought, followed by heavy, early rains, has created perfect conditions for rootworm growth.

Nature is showing a resilience, and an ability to adapt to changing circumstances, that biotech simply doesn’t appear to have. The near-term result, as Food and Water Watch points out in a new report on the subject, is a huge boon to pesticide companies — many of which also market the GMO seeds — since farmers are turning to more and more toxic pesticides in order to control the dynamic duo of these bugs and weeds.

For example, farmers are now spreading 10 times more of the herbicide Roundup on corn, soy, and cotton than they were 15 years ago. While some of that increase results from the widespread adoption of Roundup Ready crops, some of it is because, to combat superweeds, farmers are increasing the pounds of Roundup they apply per acre.

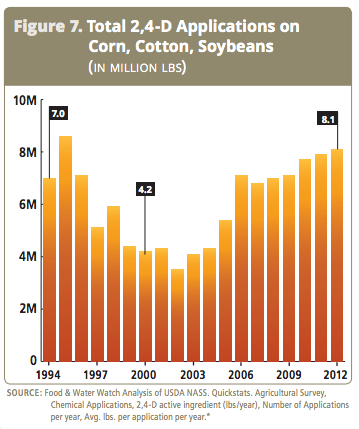

An even better indicator of the increase in pesticide use is 2,4-D, a highly toxic pesticide that was an ingredient in Agent Orange. Many farmers abandoned the chemical because of its toxicity as well as its tendency to drift onto neighboring fields, but 2,4-D use has crept back up because farmers are finding that they have no choice — the weeds are winning. As you can see from this chart from the Food and Water Watch report, 2,4-D use has now returned to the level it achieved before the widespread adoption of Roundup Ready GMO seeds:

The chemical has recently become doubly controversial because Dow AgroSciences submitted a GMO seed to the U.S. Department of Agriculture that resists 2,4-D’s effects. Thus, the cycle could start all over again: Weeds are outsmarting our Roundup Ready crops? We’ll just use Agent Orange-Ready crops instead — that is, until the weeds find a way around those, too.

The USDA has delayed approving the 2,4-D seeds in the face of strong objections from consumer safety advocates and farmers concerned about water quality and pesticide drift. But it’s only a matter of time before Dow’s product gains regulatory approval, along with several other GMO seeds that are resistant to other highly toxic pesticides like dicamba and isoxaflutole.

If all these seeds come to market, pesticide use on American farmland will skyrocket. And with it will come an increase in water contamination, human exposure, and higher chemical residues in food.

But there’s an alternative to better living through chemistry: Farmers can simply stop planting corn year after year and learn to love oats and alfalfa. As one crop consultant told NPR, the simplest, cheapest, safest solution is just to switch to another crop for a bit. Rotating crops, i.e. growing different crops in sequence on the same plot of land, is an old technique for foiling pests. Very often, a bug that eats one crop won’t eat a different one. Corn rootworm will starve in a field of oats. So switching up crops will keep farmers one step ahead.

Rotations are, however, more complicated. GMO seeds plus cheap synthetic fertilizer plus high market prices opened the door to what’s called “continuous corn” — growing corn season after season on the same land — which made commodity farming simpler than ever.

Recent research into crop rotations, however, indicated that farmers won’t necessarily lose money since they’ll be spending a lot less on high-priced GMO seeds, chemicals, and even fertilizer. Even the USDA gets this. The agency has started to promote the adoption of what it calls “multi-cropping” for improved pest management and climate resilience. The problem is that the agency is also encouraging biotech companies to keep the herbicide-tolerant seeds coming.

But nature has shown its ability to outwit chemists time and time again. Perhaps we would be wise to start working with nature, rather than jumping back in for another round in a fight we seem to be losing.