This story is a part of a series about local food systems.

The roomful of environmental-science students at Fresno State didn’t exactly seem proud of their town. There were dismissive titters when political science professor Mark Somma suggested that Fresno, Calif., could be a place that drew people from around the world, seeking a higher quality of life.

The laughter didn’t slow Somma. Think of Fresno’s resources, he told them. It’s surrounded by some of the richest farmland in the world. It has a tremendous cultural diversity. It has views of the Sierra Nevada, and a river of Sierra snowmelt running along its northern border. And yet Fresno frequently pops up on lists of the worst cities. Every year it sprawls farther into the farmland, creating mile after repeating mile of identical strip malls and stoplights.

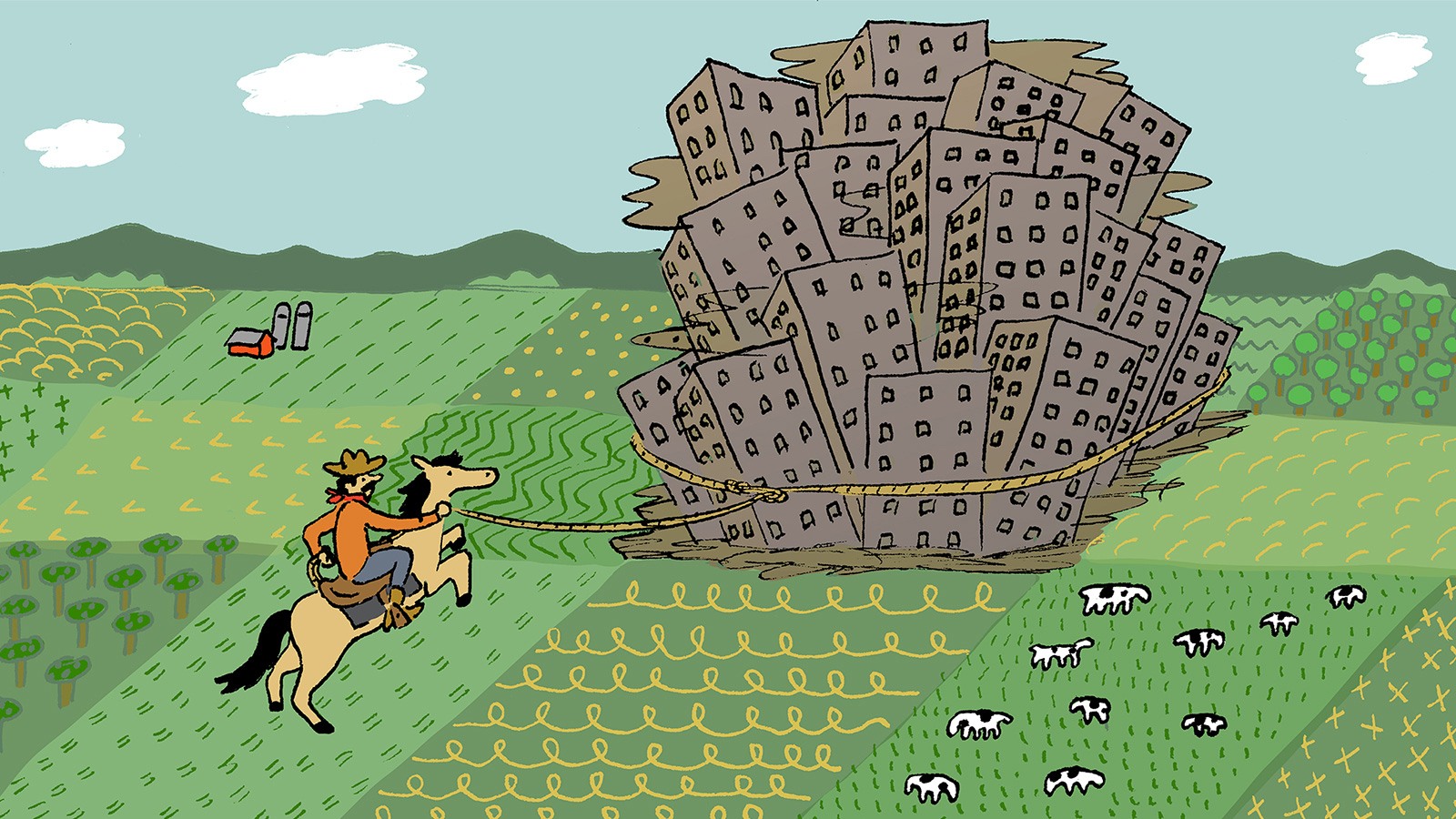

There used to be another city a lot like Fresno, Somma told the room. It too was an industrial, agricultural town — unlovely, uncool, unknown. But this town decided to embrace, celebrate, and protect agriculture. The city leaders drew a circle around their perimeter and promised not to develop farmland beyond that line. This focused development inward. Instead of growing out and hollowing out, the city grew up. Food culture, buoyed by the nearby farms, began booming. Locals started taking pride in their coffee, their beer, their meat, their dairy, their fruits and berries. Outsiders began to hear about this proud, gritty town that had pulled itself up by its bootstraps, and people started moving there.

The name of that town? Portland.

I’d always thought of the competition for land as a contest between rural and urban interests. Farmland and the rural culture inexorably makes way for suburbs and business parks. But what if it was possible to turn this competition into cooperation, to have cities that enriched farms and vice versa? Had Portland figured this out? If so, it was worth noting. I’d written about how, for all of its virtue and value, urban ag will not feed our cities — we’ll need farmers and farmland for that.

And then there was Somma’s suggestion that preserving farmland on the outskirts of a city could actually spark an urban renaissance. Could that really be true?

Of course there’s a little more to the story, said Craig Beebe, communications director for 1,000 Friends of Oregon, a pro-planning group. Back in 1973, an alliance of farmers, cities, and timber interests passed a law to protect farm and forest land. Signed by Republican Gov. Tom McCall, the law drew a circle around every city in the state, restraining sprawl outside those lines while making it easier for developers to build inside.

But in Portland specifically, other things were afoot. Residents organized to stop two freeways, and then found a way to divert the resources behind the freeway efforts to a light-rail system and developing the waterfront. “There was this feeling that, we are not just going to try to defeat things,” Beebe said. “We are going to reapply that energy toward building better things.”

So protecting farmland wasn’t the single factor in Stumptown’s rebirth, but it was a key element in making Portland what it is today.

“It’s been an essential tool to pull things together,” said Ethan Seltzer, a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. Because the metropolitan area hasn’t spread like spilt milk, it’s still fairly easy to travel around the city on foot or by bike. (Portland has also poured a ton of money into bike lanes, and public transportation, which also helps.) That compaction also makes city services — roads, sewer lines, water pipes — more efficient. Extending those services to sprawling developments is expensive.

“You don’t have to build services to all hell and gone,” Seltzer said. And that’s allowed the city to invest in other things.

Preserving farmland has helped define the city in less quantifiable ways too. Businesses from small tech startups to big corporations like Nike and Intel cite Portland’s connection to the surrounding land in their employee recruitment. Food from nearby farms has contributed to a booming restaurant scene. “Around here we have family rituals around the ripening of certain crops and cutting Christmas trees,” Seltzer said.

That’s not to say everyone likes the rules protecting farmland.

There are plenty of people in Oregon, even some of the law’s original supporters, who say the regulations are too baroque and restrictive. One of the people who dislikes the rules is John Charles, president and CEO of the Cascade Policy Institute, a libertarian think tank (surprise, a libertarian who dislikes rules!). Not only does he say the urban growth boundary has failed to make Portland a better place (he hates the way the city has changed), Charles questions the notion that we need to protect farmland at all: “There is no shortage of agricultural land or agricultural commodities and there never will be, as long as we allow markets to function.”

But, I said, isn’t this a place where you have market failure? It’s easy to build houses on cheap farmland, but it’s a one-way ratchet, it’s hard to remove the concrete.

“You don’t need farmland for crops,” Charles said. “You can grow them hydroponically. Who needs soil?”

Who indeed? Perhaps those whose faith in the free market is less than their faith in the scientific consensus. The mainstream forecasts suggest that we’re going to need all the good soil we can spare as the world population nears 10 billion, even counting hydroponics.

We’re also going to need more farmers to work that land more intensively — something we’re beginning to see in the Willamette Valley, south of Portland, where a retinue of young farmers produce food for CSAs, restaurants, and markets, rather than the usual commodity crops. “It gives farmers a different option,” said Jim Johnson, land use specialist at the Oregon Department of Agriculture. “It’s mainly small farmers, but it allows them to get going, and they can always expand.”

Roughly 70 percent of Oregon’s agricultural economy is based in the Willamette Valley, Johnson said, and 75 percent of the population is there. Farmers and city people can live, even thrive, together.

That’s not to say that Portland exemplifies a fully formed regional food system. Hardly. There’s local food going to boutique eateries, sure, but roughly 80 percent of Oregon’s agricultural production leaves the state, Johnson told me.

But in terms of simply preserving farmland, it’s clear that the program is working. It’s strange to drive out of Portland: Instead of crawling in traffic through suburbia, the city just stops and you are suddenly in rolling fields. Johnson protests when I suggest that the rules are overly bureaucratic. “If you want to develop something and you aren’t allowed to, you are going to say the process is broken,” he said. In fact, Johnson said, perhaps the rules should be stricter.

The state’s planning law doesn’t completely stop the development of farmland, David Dillon, executive vice president of the Oregon Farm Bureau, told me, “It just provides an orderly process to do that.”

The cities may periodically expand their boundaries, but still, Oregon has lost far less agricultural land than its neighboring states of Washington, California, and Idaho. And there has been a steady growth of the agricultural economy in Oregon since the 1970s, Johnson said.

Any idea that unites (generally conservative) farm advocates with (generally liberal) smart growth advocates seems like a winner. But Charles points out that other states have tried to adopt urban growth boundaries and failed. “If you’re leading a parade for 41 years and no one is in your parade,” he said, “you might have to rethink your assumptions.”

Just about everyone I talked to thought it would be harder to pass Oregon’s land planning law today. The U.S. has simply become too partisan and individualistic. It’s hard to make an argument in today’s America that we should sacrifice individual freedoms for the common wealth.

There are alternative tools in the toolbox for protecting farmland. Cities can institute agricultural zoning. Some communities are working on markets that allow developers to build higher and bigger if they also buy up and protect open land outside the city. Agricultural land trusts make use of conservation easements — a legal tool that limits the development of one piece of property at a time — or just buy up parcels. Then there’s the consumer approach: Buy-local campaigns, CSAs, and similar efforts help keep local farmers in business — and their land from becoming the next subdivision.

All of those things require buy-in from people who live in the city, however. And they have to believe that there’s something in it for them.

Which brings us back to Somma’s idea. Could farmland preservation revive a city? Basically, Somma was right: The urban growth boundary has been a key part of making Portland the city it is today. But Oregon’s planning law only came about because a lot of energetic people wanted some communal guidance of the way the state’s cities and countryside developed. In other words, if Fresno wanted to replicate Portland’s trajectory, it would have to start with a critical mass of its own homegrown smart-growth advocates — and get them working before they all move to Portland.