On Tuesday, Pennsylvania voters will decide the future of abortion in this state.

In the aftermath of Dobbs v. Jackson’s Women Health Organization, the Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade’s constitutional right to abortion and made abortion rights the purview of state government, 13 states have banned the procedure altogether, most with very limited exceptions. In Pennsylvania, the Republican-controlled legislature has been preparing to enact an abortion ban for years. Democratic Governor Tom Wolf has promised to veto such a ban as long as he remains in office.

But Wolf’s second term is drawing to a close, and the availability of safe, legal abortion in Pennsylvania is essentially dependent on which candidate succeeds him: sitting state Attorney General Josh Shapiro or ultra-conservative Christian nationalist Doug Mastriano. Shapiro has promised to protect access to abortion, whereas Mastriano intends to severely restrict it. If Mastriano prevails and Republicans retain their majorities in the state House and Senate, Pennsylvanians’ right to terminate pregnancies would likely come to an end.

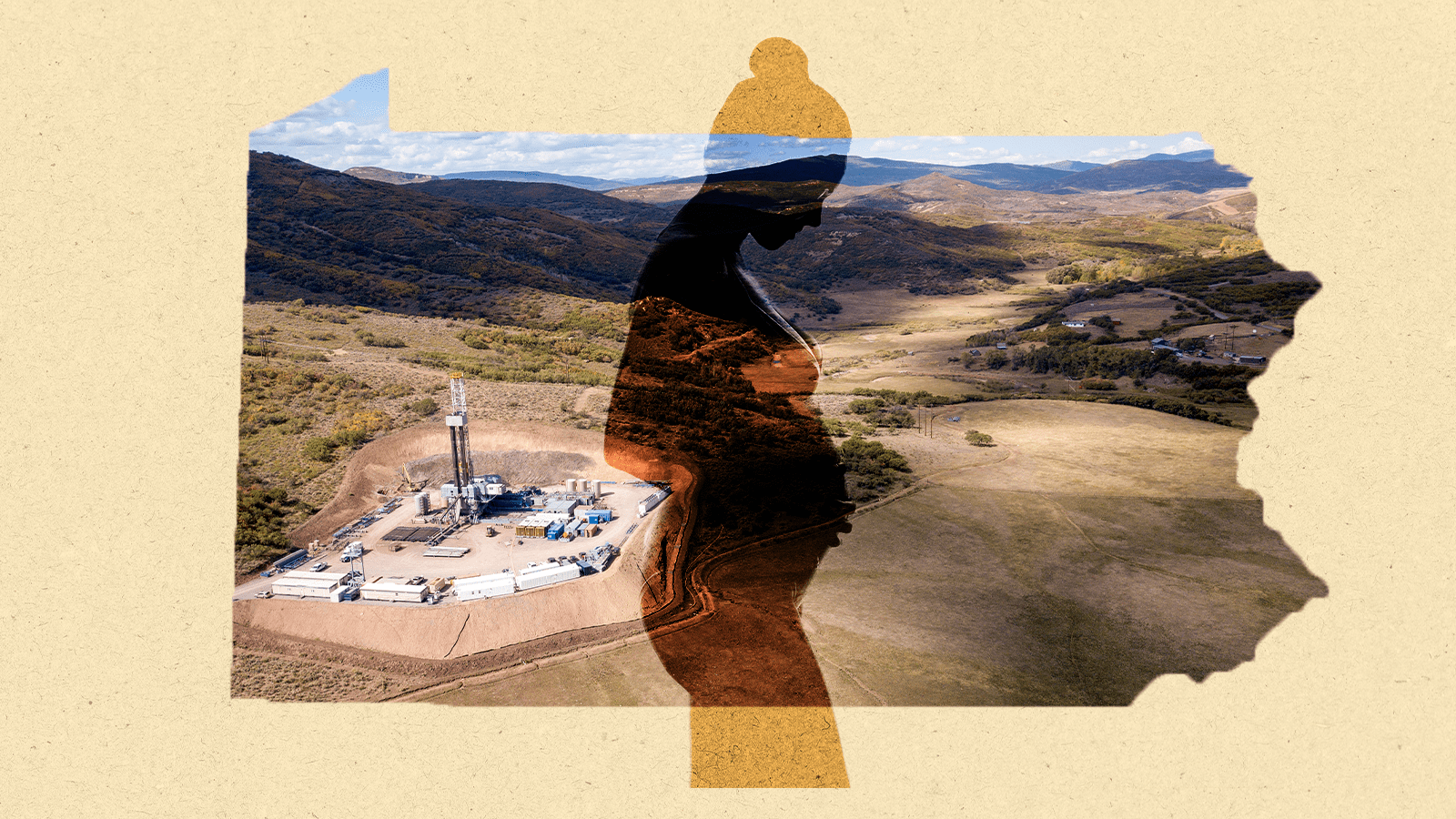

In southwestern Pennsylvania, this battle for reproductive rights takes place against a disturbing backdrop. Over the past 15 years, shale gas development has proliferated across the region, with thousands of unconventional wells — also known as fracked wells — drilled since 2007. And due to widespread fracking being a relatively new practice and the oil and gas industry’s efforts to conceal and downplay the toxicity of chemicals used in it, Pennsylvanians are just beginning to understand the potential health impacts of living, becoming pregnant, and raising a family in the second-highest natural gas-producing state in the nation. For these Pennsylvanians, a ban on abortion would just be one more way in which their health has been wrested out of their control.

“I feel like if you’re going to say, ‘life is so precious,’ and then take away the rights of women, I think you should think about what’s happening around the people that are trying to have children,” says Gillian Graber, a mother in Westmoreland County and executive director of the fracking awareness organization Protect Penn-Trafford.

Graber and her family participated in a landmark investigation conducted by Environmental Health News in 2019 that found high levels of chemicals used in the fracking process in the bodies of people living near well pads. “We’re going to have several generations of people that may see really dramatic consequences to something that they had no part in planning, no part in allowing, no say in whether it happened in their community.”

There is a fast-growing body of literature on the dangers that oil and gas development can pose to maternal and prenatal health. Higher rates of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, conditions in which a person develops sometimes life-threatening high blood pressure during pregnancy, have been found in pregnant people who live in close proximity to oil and gas wells. Babies born to families that live near wells are also more likely to be born preterm and with lower birth weights, conditions that put them more at risk for other health issues throughout childhood. They are also more at risk of congenital heart defects.

Makenzie White, a licensed social worker and public health manager with the public health nonprofit Environmental Health Project,* says the public health principle of “biological plausibility” helps explain why it should not be “shocking” that living close to fracking operations would be associated with negative health impacts for pregnant people, infants, and children. For example, benzene is a known carcinogen and endocrine disruptor, and it’s also a hydrocarbon that has been observed to be released in the fracking process. Many forms of air pollution have documented negative effects on maternal and prenatal health — including increased risk of miscarriage — and fracking sites have measurably worse air quality than the areas around them.

“Part of the concern with pregnant individuals and children is that we already know from research on other topics that it’s a vulnerable time to be impacted from any type of pollution,” she says. “There’s also been a lot of research about these different chemicals and toxins impacting fertility in general, which is very concerning, and would indicate that we would need more supportive healthcare in order to take care of our residents and better protect them.”

There is significant evidence that people who live near fracking sites suffer higher rates of complications during pregnancy. And if abortion is made illegal, those complications will become much more dangerous. Abortion can be medically required in the case of severe preeclampsia, to manage a miscarriage, or in response to other serious problems to save the pregnant person’s life.

“Imagine you’re someone who already has a high risk, and you live near a polluting site that could increase your risk, and it’s out of your control,” says Laura Dagley, a nurse who works in public health education for Physicians for Social Responsibility. “You’re afraid for your life, the life of your baby, and if you’re in a situation where it’s no longer medically recommended for you to continue with the pregnancy — and then there’s no access to abortion. It’s scary for me to consider that Pennsylvania as a state would considering putting communities’ health at risk, either in unchecked pollution by the oil and gas industry, and taking away access to safe abortions.”

Dagley has made it part of her life’s work to inform Pennsylvanians about the risks of living near fracking sites. She recently spoke to residents of Washington County in southwestern Pennsylvania at a community event about an ongoing study conducted by the University of Pittsburgh into a suspected connection between fracking waste and an unusually high incidence of a rare bone cancer called Ewing’s sarcoma among children and adolescents in this region. She says it was attended by a number of parents of young children who had heard vague connections made between fracking and health problems in the community and were curious to learn more.

At a park pavilion in Canonsburg, about a hundred residents took in presentations on the observed higher rates of childhood cancers, asthma, low birth weights, and preterm births in regions where oil and gas extraction is prevalent. Erica Jackson, a community outreach manager for the FracTracker Alliance, told the crowd that “some of the strongest evidence of fracking health impacts is on infants.”

Dagley noticed some grave expressions in the crowd as the presenters spoke. “There are people who are considering whether or not they want to have children, if they’re putting them at risk, but I think there are many people who already are pregnant or already have kids who feel a lot of guilt,” says Dagley. “Even though it’s not their fault, it’s very much the fault of the industry and people who are refusing to regulate and stop this industry from doing harm.”

“It’s a hard part of being the person who’s there to talk about the research and health impacts, I can just see it on people’s faces, they’re like, ‘Oh great, I didn’t know this is happening, and now my child is sick, or now I am pregnant. What do I do?’ It’s not so easy to pick up and move. It’s very hard to see people try and process that.”

There’s also an incentive not to process it — to not have to face change or challenge the status quo of the community. Janice Blanock, a Washington County resident whose son Luke died from Ewing’s sarcoma in 2016 at the age of 19, says that many members of her community aren’t interested in understanding the potential health impacts of oil and gas development.

“I think people are kind of afraid — like, if I get too involved I’ll know too much, and I won’t be able to support jobs,” she says. “And once you know, you can’t take it back, you can’t unknow what you learned.”

But what happens when you begin to understand the risks lingering in your air and water? Every woman I spoke with for this story, all of whom are mothers or grandmothers themselves, said the same thing: that knowing about the risks that fracking pollution poses to a fetus or to a child is unlikely to sway a person who wants to have a baby from having one. Instead, what they do is adapt to the circumstances they’ve been handed.

Lois Bower-Bjornson, a dancer and field organizer with the Clean Air Council in Washington County, was raised in Western Pennsylvania and returned in 2004 to raise children in a more rural setting, full of woods to roam and creeks to play in. “Prior to moving back here, the pollution aspect didn’t enter into my head,” she said, as the coal and steel industries that dominated the region throughout the 20th century had largely died off. But when oil and gas companies began drilling unconventional wells around her home “like the Wild West,” suddenly her children were sick all the time.

“And then there it is, it happens and you’re there, and you do the best that you can with what you have,” she says. “We have air monitors, I asked for a water filtration system two Christmases ago, and my kids are educated to know, ‘you can’t go outside right now, the air is terrible.’ You become kind of an expert on what to do and when to do it with your children, and what to do when you do live in a polluted community.”

Fossil fuel interests have been deeply entrenched in Pennsylvania politics since the first well was drilled in Titusville in 1859. And unlike abortion, positions on fracking are not cleanly divided down party lines. Many Democrats in the state government today — including Governor Wolf and Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman, currently a candidate for U.S. Senate — have consistently supported fracking in Pennsylvania as an economic boon, and oil and gas companies have enjoyed significant tax breaks in the state. An exception can be found in the U.S. House of Representatives candidate Summer Lee, who seeks to represent the district containing parts of Allegheny and Westmoreland counties in the southwestern part of the state, and has been vocally opposed to fracking and outspoken about its health consequences throughout her career.

There is something to be said for loving one’s home so much you want to heal its many wounds. Southwestern Pennsylvania is riddled with centuries-old scars of many, many different forms of industrial exploitation. But it is also filled with families who have made its hills and valleys their home for generations, and want to see their grandchildren and great-grandchildren make it theirs as well. And there you can find a contingent that campaigns and organizes and votes, in hopes that the slow pace of political change will catch up to the more reckless stride of fossil fuel development.

Joining that contingent this year are voters who have been freshly mobilized by Mastriano’s threats to abortion rights in the state. Bower-Bjornson, for example, says that she has conservative, Trump-supporting family members who will be voting for Democrats on November 8 because they fear for the health of their daughters should abortion become illegal in Pennsylvania.

In the meantime, what do you do if you want to start a family in western Pennsylvania — or any oil and gas producing region — or if you already have one? The good news is that most negative maternal and prenatal health impacts associated with fracking are observed only in people who live quite close to a well, within about a half-mile radius; the bad news is that there are hundreds of new active wells every year, and residents often get little warning about their installation. Just a few years ago, a new well pad was installed very close to the home of Janice Blanock, the woman whose teenage son died from Ewing’s sarcoma. There was a town meeting to inform the community about the new well, but many local residents were in favor of it because of the jobs they believed it would provide.

But Blanock has no plans to move, and no desire to. “I still love it, it’s home, but I worry now where I didn’t before, and I’m aware of more,” she says. “I would say if you’re going to have children, you definitely want to look into where you raise them. And I don’t know if this is the safest place for you to do that, sadly.”

*Correction: This story originally misidentified Environmental Health Project and Makenzie White’s professional background.

This story has also been updated to clarify Lois Bower-Bjornson’s job title and the nature of the evidence that people who live near fracking sites suffer higher rates of complications during pregnancy.